July 24, 2024

Ms. Amy Chen

Community Development Director

City of East Palo Alto

Via email to: rbd@cityofepa.org, achen@cityofepa.org

Cc: troy@raimiassociates.com

Re: Public Comment on Ravenswood Business District/4 Corners Specific Plan Update

Dear Ms. Chen,

The Sierra Club Loma Prieta Chapter’s Bay Alive Campaign, Citizens Committee to Complete the Refuge, Green Foothills, and Sequoia Audubon Society are pleased to provide these comments on the Draft Ravenswood Business District (RBD)/4 Corners Specific Plan Update (DSPU or Plan). Our organizations understand the interdependence of nature and people so work to enhance sea level rise resilience while protecting wetlands, open space, wildlife habitat, and other ecological and natural resources in the Bay Area. We collectively represent tens of thousands of members in and around East Palo Alto who care deeply about open space, nature, and community resilience.

We commend the diligent efforts of the City Council, City staff, and the consultant team in developing a thoughtful plan for the future development of the RBD/4 Corners area. We are particularly pleased that the DSPU reflects a strong commitment to conserving tidal marshes, tidal flats, and their vital habitats. The proposed inland levee alignment and shoreline transition zones preserve important opportunities for long-term resilience. We also applaud the DSPU’s innovative community benefits framework, which ties development entitlements directly to specific, community-identified priorities, increases financial transparency, and enables the City to comparatively evaluate proposed community benefits.

We remain concerned that Scenario 2, including more than 3.3 million square feet of new office/R&D space, will overwhelm East Palo Alto with impacts that irreversibly alter the character and resilience of the community. Nevertheless, we offer comments below to strengthen the efficacy of the Plan across all scenarios.

Many of the issues we raise do not fit neatly into a single chapter of the DSPU, so we have organized them into the following sections based on subject matter.

- Overarching concern about the reliance on the 100-foot BCDC band

- Protection of Wetlands

- Biological resources: Habitat Enhancement, Expansion and Protection

- Lighting

- Hazardous Materials

- Additional Comments by Chapter

Please note that as a jurisdiction that borders the Bay, East Palo Alto is required to submit a shoreline resilience plan by 2034 for approval by the Bay Conservation and Development Commission (BCDC). The City and this Specific Plan should recognize BCDC’s upcoming release of its Regional Shoreline Adaptation Plan (RSAP) expected, by State requirement, in December 2024. The RSAP will include minimum standards and criteria for sea level rise adaptation planning that must be met to secure approval for local resiliency plans. Jurisdictions with BCDC approved plans will receive priority consideration for State funds.

1. OVERARCHING CONCERN ABOUT RELIANCE ON THE 100-FOOT BCDC BAND

The DSPU’s shoreline strategy relies on the Bay Conservation and Development Commission’s (BCDC) shoreline jurisdiction, specifically the 100-foot BCDC band, to accommodate public access, Bay-facing amenities and aesthetics, bayland habitat protection, and the future SAFER Bay levee. However, due to variability in tide and topography, the BCDC band’s alignment fluctuates by location. In East Palo Alto, much of that 100-foot band lies offshore, encompassing tidal marsh and other wetlands.

In multiple locations, therefore, the desired facilities, including the SAFER levee, will not fit within the BCDC band without encroaching on the Bay. To avoid Bay fill, the Joint Powers Authority might forgo the larger levee size recommended for the SAFER project in favor of less flexible, less sustainable, and more ecologically damaging flood walls. Additionally, new developments, including buildings as much as eight stories, could be much closer to Bay habitats than intended, potentially causing greater impacts. It could result in reduced setbacks, increased light and shadow effects, and possible narrowing or elimination of shoreline parks. These changes could harm wetland habitats and the species that rely on them, while also reducing public open space.

To address these concerns and ensure more consistent development standards and outcomes, we strongly recommend that the RBD SPU use a different reference point to define the desired 100-foot shoreline band for the Plan area. Instead of relying on the BCDC band, we recommend establishing an overlay zone that extends 100 feet or more inland from the edge of Waters of the United States closest to the shore, determined by obtaining a Jurisdictional Wetland Determination (JD)1 from the US Corps of Engineers (USACE). Waterfront developers with wetland property can be required to obtain a JD for Pre-application packets. Using a delineated landward edge of wetlands would provide a more stable Bay edge reference for shoreline setback and stepback measurements, reduce environmental impacts, and preserve natural wetland infrastructure that can serve as a vital adaptive complement to the SAFER levee.

2. PROTECTION OF WETLANDS

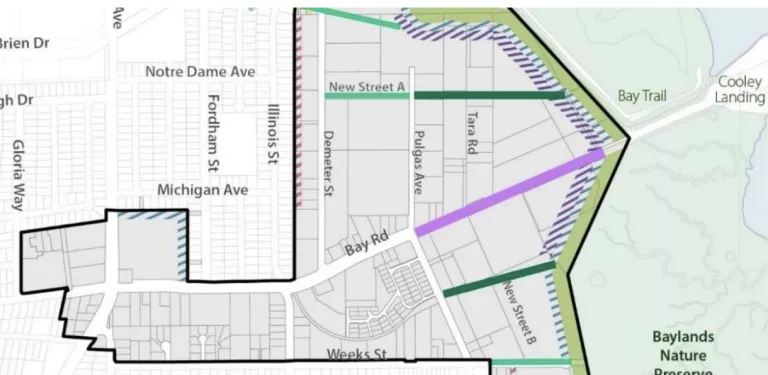

The DSPU includes significant strategies aimed at embracing Bay wetlands, such as a Waterfront Promenade, alignment of roadways as Bay view corridors, restoration requirements north of 391 Demeter, and spatial planning for the SAFER levee project to minimize impacts on existing wetlands. We appreciate these elements of the DSPU, reflecting the community’s strong appreciation for and relationship with Bay marshlands. Our comments in this section highlight some important clarifications to strengthen the DSPU’s approach to wetland protection.

The DSPU describes lands within and adjoining the wetlands in text and maps. Please change the descriptions of “Baylands Nature Preserve” to “Don Edwards San Francisco Bay National Wildlife Refuge” to reflect management authority held by the Refuge.

Lying southeast of Cooley Landing, most of the marshes from Bay Road to San Francisquito Creek are owned in fee-title by the City of Palo Alto. However, because the marshes are situated across city and county boundaries, Palo Alto lacked jurisdiction over the lands, limiting its ability to protect and conserve them. In 1994, Palo Alto signed a Cooperative Licensing Agreement with the United States Fish and Wildlife Service (USFWS)/Don Edwards San Francisco Bay National Wildlife Refuge (Refuge).2 Under that agreement the lands have been held in Federal jurisdiction, with the Refuge performing as land conservation manager within its authorities as a National Wildlife Refuge. Management plans for this area, known as the “Faber and Laumeister Tract,” are outlined in the Refuge’s Comprehensive Conservation Plan.3 All decisions regarding these lands are made solely by Refuge management.4 This includes any type of access into these marshlands.

Misrepresentation of management authority for these lands may cause City administration and adjoining landowners to incorrectly direct inquiries to the City of Palo Alto, rather than the Refuge. This would slow resolution of incidents such as accidents, homeless encampments or even toxic chemical spills, as well as impede planning procedures. For example, the DSPU Concept proposes a new pump station at the location of an existing stormwater outfall at Runnymede, which drains directly into Laumeister Marsh. The Refuge, not the City of Palo Alto, would be the partner working with East Palo Alto on such a project.

Recommendation: We recommend that all DSPU maps and text replace the label “Baylands Nature Preserve” with the “Don Edwards National Wildlife Refuge.” We also recommend that all text references referring to offshore marsh management name the Don Edwards SFBNWR in addition to the MidPeninsula Regional Open Space District. Contact should be to Refuge Management.5

As discussed above, multiple locations in East Palo Alto include wetlands within the BCDC band. In at least two cases, private developers are known to own Bay wetlands. Emerson Collective's project documents indicate that their property, identified generally in the DSPU as 391 Demeter, includes tidal marshes that lie within the BCDC band.6 Similarly, Harvest Properties' survey maps show their ownership of wetlands outboard of the Bay Trail, also within the BCDC band alignment.7

We did not find any mention of the wetlands owned by Harvest Properties in the DSPU. Wetland protection requirements, akin to those included for the 391 Demeter wetlands, should be applied to these privately-held wetlands. We do not have comparable information about other shoreline properties.

Recommendation: We reiterate the importance of Jurisdictional Delineation and Determination to establish a more definitive boundary between lands and waters within the Plan area. We recommend that the DSPU require all properties that include or border wetlands to provide preliminary jurisdictional determinations of those lands in the pre-application packet for any proposed development. Additionally, the DSPU’s wetland protection requirements should be applied to all privately-owned wetlands, and landowners should be encouraged to protect their wetlands, e.g. with Conservation Easements and agreements for ongoing, qualified conservation management.

We were very pleased to find that Section 7.3.4, Tidal Marshes, includes thoughtful and substantive guidelines for marsh protection, enhancement and ongoing conservation as well as important limitations on Bay fill. Please consider the following clarifications.

- Clarify Bay fill limitations. The only mentions of Bay fill in the DSPU appear in Section 7.3.2, Standard 12, pertaining to Waterfront Parks, Open Space, and Levee8 and in Section 7.3.4, Guideline 6, pertaining to Tidal Marshes.9 It appears that the intention is to disallow Bay fill except for these purposes and under the stated circumstances.

However, the absence of reference to Bay fill in the Land Use Chapter, may beg the question.

Recommendation: State explicitly in the Land Use Chapter that Bay fill is permissible only in the limited locations and circumstances described in the above cited Standard and Guideline and only when the action is necessary and unavoidable.

- Add “enhancement” to the marshland restoration standard. Section 7.3.4, Standard 1 requires major development projects north of 391 Demeter to include tidal marsh restoration.10 A unique characteristic of the wetlands along the RBD shoreline is that even in locations like those of 391 Demeter, tidal marsh vegetation is widely in evidence if varying in density. Commonly associated with the areas of lower density are insufficient flows of tidal waters. Actions to improve those flows may not be perceived as restoration per se, but seem likely to improve the overall health of the marsh.

Recommendation: Revise Standard 1 to include “Marshland restoration or enhancement.”

Chapter 4, Section 4.2 Plan Concept and Figure 4-1 describe areas reserved for open space and marshes as “Restored Wetlands and Open Spaces.” We are very pleased to see restoration emphasized throughout the Plan. Nevertheless, we suggest that these areas instead be referred to as “Protected Wetlands and Open Space” to reflect that the most important action for wetlands is protection.

In addition, please add a Standard in Section 7.3.4 that implements the Community Design narrative calling for 16 acres of restored wetlands and natural open spaces to be “protected and put under long-term management.”11

3. BIOLOGICAL RESOURCES: HABITAT ENHANCEMENT, EXPANSION AND PROTECTION

The Draft Specific Plan Update provides an encouraging and promising vision that describes actions that would increase biodiversity throughout the Plan area. Putting the Urban Forest Master Plan (UFMP) into action along with creating the view corridors and greenway serves wildlife for foraging, nesting, and as navigation pathways for birds, butterflies and a myriad of other species to move through neighborhoods and connect with parks, parklets and open space. It benefits both wildlife and community.

Toward that end, we provide comments meant to help ensure the best outcomes for biodiversity.

The UFMP is an excellent resource for improving the tree landscape, and we look forward to its implementation. However, the absence of a City plan for non-tree species is unfortunate. A combination of trees, understory, meadow, and wetland plants provides habitat services that enhance biodiversity and improve heat and air quality. Native, drought-tolerant, and non-invasive plants are particularly beneficial.

The DSPU discusses non-tree plant selection in Chapters 6, 7, and 8, expressing a preference for native plants but setting no standards (e.g., minimum 50% native) or plant selection list. Without a City list, independent project site lists will vary in native plant ratios.

The UFMP can guide the selection of non-tree plants based on soil, salinity, and groundwater conditions. The San Francisco Estuary Institute (SFEI), primary author of the UFMP, might also provide guidance. For instance, the UFMP notes that Martin Luther King Park requires strategic tree plantings with input from ecological experts due to its location near the Baylands. Similar ecological considerations should apply to all landscaping.

We recommend the DSPU improve its standards and guidance for non-tree plants as suggested above.

- Maintain a treeless waterfront. The entire marsh shoreline of the Plan area, inclusive of tidal marsh habitat under private ownership, is naturally treeless and should stay that way.12 The BCDC band does not apply as nature doesn’t recognize the artificial boundaries of mankind.

Recommendation: Add a wetland-adjacent landscape standard to Section 7.3.3 Urban Forest and Landscaping, requiring that “Wherever there is an adjoining edge of native marsh wetland habitat, (such as along the Bay Trail, the Waterfront Promenade, and along building frontage on the Bay), landscaping must exclude trees and be restricted to upland plants, primarily native and non-invasive, for a setback of at least 100 feet.”

- Reduce predator perches in the built environment. The DSPU recommends limiting locations of the tallest buildings to near the Waterfront. Even with the setbacks and stepbacks proposed, these structures will provide substantial avian perching opportunities that increase predation. Every ledge, balcony, ornamental facade, lighting fixture or rooftop utility structure could be a perch that would potentially endanger marsh wildlife.

Recommendation: We strongly urge that you include a Policy standard requiring all Waterfront property owners to install avian-predator deterrent fixtures on all marsh-facing surfaces.

We are disappointed that the DSPU permits eight-story buildings, especially near the Waterfront, with additional rooftop provisions potentially adding 30 feet in height (see Land Use Chapter comments regarding Section 6.3.1). Wetland habitats thrive under direct light with no shadows from dawn to dusk. Despite setbacks and stepbacks, these buildings will cast long shadows into the wetlands closest to the shore as the sun moves west.

Our concern about shadow effects is heightened by the DSPU’s decision to base stepback and setback measurements on the BCDC band location. The variability of this band reduces the protective effects of setbacks and stepbacks in multiple locations, increasing shadow, light, and noise impacts.

Recommendation: We request increased limitations on tall buildings along the Waterfront, including a combination of reduced height, increased setbacks, and stepbacks measured from the inboard edge of wetlands as delineated in Jurisdictional Determinations.

The DSPU includes strong standards to reduce bird strikes and collision fatalities, but limits their applicability to projects within 1,000 feet of shoreline open space, open water, or wetlands.13 While it is critical to ensure that Bird-Safe Standards are applied near habitat areas, birds will be found outside of these habitat areas, e.g. in every parking lot or neighborhood. The applicability trigger of “any shoreline open space, open water, or wetlands” does not capture the trees, shrubs and other small pockets of nature that will still be used by birds. Birds will frequent the Plan area outside of 1,000-foot zones and can fall victim to unsafe building design in these areas.

Recommendation: We strongly recommend applying the bird safe standards across the entire Plan area to help protect birds from harm while keeping the application of standards consistent.

The DSPU envisions a vibrant waterfront attracting more visitors, picnics, and public events with refreshed landscaping. However, this will result in more trash, balloon decorations, and landscape maintenance, including the use of blowers.

The waterfront is windier than other parts of the Plan area, which poses additional challenges. By implementing these recommendations, the DSPU can better protect the waterfront's unique environment.

- Trash Management: While the DSPU discusses trash management, it overlooks the heightened need for containment on the waterfront. Increased foot and bike traffic, lunch spots, and group gatherings will generate more trash, which can easily escape containment and blow into the marsh and Bay.

Recommendation: The DSPU should set waterfront standards for sufficient, visible trash bins, frequent trash and recyclables collection, and educational signage for visitors.

- Balloons: Wildlife can become entangled in balloon strings or suffer from ingesting balloons, causing severe harm or death. This is a significant issue in all environments, from local parks to oceans.14

Recommendation: The DSPU should prohibit balloons on the waterfront, including terraces and rooftops of buildings, and provide signage in English and Spanish to inform visitors.

- Landscape Blowers: Landscape blowers along the waterfront will annoy shoreline visitors and create dust clouds, spreading dirt, pesticides, herbicides, seeds of invasive plants, and insects into the wetlands and Bay, harming the marsh and wildlife as well as visitors.

- Recommendation: The DSPU should prohibit the use of landscape blowers within 100 feet of the wetland edge.

4. LIGHTING

We were pleased to see several standards included in the DSPU intended to minimize light pollution impacting habitat areas. Revising those standards to address additional known threats and broadening the applicability of those standards would improve the efficacy of the DSPU approach.

Section 6.8.3 Lighting, Standard 2 includes strong standards to minimize ecological impacts on open space. Unfortunately, limiting the applicability of this standard to 100 feet inland of the BCDC band’s edge provides insufficient and ineffective protection for shoreline habitat. Light from tall buildings and streets can travel significant distances, especially on a treeless shore and, as noted in section 1 of this letter, due to the variability of the BCDC band, wetlands in some locations will be closer to new development than others. Importantly, habitat exists in every tree, park, landscaped campus, and residential yard in the Plan area, and residents, too, would benefit from the valuable provisions in Standards 2a, 2b, and 2c.

For instance, Standard 2b requires that "Interior and exterior lighting that is not necessary for safety, building entrances, or circulation shall be automatically shut off from 10 pm to sunrise." Automatic timers are crucial to reduce sky glow that can disorient migrating birds and waste energy, keeping light trespass to a minimum at night.

Additionally, Standard 2c sets a 2,700 Kelvin color temperature for habitat areas, but this requirement should apply everywhere. Lower color temperatures reduce circadian rhythm disruptions for humans and wildlife, as bluer light (around 3,000 Kelvin) is more harmful. Redder lights are better for both habitat and the entire Plan area.

Given that the tallest development would be near the Waterfront, its height and mass would significantly contribute to light glow and trespass.

Recommendation: Apply Standard 2 to the entire Plan area to minimize sky glow, benefiting habitats and residential areas alike.

b. Revise Standard 3 to further reduce light pollution from parking lots

Recommendation: Expand Standard 3, Parking Lighting to require motion sensitive lighting to allow lights to brighten only when a person or a vehicle is perceived as moving. Otherwise maintain light levels very low. Fixed and vehicle headlamp lighting shall be shielded on Bay-facing frontages to protect Bayfront habitat. Lighting shall automatically shut off during daylight hours.

c. Protect wetlands from car headlights

Carefully locate parking and driveways so that headlights of cars heading toward the wetlands do not shine their headlights over the wetlands disturbing nocturnal creatures.

Recommendation: In addition to the DSPU policy prohibiting parking in the 100-foot waterfront setback, parking policy should ensure that driveways and parking lots for buildings are located behind the buildings away from the shore and are not able to cast their headlights onto the wetlands from any position.

5. HAZARDOUS MATERIALS

The DSPU includes goals and policies to protect future residents and workers within the Plan area from hazardous chemicals, whether from existing legacy sources or from future industrial uses. However, the update has not fully addressed the major and possibly cost-prohibitive challenges posed by building in a heavily contaminated area that will be impacted by rising groundwater. The level of concern among some regulators is such that a spokesman for the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency stated that, at the ROMIC site “development is unlikely.”15 Similar concerns exist for other parts of the Plan area. To protect not only users of the new developments but the entire East Palo Alto community and the environment, we recommend the following changes to the DSPU.

Expand Phase II Environmental Site Assessments (ESAs), Vapor Intrusion Assessments, and Health Risk Assessments

Policy LU-5.1 requires a Phase I ESA for any new development or substantial renovation, and a Phase II ESA with soil and groundwater sampling if indicated by the Phase I results. Phase I ESAs are limited to a review of historical land use information and existing chemical analysis data. Figure 3-8 shows that most parcels east of Demeter Street and north of Runnymede would likely require a Phase II ESA based on deed restrictions or known or suspected contamination. The few parcels shown in white likely have no sampling or analysis data available to determine contamination levels. We recommend that all projects east of Demeter Street and north of Runnymede conduct a Phase II ESA.

Policy LU-5.2 requires preparation of a Risk Management Plan (RMP) for all sites with known or potential contamination, including all sites east of Demeter Street/Clarke Ave. The purpose of a RMP is to describe engineering controls to reduce the risk of accidental releases of hazardous materials during construction and site occupancy.16 A RMP is not a substitute for a health risk assessment. As discussed below, a multimedia health risk assessment should be performed at all sites with legacy soil or groundwater contamination.

Policy LU-5.3 requires any project proposing residential, medical, community, civic, or institutional uses to conduct a site assessment or screening for vapor intrusion risk. This list should include commercial uses — there is no risk-based justification for excluding workers at new offices or industrial facilities from this policy. Vapor assessment and mitigation plans should follow the most recent Department of Toxic Substances Control (DTSC)/Water Board guidelines for “future buildings”.17

The DSPU requires assessment of health risks to nearby sensitive receptors for facilities producing potentially hazardous air emissions (Policy LU-4.3), identification of school sites within one quarter mile of those facilities (LU-4.5), and a “targeted health evaluation” for any new developments with sensitive receptors (e.g., housing or schools) within one quarter mile (LU-4.8). These policies fail to protect all the community, as they ignore risks to existing residential areas (other than sensitive populations). They also do not address risks from exposures to nonvolatile contaminants, such as the high levels of arsenic remaining in soil at the former Rhone-Poulenc Superfund site.18

All projects where levels of contaminants in soil, soil vapor, or groundwater exceed screening levels of concern for the proposed land use should conduct a multimedia health risk assessment in accordance with DTSC guidance.19 Risk assessments should consider not only emissions from new facilities but from any project activity producing dust or vapor, including modifications to current site remediation processes, dirt moving, building construction, and post-construction emissions.

East Palo Alto should make available for public comment all draft work plans for project Phase II site assessments, soil vapor assessments, and risk assessments, to provide the community with assurance that the scope will be sufficiently thorough.

A comprehensive groundwater modeling study of the Plan Area is needed to prevent increased human and ecological risk from contaminated groundwater

The DSPU requires individual projects on the shoreline to consider the impact on mobilization of subsurface contaminants of remedial actions (Policy LU-5.1, p. 107) and groundwater rise (p. 305). These policies will be ineffective unless they are part of an area-wide effort to measure water tables and contaminant plumes across the entire Plan Area, not just those on the shoreline. Groundwater does not respect property boundaries. An extraction well on one parcel may result in a change of direction of a plume of contaminated groundwater from another parcel. Construction of underground utilities or structures (e.g. parking garages) will change shallow groundwater flows, potentially moving contamination to areas distant from the project or increasing transport of toxic chemicals to the Bay.

In a recent study, Look Out Below, SPUR evaluated the potential for groundwater rise to mobilize contaminants within the Plan Area, identifying 50 open or closed toxics sites that are vulnerable to sea-level rise.20 Construction of sea walls or levees will not stop groundwater from infiltrating these sites by the end of the century. Pumping groundwater from behind a levee into the Bay could worsen contaminant migration and pull salt water inland, unless a deep barrier is installed along the entire shoreline.

Understanding how toxic contaminants will migrate under these scenarios requires a comprehensive groundwater flow and contaminant transport model. To try to accomplish this on a project-by-project basis is like the proverbial blind man trying to describe an elephant. No single project will have the resources or authority to prepare and maintain such a comprehensive model; it needs to be designed and managed by an organization with that expertise. We recommend the addition of a DSPU policy that the City will identify and pursue sources of funding to support this study. Depending on what the groundwater modeling finds about contaminant flow to the wetlands and Bay, an area-wide ecological risk assessment may be needed as well.

6. ADDITIONAL COMMENTS BY CHAPTER

Chapter 4. Vision and Strategies

The Vision Statement captures many priorities that emerged in public feedback throughout the Specific Plan Update process. However, perhaps due to its heavy focus on the built environment, the Vision neglects to reflect the community’s oft-stated desire to protect East Palo Alto’s treasured wetlands and secure a climate resilient future.

Please add the following underlined words to the end of the Vision Statement to make it more complete.

Chapter 6. Land Use and Development Standards

6.1.2 General Land Use Standards

LU 4.1 through LU 4.8 all caution against introducing potential hazards within 1⁄4 mile (1,300 feet) of sensitive receptors. Though many Life Sciences labs are very like a commercial office, the heart of a Life Sciences building is a laboratory. Therefore, we generally recommend biosafety level labs BSL-1 and BSL-2 labs be a Conditional Use if it is within 1⁄4 mile of residential property, schools, community centers, creeks or the Bayfront in order to address issues of safety as well as noise, deliveries, animal lab facilities, smells from exhausts, lights at night, transport of potentially hazardous agents, and other concerns neighboring communities and mixed use residents may reasonably have.

While BSL-4 high containment labs are not allowed in the DSPU, we also recommend that, for reasons briefly outlined below, BSL-3 labs not be permitted in the DSPU area. BSL-3 “high containment” labs depend on specialized equipment and systems to contain and safely exhaust highly infectious, often lethal agents that are easily transmitted through the air.21 The WO and REC zones are known to be in a high seismic liquefaction zone, with the added structural problem of high ground water causing soil strength problems. In disaster events such as earthquakes, with liquefaction, that cause systems to fail or structures to fail, BSL-3 labs can inadvertently result in potentially deadly consequences for the population. San Carlos and Redwood City (in the Mixed Use downtown area) have banned BSL-3 and BSL-4 labs for public safety.

East Palo Alto’s Safety Element fails to address these new biohazards. San Mateo County Environmental Health staff similarly report that they have no authority or responsibility in biohazard accidents, except for tracking the Coronavirus. The state hazardous materials databases, which emergency responders depend upon, do not have a category for these new biological hazards.

The intent is not to discourage business applicants, but to secure public safety, and to ensure the City and County Emergency Response personnel are aware of and are trained to respond to the presence of approved bio-hazardous materials in buildings in an emergency or disaster situation.

u Make all BSL-1 and BSL-2 Conditional Use in the DSPU, as opposed to Administrative Use permits and ban BSL-3 high containment labs in this very vulnerable area.

6.3.1 Maximum Building Height

The exceptions for rooftop equipment appear to be excessive as height of buildings, including near the bay, has been of major concern to the community. Building heights were reduced in the DSPU in response to these community concerns.

At Waterfront Office (WO) zoning, the 120 foot height limit will be effectively increased to 150 feet if the rooftop equipment is allowed to be 30 feet tall per the rooftop equipment exception (6.3.1 item 4). At Ravenswood Employment Center (REC) zoning, at 60’ allowable height, the resultant effective height would be 90’ tall.

We believe the height increases allowed by this exception could come as a surprise to the community and the City Council who had negotiated a reduction in heights for the Waterfront Office area and in the REC zoning where Biotech labs are now allowed and the only use which would use this exception.

The added height, if allowed along the Bayfront, will also throw additional shadows on the wetlands causing added negative environmental impacts. At a minimum, rooftop equipment screens should be set back from the edge of the roof, if it faces wetlands, so that the setback equals the height of the equipment and screening in order to somewhat reduce the shadowing impact on the wetlands.22

Recommendation: These exemptions to the height limit need to be re-examined in light of community concerns about height limits. Also, screening requirements need to be clarified as to how much of the equipment will be allowed to be screened per DSPU requirements, by equipment codes. Where the building faces wetlands, rooftop equipment enclosures should be set back from the roof edge at least the total height of the enclosure to minimize the shading of wetlands.

University of Texas, Galvaston, biotech lab (BSL-4) rooftop equipment is screened but not fully. The tall exhaust vents for hazardous materials exhausts are exposed, possibly for code reasons.

Albany Medical Center: rooftop equipment with the tall exhaust vents which are not screened. Similar equipment is currently installed on the new San Carlos biotech building on Industrial Road.

6.3.3 Special Height Zones (Stepbacks)

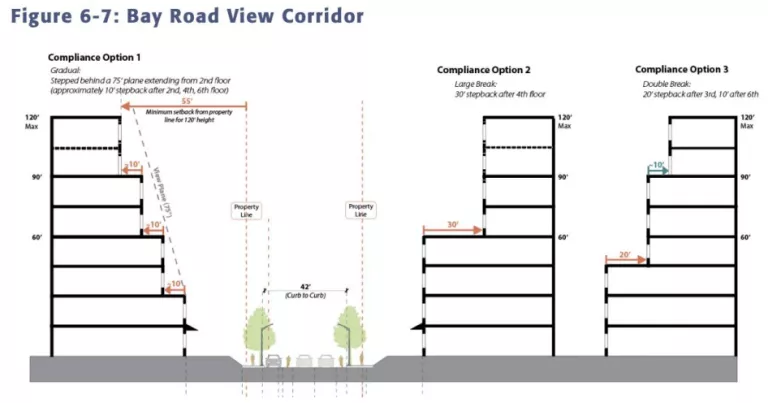

The 2013 RBDSP prioritized preserving view corridors to the Bay, especially along Bay Road, reflecting the community's strong connection to the Bay. This remains a priority today. The DSPU establishes a stepback standard for the Bay Road View Corridor and offers three design options for compliance.

From a pedestrian or driver's viewpoint on Bay Road, the height of the building closest to the street has the most significant impact on the view. This base height should be kept as low as possible. The expansiveness of the view is also defined by the visible sky. We also note that the ground floor of buildings in the Bay Road view corridor will be raised above the street for the DFEs (Minimum Design Flood Elevations per Figure 6.4), making them appear even taller.

The design options are:

- Option 1: 2-story frontage

- Option 2: 4-story frontage

- Option 3: 3-story frontage

We believe that 2- and 3-story frontages would better maintain a connection to the Bay along Bay Road while preserving an open feeling of a big sky. Therefore, we recommend that the scale along the Bay Road view corridor be limited to 2 and 3 stories.

Recommendation: To optimize for an open view to the bayfront, we suggest deleting Option 2.

Figure 6.5 shows Waterfront Transition Zones featuring stepped back building heights. We have noted in previous communications that the Infinity Salvage Yard’s location at the end of Bay Road makes it somewhat anomalous in its relation to the proposed waterfront stepback zones. Note that the outboard edge of waterfront stepbacks follows the shoreline, north of Bay Road, along the Infinity Salvage Yard property’s east edge. Since the DSPU indicates, in Figure 7.1: Parks, Open Space and Trails, that the Infinity Salvage Yard property is intended to be a public park/open space, the stepbacks need to bend and follow the salvage yard’s west edge property line to have their desired effects.

Figure 6.5 - excerpt showing Transition Zones along the Waterfront

This is an important detail if the park becomes a reality. The stepbacks are intended to ensure that buildings fronting the future waterfront public park will have reduced ecological impacts, such as shading of the park, bird collision hazards, and light pollution.

Recommendation: Please revise Figure 6.5 to include the bayfront transition zones to also follow the west edge of the Infinity Salvage Yard at the end of Bay Road, between New Street A and Bay Road.

Chapter 7. Parks and Open Space and Public Facilities

The DSPU is inadequate in terms of requirements for Publicly Accessible Parks and Open Spaces or “PAPOS” (section 7.3, pp 191-193). For example, the DSPU allows residential projects to count courtyard and plaza space as a “publicly accessible park.” Courtyards and plazas in front of residential buildings are typically mere entryways that do not offer either park facilities or green space. These features should only be allowed to count towards the fulfillment of this requirement if they provide demonstrable recreational benefits towards the community, such as usable green space.

In addition, while the DSPU requires a public access easement for PAPOS in non-residential projects, public access easements are not required for residential projects. Easements should be required for all projects within the Plan area, to ensure that PAPOS are not at risk of someday being closed off to the public, converted to a different purpose, or proposed to be used for future development.

Finally, while the DSPU requires that PAPOS in residential projects must be publicly accessible for a minimum of 12 consecutive hours per day, no similar requirement is included in the DSPU for non-residential projects. All projects within the Plan area should be required to make PAPOS available for 12 hours (or from sunrise to sunset, as is typical for public parks) in order to count towards fulfillment of this requirement.

“A key component of the Plan is a laying the framework for a contiguous public waterfront amenity space integrated with a future flood control improvement. This space would contain active and passive open spaces, and be designed to maximize community gathering and recreation, while supporting FEMA-accredited flood control infrastructures.”23

Outdoor recreation access is critical for local communities' health and economic benefits. However, the waterfront borders a wildlife habitat, and various recreational activities can impact this habitat. Research shows that even quiet, non-consumptive activities like hiking and wildlife viewing can negatively affect wildlife behavior, habitat use, reproduction, and survival.

To balance public access and species conservation goals, we recommend using the precautionary principle, considering physical separation of uses, and directing the most impactful activities away from sensitive areas. Active recreation areas, such as sports courts, picnic areas, and amphitheaters, should be located far from the shoreline. Passive recreation areas, like the Bay Trail and quiet zones, should be prioritized near the trail. Additionally, pets should be leashed at all times to protect habitat areas.

Recommendation: Add the underlined clause to Standard 1, Maximum Public Access: "All projects along the waterfront shall increase public access to the Bay to the 'maximum extent feasible' in accordance with the policies for Public Access to the Bay, while respecting and protecting habitat and keeping active areas furthest from habitat areas."

Chapter 8. Mobility and Streetscape

8.3 Multimodal Networks

The DSPU’s Parks and Open Space Policy POS-1.2 calls for establishment of “a robust non-vehicular network of publicly accessible greenways, paseos, multi use trails, and linear parks that promote safe pedestrian and bicycle use throughout the Plan Area.” This has implications for 8.3.1 Pedestrian Network, 8.3.2 Traffic Calming, and 8.3.3 Bicycle Network.

Creating a Slow Safe Green Network24

During COVID, many cities around the Bay Area and the world developed slow, safe street networks for bicycles and pedestrians. These changes, often made permanent, shifted cities from automobile dominance to healthier, more enjoyable lifestyles.

The DSPU plan to add new streets and create walkable blocks can evolve into a comprehensive slow, safe, green network. This network would prioritize pedestrians, bicycles, and micro-mobility with a speed limit of 15 mph for all traffic. Features would include shade-providing trees, wide or undefined sidewalks, green stormwater drainage, native plants, and active frontages with outdoor seating.

Figures 8-2 and 8-3 show the potential for combining pedestrian and bicycle networks into a single “Slow, Safe, Green Network” with safe crossings at trafficked streets. Additionally, East Palo Alto’s Urban Forest Master Plan aims to “Become a Tree City USA,” providing a lush canopy for pedestrians and bicyclists.

Recommendation: Combine the pedestrian and bicycle networks in the Parks, Open Space, and Trails Concept (Figure 7-1) into a single "Slow, Safe, Green Network" in the SPU area. Additionally, please consider including the following policy within Goal MOB-1 Enhance pedestrian and bicycle circulation throughout the Plan Area.

Micromobility has grown considerably in popularity and provides mobility at about the same speed as bicycles. Micromobility includes bikes, e-bikes, e- scooters, skateboards, e- skateboards, kick scooters, onewheel, in line and roller skates, segways, unicycles, tricycles, handcycles, mobility scooter, quadracycles, and electric and manual wheelchairs.

Recommendation: Integrate micromobility into the bicycle network and revise the title and description of the Bicycle Network in Section 8.3.3 to reflect the addition.

Chapter 9. Utilities

Stormwater and a Runnymede Pump Station

In Section 9.5, Stormwater System Improvements, the DSPU discusses the City’s plans for future conditions due to climate change. These plans include the possibility of adding a pump station to the Runnymede Storm Drain System. In discussion above about the Don Edwards National Wildlife Refuge, we mentioned that the City needs to work closely with the Refuge as a partner if a pump station is to be built. The existing stormwater outfall flows directly onto Refuge marshland that hosts the federally endangered Ridgeway rail. We are concerned that if this outfall location is used, the force of pumped stormwater is likely to dramatically increase stormwater impact on the marsh, perhaps excavating some portion of this healthy, established tidal marsh, which is a potential that must be avoided.

Recommendation: Please include a requirement to contact the Refuge early in pump station planning in both the DSPU and any other relevant City planning documents.

In Summary, we hope that these comments on the Specific Plan Update are useful, and we are available to discuss them with you and the project team. We look forward to continuing to be involved in this visionary plan for East Palo Alto as it moves forward.

Respectfully submitted,

Jennifer Chang Hetterly

Bay Alive Campaign Coordinator

Sierra Club Loma Prieta Chapter

Eileen McLaughlin

Board Member

Citizens Committee to Complete the Refuge

Alice Kaufman

Policy and Advocacy Director

Green Foothills

Chris MacIntosh

Conservation Committee, Chair

Sequoia Audubon Society

1 Jurisdictional Determination (JD) is a two step process. First a Jurisdictional Delineation is performed to identify and delineate areas within a site that qualify as Waters of the United States (WOTUS). Then a Jurisdictional Determination can be made for lands so delineated as to whether those waters will be regulated under Section 404 of the Clean Water Act and subject to a permit. Reference: https://www.epa.gov/cwa-404/how-wetlands-are-defined-and-identified-under-cwa-section-404

2 Cooperative Licensing Agreement discussed with Troy Reinhalter, Raimi Associates July 17, 2024 and sent to him by email the same day.

3 Don Edwards San Francisco Bay National Wildlife Refuge Comprehensive Conservation Plan 2012: https://ecos.fws.gov/ServCat/Reference/Profile/43999

4 Refuge Contact: Ann Spainhower, Manager, Don Edwards San Francisco Bay National Wildlife Refuge; ann_spainhower@fws.gov, 510-792-0222.

5 Ann Spainhower, Manager, Don Edwards SF Bay NWR; ann_spainhower@fws.gov, 510-792-0222

6 Preliminary Application-Project Description and Site Plans July 2020, Emerson Collective; https://www.cityofepa.org/sites/default/files/fileattachments/planning/project/16491/200731_epa_waterfront_pre-application_reduced.pdf

7 The Landing Architectural Material-Part 1 2021, Harvest Properties; https://www.cityofepa.org/sites/default/files/fileattachments/planning/project/15121/the_landing_architectural_material_-_part_1.pdf

8 “Permitted Bay Fill. Minimal fill may be permitted if the fill is ‘necessary and is the minimum absolutely required to develop the project’ in accordance with BCDC requirements.” DSPU Section 7.3.2, Standard 12, p. 197

9 “Bay Fill. Based on scientific ecological analysis, project need, and consultation with the relevant federal and state resource agencies, fill may be authorized for habitat enhancement, restoration, or sea level rise adaptation of habitat.” DSPU Section 7.3.4, Guideline 6, p. 203

10 “Marshland restoration. Major development projects north of 391 Demeter shall include restoration of significant areas of tidal marsh along the perimeter of the Bay.” DSPU Section 7.3.4, Standard 1, p. 202

11 DSPU Section 4.4.2 Community Design, p. 80

12 East Palo Alto’s Urban Forest Master Plan (UFMP) speaks to the topic of trees and tidal marsh habitat: “While tree planting throughout the city can help create wildlife corridors and provide resources to animals, it should be avoided in and directly adjacent to tidal marsh areas along the Bay. These special and unique habitats support endangered species like the salt marsh harvest mouse, and offer an opportunity to experience a remaining patch of the historical ecosystem. Tidal marsh does not naturally include trees so tree planting is not recommended in these areas. The addition of trees could even have detrimental effects in the tidal marsh, as it could allow raptors new places to perch and catch the endangered salt marsh harvest mouse and other wildlife.” UFMP Appendix IV, p. 6.

13 DSPU Section 6.8.4, Bird Safe Standards, Standard 1: Applicability, p. 171

14 US Fish & Wildlife Service, Balloons and Wildlife: Please don’t release your balloons: https://www.fws.gov/story/2015-08/balloons-and-wildlife-please-dont-release-your-balloons

15 Steve Armann, Manager, Corrective Action Office, EPA Region 9, January 24, 2024; Presentation: Former Romic Bay Road Holdings for Youth United for Community Action (YUCA).

16 https://dtsc.ca.gov/california-accidental-release-prevention-program-calarp-fact-sheet/

17 Supplemental Guidance: Screening and Evaluating Vapor Intrusion. FINAL DRAFT. California Department of Toxic Substances Control. California State Water Resources Control Board. February 2023.

18 Covenant of Deed Restriction, Rhone-Poulenc, Inc. 1990 Bay Road, May 13, 1994.

19 https://dtsc.ca.gov/human-health-risk-hero/

20 Look Out Below. SPUR Case Study. May 2024. https://www.spur.org/publications/spur-report/2024-06-12/look-out-below

21 American Laboratory: Exhaust discharges from BSL laboratories may be highly toxic (or noxious) or both. Their danger to people covers a broad spectrum, which may be mildly annoying to seriously unhealthy. Also, government agencies are continually setting more stringent standards, with allowable exposure limits dropping lower and lower. Obviously there is no room for tolerance with regard to possible contamination from some agents that are exhausted at BSL Level 3 and 4 facilities. In many cases, even if the fumes are not toxic, public tolerance for odiferous discharges has decreased sharply in recent years.

22 American Laboratory: These shortcomings can be added to a relatively new concern in many locations, that is, the sight of tall exhaust stacks on a building’s roof, which usually imparts negative connotations in a community—in other words, another neighborhood polluter. A Case Study in Evaluating Biofacility Exhaust Systems,.... Community ordinances often restrict total building height or the height of various appurtenances and accessories above rooflines. In addition, tall exhaust stacks can impart negative connotations in a community....

23 DSPU Section 7.3.2 Waterfront Parks, Open Space, and Levee, p. 195.

24 Guideline for Master Planning a Sustainable Green Street Network. How to move from Vision to Practice, Sustainable Land Use Committee, Sierra Club Loma Prieta.