by Alanna McKee

If you live in a town that didn’t ask people to conserve water this last summer and fall (and if you didn’t look at the streams and rivers around you), you might not have noticed it, but most of New England was drying up. By early October, 90% of Massachusetts was in a drought, with more than 1/3rd of the state experiencing extreme drought – or a ‛D3’ designation.

The middle of October was the peak of the drought for Massachusetts.

According to the University of Nebraska’s National Drought Mitigation Center, which monitors drought levels and drought-related incidents throughout the country, extreme drought in Massachusetts typically causes a wide array of problems, including major crop losses, increased wildlife diseases, and dead aquatic life.

Seeing so much red on a map is alarming, but what did those red and red-toned patches actually mean in the real world this year? Here are just a few of the effects we saw: Massachusetts had more than 1,000 wildfires (four times more than the year before), cranberry bogs dried up, wells went dry in New Hampshire, many of Massachusetts’s rivers stopped flowing, and fish died as their homes dried up.

All of New England suffered with drought this year, and, at the time of this writing, 99% of New Hampshire and all of Rhode Island are still having one.

For more information on the drought’s damage – both environmental and human – take a look at MassLive’s three-part series of articles on the topic.

The national news gives us images of droughts out West, where there’s so little water that everyone experiences it first hand; everyone is asked to cut back on their toilet flushes and everyone feels the pain in their wallet if they overdraw from the tap. (My husband and I have friends in California who, moving into a new house, thought to perk up their new yard by watering the lawn a little bit, only to get a $2000+ water bill the next month.) And the wildfires in the West have, of course, been terrifying in their destructive power.

Our less-visible New England droughts may seem quaint by comparison, but that doesn’t mean they’re not destructive. Take Massachusetts as an example. In a state that usually receives a lot of precipitation (our annual average puts us in the top quarter of U.S. states), our animals and plants are adapted to live in environments that contain steady inputs of water – so, when adequate amounts of water aren’t consistently available throughout the warm months, the natural world suffers, and often dies.

A key thing to understand is that New England’s typically steady water supply comes from three different sources – rainfall, snowmelt, and groundwater. And, while individuals can’t immediately affect the way rain falls or snow melts (that’s the long-term work of fighting climate change), we can increase the amount of groundwater available – and that’s where we need to take action right now.

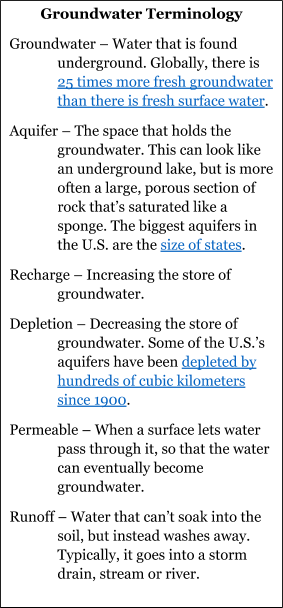

Groundwater accumulates in spaces called aquifers (think of them as nature’s underground storage tanks). When things are working optimally, groundwater’s always there, providing drinking water in our wells, bubbling up in springs to spill out as streams, and keeping wetlands wet. But when an aquifer gets overdrawn (by us pumping too much out of our wells), there isn’t enough groundwater to sustain things when the rain stops. That’s what happened to us last summer and fall. Tellingly, the Plymouth-Cape Cod area, which gets most of its water supply from groundwater, was one of the hardest-hit places during our recent drought. Going forward, as climate change shifts rain patterns towards more extreme flood-drought cycles, we will have to rely on groundwater more and more because we will have more periods without rain.

Groundwater accumulates in spaces called aquifers (think of them as nature’s underground storage tanks). When things are working optimally, groundwater’s always there, providing drinking water in our wells, bubbling up in springs to spill out as streams, and keeping wetlands wet. But when an aquifer gets overdrawn (by us pumping too much out of our wells), there isn’t enough groundwater to sustain things when the rain stops. That’s what happened to us last summer and fall. Tellingly, the Plymouth-Cape Cod area, which gets most of its water supply from groundwater, was one of the hardest-hit places during our recent drought. Going forward, as climate change shifts rain patterns towards more extreme flood-drought cycles, we will have to rely on groundwater more and more because we will have more periods without rain.

So, we need to have more groundwater in our aquifers (akin to having a fuller storage tank).

How do we do that?

We’ve got two tools at our disposal: decreasing water consumption (so that the tank doesn’t go down as much), and increasing groundwater recharge (putting more water back in the tank).

TOOL #1. Here are some specific things we can do to decrease water consumption.

Conserve, conserve, conserve. Beyond the usual measures, like fixing leaks and turning off the tap while you’re brushing your teeth, please consider the following……

Collect rainwater. The easiest way to do this is by installing rain barrels next to your downspouts. Check out this rainwater collection calculator that’ll show you the astonishing amount of water you can collect.

Mass.gov provides a resource that can help you find, install and use rain barrels, al0ng with information and links to other water conservation tools like dual-flush toilets, low-flush toilets, and low-flow showerheads. I would add to the advice on that site, that you can usually find used rain barrels on Craigslist. Also, when installing a rain barrel, it’s better to use a diverter to direct downspout flow over to the barrel, rather than chopping off the bottom of your downspout and sticking the barrel directly underneath. (In the picture of my rain barrel, above, the downspout’s on the far left edge of the image. My diverter is already plugged up for the winter, and the rain barrel is empty and sealed up on top. That way, expanding ice won’t burst it from the inside.)

Ask your state senator and representative to support two important bills, which will facilitate state-wide conservation during droughts. Since water is a shared resource (even if you have a private well, you and your neighbor pull from the same aquifer), it’s necessary to have a coordinated, state-wide effort to reduce water use during drought times. Such an effort can help to maintain our common water supply.

In 2019 Massachusetts made strides towards effectively addressing drought with the Drought Management Plan. Now there are two bills in the state legislature’s pipeline that add necessary improvements, including giving the Secretary of Energy and Environmental Affairs the authority to order water conservation measures in drought-stricken areas. These bills – S.535 and H.762 – are endorsed by the Massachusetts Rivers Alliance, an umbrella organization made up of 70+ water-concerned organizations (including the Massachusetts Sierra Club).

Please take a few minutes to find your senator and representative, and let them know that you’d like them to support S.535 and H.762.

TOOL #2. Here are some specific things we can do to increase groundwater recharge.

Rain Barrels – In another plug for rainwater collection, it’s important to emphasize that this practice not only conserves water, it also helps increase groundwater.

That’s because, when you collect rain during a storm (especially when it’s moving fast, pouring off of your roof) you’re capturing water that would most likely otherwise turn into runoff. And later, when you water your garden with it, you’re releasing that water slowly, at a time when the ground is no longer so saturated, thereby increasing the likelihood that those specific gallons of water will seep into the ground, starting their journey down to the aquifer below where they will become groundwater.

Rain Garden – If your yard has a spot that gets soggy when it rains, consider yourself lucky! You can plant a rain garden that will collect that accumulating water and encourage it to percolate down into the soil. Take a look at the GreenScapes website to get more information and instructions. Photo: Rain garden. Source: Wikimedia. By James Steakley.

Aerate your lawn

Aerating your lawn means using a machine to physically poke lots of holes in it. Because this increases water’s ability to penetrate down to the grasses’ roots, it also reduces runoff (which is always a win for water quality, because it reduces the amounts of pesticides, road pollution and animal waste that end up in our water supplies). You can rent a lawn aerator from Home Depot.

Use permeable pavers instead of asphalt or concrete

Standard asphalt and concrete are essentially impermeable. When you’re hardscaping your yard, there are lots of ways to keep things semi-permeable, like laying pavers with spaces between them. The larger the ratio of space-to-paver is, the better.

Asphalt driveways are especially bad runoff makers. Instead of using asphalt for your driveway, consider laying something like Turfstone, which is a diamond-patterned grid made of concrete, and has a ratio of almost equal parts concrete and space. You can let grass grow in the spaces, or fill them with gravel or sand.

There are so many things we can do to improve our water supply. We’re ending a very bad dry season, but let’s learn from what happened these past months, and be a more resilient place going forward – a place with animals, plants, and humans that can survive the coming year, and the year after that, and the year after that….

Now is the time to act.