Earth’s Global Annual Temperature Breaches 1.5°C for the First Time

2023 was the hottest year on record, and scientists agree the warming trend will continue without the rapid phase-out of fossil fuels

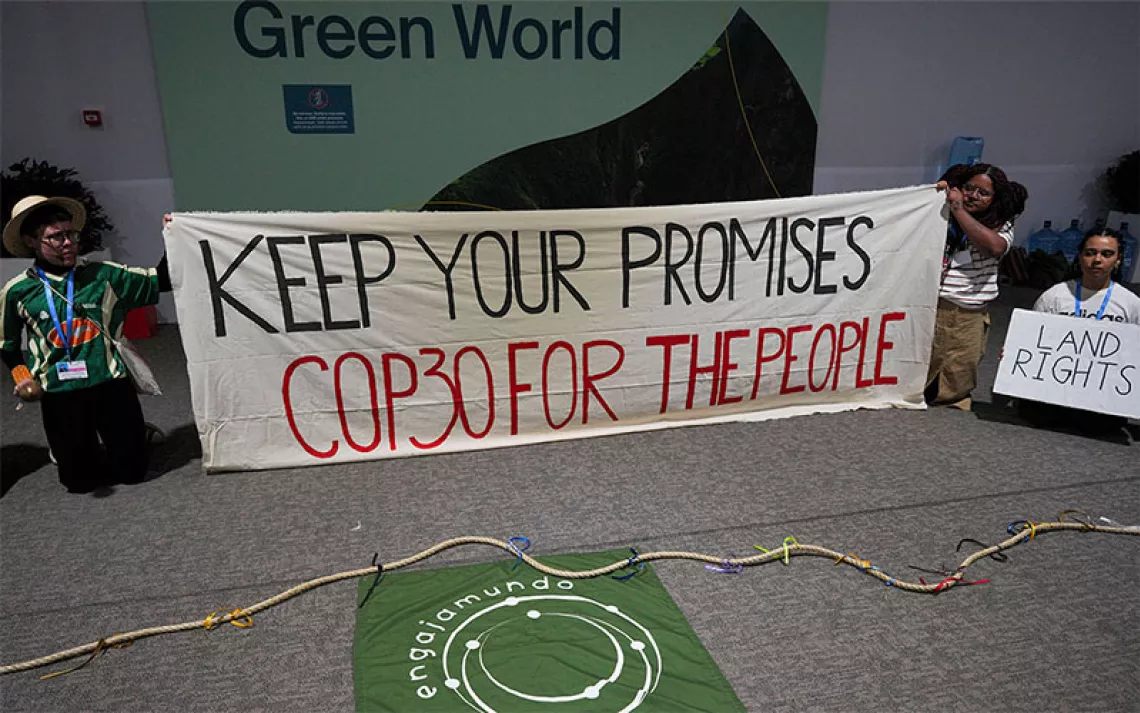

Photo by Press Association via AP Images

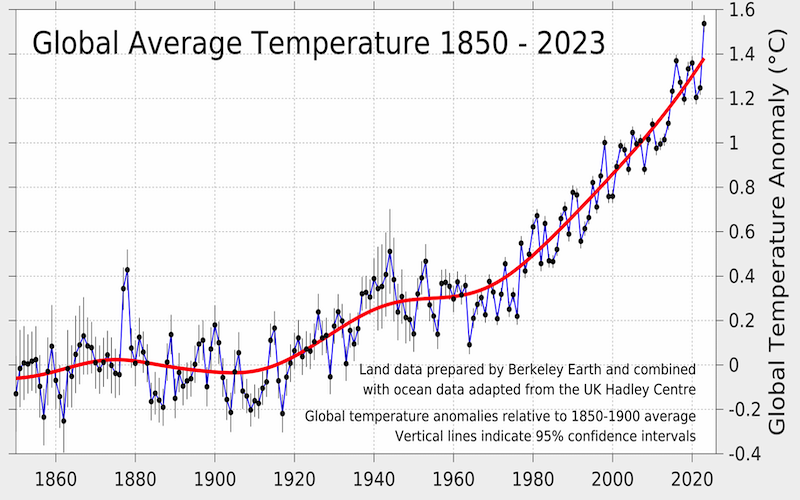

A leading independent climate-reporting institution, Berkeley Earth, has found that the planet’s global annual temperature breached 1.5°C, or 2.7°F, above preindustrial levels for the first time.

Scientists have long warned that the grim milestone was coming. For decades, research has clearly established that the emission of greenhouse gases, such as carbon dioxide (CO2) and methane (CH4), were warming the planet—mainly due to human use of fossil fuels like coal, oil, and gas for energy. Since the Paris Agreement was ratified in 2016, the world’s biggest emitters of those gases agreed that they must hold average global temperature “well below 2°C,” or 3.6°F, and committed to 1.5°C as a threshold. Since then, the use of coal, gas, and oil for energy has continued unabated; global carbon dioxide emissions from burning those fossil fuels reached record highs last year; and temperature records were broken around the world.

Scientists agree that what comes next depends entirely on whether the world’s biggest industrial societies transition off fossil fuels to renewable sources of energy before it’s too late.

According to Berkeley Earth, the average global temperature for 2023 was 1.54°C higher than the average for the preindustrial period of 1850–1900. Berkeley Earth also confirmed what the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA), NASA, and the leading European climate-reporting agency Copernicus reported this month: 2023 was the hottest year ever recorded. Copernicus found that the annual average temperature for 2023 was 1.48°C above preindustrial levels, adding that by February of this year, it would likely show a 12-month average above 1.5°C. NASA and NOAA found that 2023 was 1.18°C above the average. In the United States, it was the fifth hottest year since 1850.

That rate of warming has squarely tracked with the rise in carbon dioxide emissions from human activity. In 1850, there was approximately 285 parts per million (ppm) of CO2 in the atmosphere. Today, there is approximately 420ppm—a near doubling. The scale, rate, and speed of that rise of planet-warming gases in such a short period of time is unprecedented in the geological record, amounting to a massive geophysical experiment. Ecosystems and the living species that depend on them were not designed to adapt to such a rapid change in their environments.

At a joint NOAA-NASA press conference, Sarah Kapnick, NOAA’s chief scientist, said, “The findings are astounding.”

A hotter planet means more extreme climate conditions that impact every level of society, and those conditions were felt around the world last year. At least 2.3 billion people—roughly 29 percent of Earth’s population—experienced warmer-than-usual temperatures in 2023. New national records for annual temperatures were set in 77 countries. Record low Antarctic sea ice was observed during the winter. According to a recent United Nations report, nearly a quarter of humanity—1.84 billion people—lived in drought conditions in 2022 and 2023. In the United States, according to NOAA, there were a total of 28 weather- and climate-related disasters in 2023—a record number—that cost US taxpayers $1 billion or more, totaling $92.9 billion. Since 1980, there have been a total of 376 such disasters, costing US taxpayers $2.6 trillion. In Canada, 45 million acres across the country burned after it saw record-breaking temperatures in 2023, releasing 1.7 billion tons of CO2 into the atmosphere. In South America, a scorching heat wave baked Brazil and surrounding countries between July and August.

At the beginning of 2023, researchers published estimates for how hot it would likely get by the end of the year based on the latest data. Their estimates were way off. NOAA, for example, offered just a 7 percent chance that 2023 would be the hottest year on record.

“It was much warmer than any of us thought was plausible,” Zeke Hausfather, climate scientist and energy systems analyst at Berkeley Earth, told Sierra.

A modest La Niña event kicked off the year with a cooling trend, but then El Niño took hold—a cyclical warming pattern that occurs roughly every three to five years. The natural warming variability that this pattern produces contributed to the long-term warming trends from human activity. Also, a 2022 volcanic eruption in Tonga emitted a large amount of water vapor into the atmosphere, which has a planet-warming effect; an uptick in the 11-year solar cycle likely contributed a degree of warming; and the phase-out of sulfur aerosols from marine fuels and at coal-fired power plants also likely played a role. The phase-out of those aerosols helps clean up air pollution, but that air pollution also has the effect of reflecting sunlight back into the atmosphere, so less air pollution can inadvertently expose the planet to more heat from global warming.

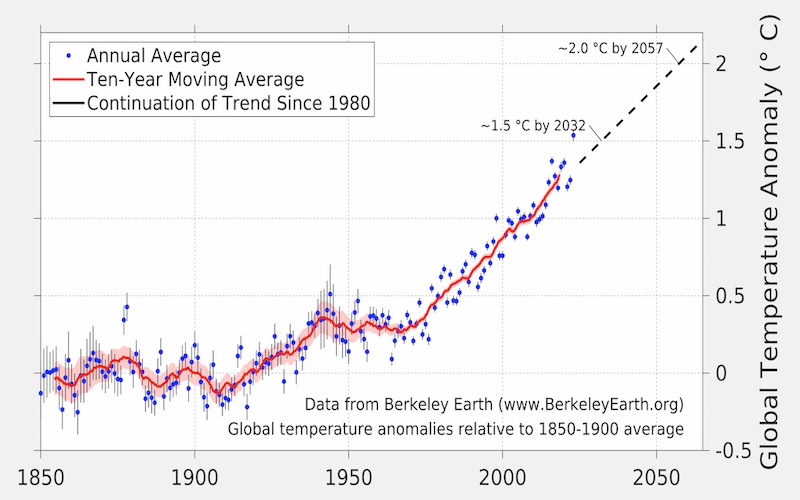

El Niño is expected to peak next month and start to decline. Even so, scientists expect 2024 to potentially be as hot if not hotter than 2023. According to Berkeley Earth, if the warming trend from the last 40 years continues, the planet will reach a long-term average temperature increase of 1.5°C above preindustrial levels by 2032 and 2°C by 2057.

Government agencies and climate modelers tend to offer different assessments of Earth’s average global temperature due to the varying methodologies they use to assess the data. There are two types of temperature records: observational and reanalysis. Berkeley Earth, for example, exclusively uses observational data gathered from approximately 40,000 weather stations around the world, weather balloons, sensors on ships, and 3,000 automated buoys that float on the ocean. That land and ocean temperature data is averaged for a particular month and can be tracked back as far as 1850. Reanalysis, which Copernicus and the Japanese Meteorological Agency use, produces a more limited data set: It relies on current global weather data, which researchers then run back in time to produce global temperature models going back to approximately 1950.

Crossing that 1.5°C threshold for a single year does not make for a long-term average—researchers like to see at least five years of data to determine a trend. But it is a sobering reality check for policymakers. Scientists expect that once that threshold is crossed for a single year, the chances of it becoming a long-term average are much greater. Two years of global annual temperature exceeding 1.5°C would suggest that the chances of keeping warming below that threshold are increasingly out of reach.

“It’s crystal clear that the long-term warming the world is experiencing today is entirely due to human activity,” Hausfather told Sierra. “If we just look at natural factors like changing solar output or volcanoes, the world would actually be slightly cooling over the last 30 years. We as an industrial society collectively decide how warm the world is going to get by our future emissions. We need to rapidly transition off fossil fuels toward clean energy and reduce emissions as quickly as possible.”

Hausfather also said that it is likely already too late to limit warming to 1.5°C.

“The global economy can’t turn on a dime. We’ve waited too long, and the global carbon budget is vanishingly small,” he said. “If we don’t do anything in the next decade, we’ll be having the same conversation about 2°C that we’re having about 1.5°C. Now is the time to act.”

The Magazine of The Sierra Club

The Magazine of The Sierra Club