Loopholes and Fractures Make for Un-United Nations as COP29 Ends

Fossil-friendly language permeates draft texts and tensions between developed and developing nations remain

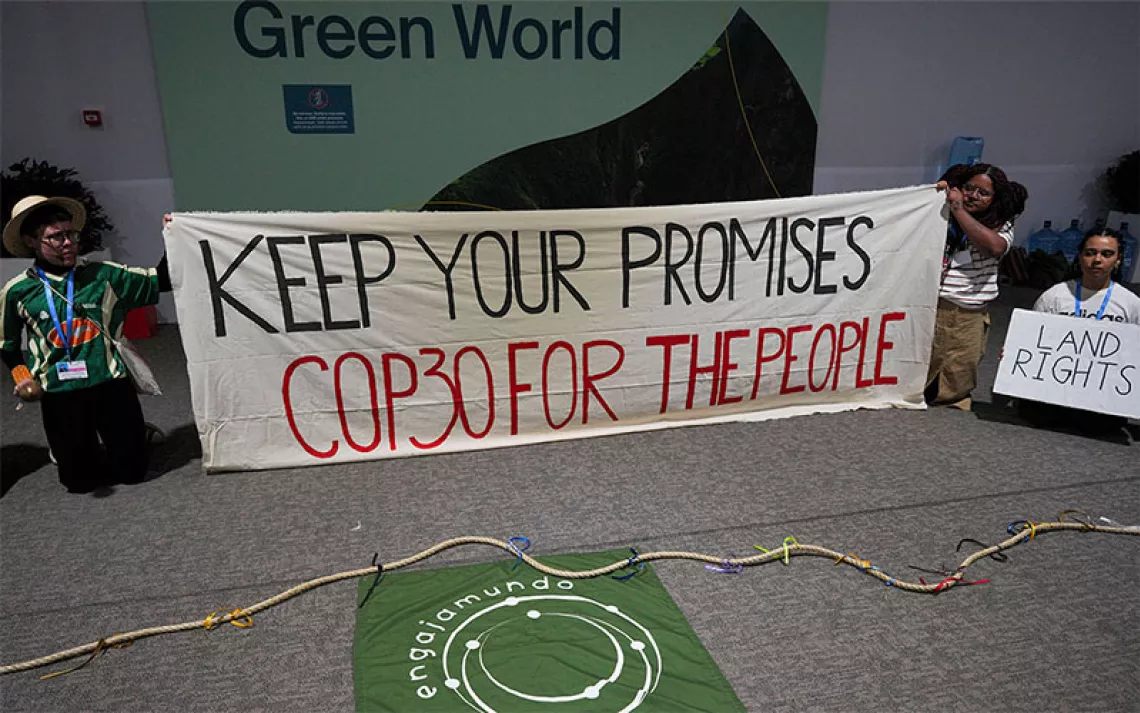

Conversations with negotiators from developing countries in the hallways revealed frustration over the lack of prioritization by developed nations on adaptation.| Photo by Nour Ghantous

The last time a UN Climate Change Conference took place in Eastern Europe was in 2018, when around 22,000 delegates gathered in Katowice, Poland—a fitting, if ironic, choice given the city’s deep roots in coal mining. Back then, the world was grappling with sweeping California wildfires, Donald Trump’s presidency, and the challenge of creating transparency and accountability mechanisms to hold countries to their climate promises.

Fast-forward six years and we’re wrapping up yet another such conference (known as the Convening of the Parties, or COP) in yet another coal-reliant city—Baku, Azerbaijan. The smog is thick, but the air of déjà vu is even thicker. California still burns, Sudan and Spain remain submerged under historic flooding, Trump is poised to return to office, and negotiators are still grappling not only with holding nations to their pledges but also with agreeing on the parameters of those pledges in the first place.

COP29 officially ends today, but nations are not expected to vote on an agreement until Saturday. The current draft text released today falls far short, offering less than a quarter of the financing needed from wealthy nations—many of which are the largest emitters in the world—to help poorer countries adapt to climate disasters and transition to green economies. The drafted shortfall in funding is also not entirely grant-based but includes loans. This agreement risks causing debt crises and undermining economic stability with disproportionate impact to the most vulnerable nations, jeopardizing the world’s ability to stay beneath the 1.5°C target for average global temperature increase, and eroding trust in global climate finance.

A “Finance” COP only by name

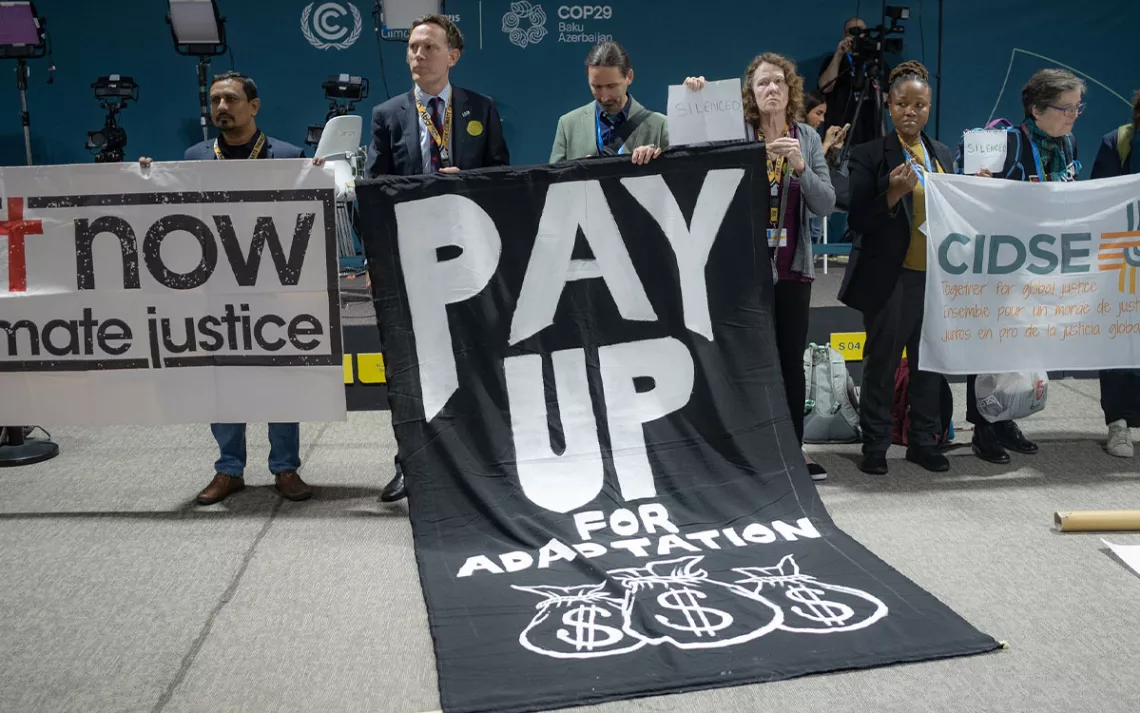

At COP29, the NCQG, or “new collective quantified goal,” has taken center stage, aiming to secure annual funding commitments from developed nations to funnel toward supporting developing countries in transitioning to green economies and building resilience against the surmounting impacts of climate change. While the overarching message from delegates remains clear—climate mitigation and adaptation must be financed—the negotiating table, the nucleus of COP discussions, is fractured, particularly between developed and developing nations.

The divisions are rooted in a history of unmet promises. In 2009, wealthy nations pledged to deliver $100 billion annually in climate finance to developing countries by 2020. However, according to the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development, this target was only achieved in 2022—two years too late.

Now, the world faces the urgent need to meet the 2015 Paris Agreement’s target of limiting the global average temperature increase to 1.5°C above pre-industrial levels. Developing nations experiencing surmounting climate disasters, as well as scientists and activists, have amplified the call for deeper financial commitments. Yet the conference deadline has arrived, and a canyon remains between the demands of developing nations, who need trillions in grants, and the developed nations, who are reluctant to commit beyond billions.

Sign up to receive Sierra News & Views

Get articles like this one sent directly to your inbox weekly.

With this action you affirm you want to receive Sierra Club communications and may vote on policy designated by the Sierra Club Board.

The tension was palpable during a press conference on Wednesday when Agence France-Presse asked Uganda’s UN representative, Adonia Ayebare, and Bolivia’s representative, Diego Pacheco, about the prospect of a $200 billion climate finance target. Their joint response—“Is it a joke?”—underscored the frustration of nations whose very survival depends on these funds.

The draft NCQG text itself highlights the enormity of the challenge, noting that developing countries need nearly $7 trillion by 2030 to transition to greener economies, which includes $387 billion annually for adaptation efforts that would build resilient communities to brace for climate disaster.

Contradictorily, the latest draft includes an offering of $250 billion annually, less than a quarter of what is required, and ignores poor countries’ calls for exclusively grant-sourced funding, citing instead a “combination” of sources, including loans, which fuels the threat of steeping them further into debt.

Minor revisions are expected on Saturday before nations take a vote on adopting the text. As the negotiations enter their final hours, key fault lines remain unresolved: the so-called quantum (the total amount of funding), the contributor base (who should pay), and the sources of finance. These sticking points will determine whether the NCQG becomes a symbol of progress or another missed opportunity in the battle against climate change

What about fossil fuels?

Though the cessation of new oil and gas and a transition to clean energy is a non-negotiable for limiting global average warming to 1.5°C, it was not up for discussion this year. At COP28 in the United Arab Emirates, countries debated an agenda to phase out fossil fuels and landed on an agreement to “phase away” from them instead. Small Island States criticized the final text for allowing a “litany of loopholes” that enable the production and consumption of coal, oil, and gas to continue.

This latest text of the NCQG goal marks a stark departure from the draft text released earlier, which, while it did not exclude fossil fuel finance altogether, at least acknowledged the need to address financial flows related to fossil fuels. As it stands today, the door is very much open to fossil-fueled finance.

“Finance that prolongs the fossil fuel industry could be dishonestly counted towards pretend climate finance. That's not good,” warned Andreas Sieber of 350.org at a press huddle at the conference on Thursday.

Fears about fossil fuel propagation gripped experts and activists on November 11, the first day of the conference, as the gavel brought down Article 6.4—an agreement to establish a UN-centralized body to regulate the voluntary carbon market.

“Buying carbon offsets is simply not climate finance. If you are buying carbon offsets to avoid domestic mitigation, you are not providing climate finance. This is a very worrying idea. It makes no sense.”

Unlike government-regulated carbon trading systems, the voluntary carbon market allows companies and organizations to buy and sell carbon credits on their own terms to offset their emissions, often as part of corporate sustainability efforts. The contentious speed of the agreement bypassed further negotiations that could have tackled critical loose ends, such as dealing with projects where carbon savings might be reversed.

“The speedy decision was problematic because it not only left numerous issues unresolved but it also set an alarming precedent that undermines the consultative decision-making process,” Carbon Market Watch’s Khaled Diab told Sierra.

Isa Mulder, a policy expert at Carbon Market Watch, stressed the importance of clear boundaries moving forward. “It is essential to ensure a strict firewall between the new climate finance package, Article 6, and the voluntary carbon market,” she said in a written statement at the end of the first week of COP29.

Yet the NCQG text’s wording qualifies carbon markets as a potential contributor to the global finance goal—a prospect that has raised alarm among experts.

“Buying carbon offsets is simply not climate finance,” said Sieber. “If you are buying carbon offsets to avoid domestic mitigation, you are not providing climate finance. This is a very worrying idea.”

Along with the Article 6.4 agreement, the NCQG could allow companies to claim climate finance for buying carbon credits from projects that capture carbon dioxide and use it to extract more oil—a process called enhanced oil recovery.

“It doesn’t make any sense,” added Sieber.

These unresolved tensions over fossil fuel finance and carbon markets could make or break the credibility of the new climate finance goal.

What does the US think about this?

Throughout COP29, the United States’ presence felt notably detached compared with many smaller nations that showcased their climate action efforts through large, vibrant pavilions. While countries with substantially lower emissions used the conference to highlight their decarbonization and adaptation initiatives, the American presence was in the form of a modest “US Center,” a pavilion that drew little attention. President Biden’s absence further underscored this lackluster engagement, particularly in negotiations.

The US delegation itself was strikingly small, dwindling from 770 last year to 405 registered party members this year—less than half the size of China’s or Russia’s delegation and far below Indonesia’s 810 and Nigeria’s 634. This perceived indifference was magnified by the looming Trump administration’s push to expand the fossil fuel industry and dismantle the Inflation Reduction Act—a law that promotes domestic clean energy, among other things—undermining the country’s credibility on climate leadership.

While the US has used its messaging outside the negotiation rooms to signal a commitment to climate action, its position at the table tells a different story.

The US supports providing climate finance, but only from a baseline of $100 billion—less than a third of what developing countries need annually for adaptation alone. It has also pushed to expand the contributor base beyond developed nations, a move critics argue shifts responsibility away from the largest historical emitters. Notably, the US contributes an estimated 13.51 percent of global emissions.

Asked what the United States’ flexibility and involvement has been like during these final negotiations, director of International Climate Politics Hub Cat Abreu told Sierra that the greatest flexibility the US is offering is its ongoing silence.

A senior US official released the following statement in response to the latest draft agreement: "It has been a significant lift over the past decade to meet the prior, smaller goal. $250 billion will require even more ambition and extraordinary reach. This goal will need to be supported by ambitious bilateral action, MDB contributions, and efforts to better mobilize private finance, among other critical factors."

On the contrary, Rachel Cleetus from the Union of Concerned Scientists denounced the “appalling” text: With “a paltry climate finance offer of $250 billion annually, and a deadline to deliver as late as 2035, richer nations including EU countries and the United States are dangerously close to betraying the Paris Agreement. This is nowhere near the robust and desperately needed funding lower income nations deserve to combat climate change. The central demand coming into COP29 was for a strong, science-aligned climate finance commitment, which [the text] utterly fails to provide.”

What now?

On the ground, a palpable lull can be felt; delegates look weary, the hallways are quiet, and protests in their frequency and turnout have thinned. This is in contrast to the tension and energy both in the press center and at the negotiating table.

Whether the text will be adopted is unknown, as is what these incoming “revisions” will look like. The word on the ground is that ministers are saying “no deal is better than a bad deal.”

One thing that is certain is that negotiations will yet again extend past their scheduled end.

The Magazine of The Sierra Club

The Magazine of The Sierra Club