Concerns About Infrastructure and Lack of Indigenous Representation at COP30 Abound

The next UN Climate Change Conference will follow this year’s stagnant negotiations on funding global adaptation

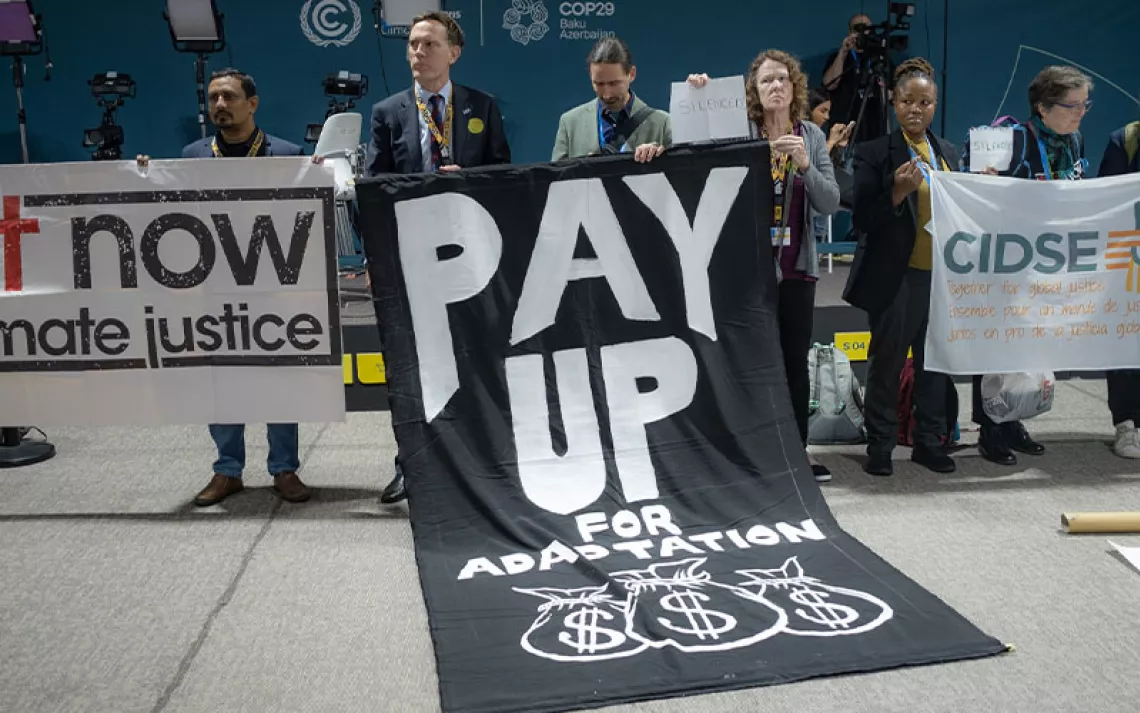

People demonstrate at COP29 on November 16 in Baku, Azerbaijan, where negotiations on funding global climate adaptation stalled out and came up short. | Photo by Peter Dejong/AP

When Brazil’s Belém was declared the host of the 2025 United Nations Climate Change Conference (COP30), it seemed like a natural choice. The South American country is home to nearly 60 percent of the continent’s Amazon rainforest—a carbon sink that plays a pivotal role in removing carbon dioxide from the atmosphere and home to 10 percent of all recorded wildlife species on Earth—and Belém is at the heart of it. The city of 1.3 million will act as a window into some of the issues on the climate conference’s agenda that also affect forest residents every day: forest and biodiversity preservation, climate change adaptation, climate justice, financing for developing countries, the reduction of greenhouse gases and the use of renewable energy.

But whether it’s up to the task is debatable.

Brazil has previously hosted an environment-focused UN conference. The 1992 Earth Summit, where the UN Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC) was established, took place in Rio de Janeiro. A major milestone in worldwide climate debates, the UNFCCC later led to two crucial treaties: the Kyoto Protocol and the Paris Agreement.

Expectations of success of that magnitude in Belém are low following the stagnant negotiations at COP29, and so are hopes that the Amazonian city will be prepared to host such a large number of visitors in just one year’s time.

Some 60,000 to 75,000 people are expected to attend COP30, and the federal government announced an investment of $4.7 billion Brazilian reais ($815 million) in transportation, accommodation, and venues earlier this month, with the promise that Belém will be able to “transform itself” to play host. “There’s no doubt it will happen,” said Wendell Andrade, a public policy specialist at the Talanoa Institute, an independent Brazilian think tank dedicated to climate policy. “But the conditions that people will see during those two weeks won’t be the same as they would be in a European city, or even in São Paulo.”

While hotel capacity, airport infrastructure, urban mobility and security for heads of state are all part of a long list of concerns related to Belém’s readiness for COP30, experts say the lack of provision of basic necessities for residents of the capital of Pará and other towns in the northern state is a much more pressing issue.

Belém is still among the top 10 cities in the country with the worst rates of basic sanitation, lacking in clean drinking water, sewage collection and treatment, drainage and management of rainwater, and urban cleaning, garbage collection, and disposal. According to the nonprofit Trata Brasil Institute, in Pará 91 percent of the population doesn’t have proper sewage collection where they live and just 2.38 percent of what is collected is treated. The city has the third-highest school dropout rate of any capital in Brazil and despite Belém's location in the Amazon, Brazilian statistics bureau IBGE notes that it has one of the lowest rates of trees planted along public roads, known as afforestation.

“Unfortunately, the local population is, as usual, being left out,” says Andrade.

So is the legacy of Pará. The government is eager to highlight the importance of the state’s rich biodiversity and place in Brazil’s economy—it leads agricultural production in the country’s north and is Brazil’s biggest producer of açaí, cocoa, pineapple and manioc. But its history with extractive industries (it was home to Serra Pelada, the world’s largest open-air mine, from 1980 to 1992, and is still one of the states most ravaged by illegal mining, at almost 370,000 acres) and long-standing history of being the Amazonian state with the highest rate of deforestation are being swept under the rug.

“Pará has one of the highest rates of environmental destruction, as well as one of the highest death rates of environmentalists trying to protect the forests,” said Beto Marubo, an Indigenous leader and member of the Union of Indigenous Peoples of the Javari Valley, citing as an example Sister Dorothy Stang. The American nun was killed in the Amazonian state in 2005 following death threats from loggers and landowners who were against her outspoken efforts to protect the rainforest and those who live in it.

“Even more important than the physical, economic legacies [of COP] is the legacy of the concept of climate change and how we should adapt our cities to these changes that we can’t avoid anymore.”

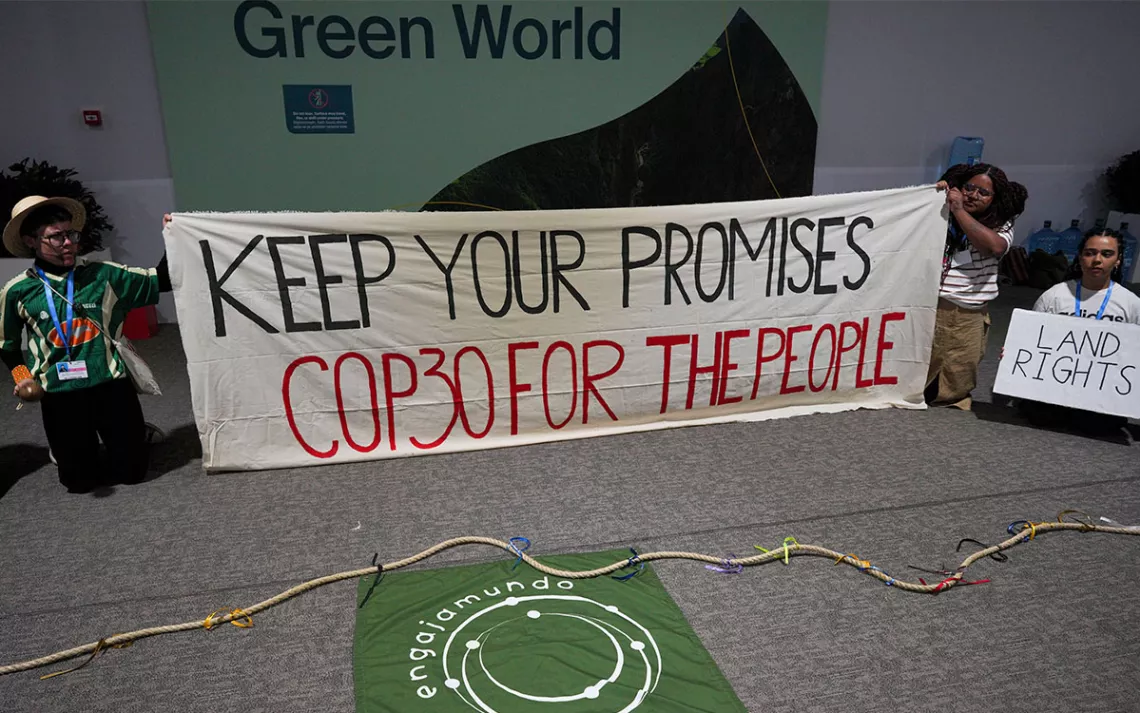

Indigenous activists who speak out against deforestation and illegal activity in the Amazon are also under constant threat, and many meet the same fate as Stang, including Tymbektodem Arara, who was found dead last year just two weeks after raising the alarm about illegal invasions of the Cachoeira Seca Indigenous Territory in the south of Pará. Experts have deemed the place of Indigenous people at COP30 essential, but despite reassurance from Brazil’s Indigenous Peoples Minister Sonia Guajajara that the conference will allow Indigenous peoples to “be in the negotiating rooms,” in order to enable “leaders to assist and subsidize” Indigenous causes, environmental activists and Indigenous people themselves have doubts about the quality of the participation that will be allowed.

“It’s the difference between necessary and sufficient,” said Andrade, noting that COP30 organizers have invited Indigenous, riverine, and quilombola people into discussions about preparations for the event, but not in a way he considers legitimate. “Calling on one or two Indigenous people to participate in four, five, six meetings doesn’t mean you can tell the world that the many and varied Indigenous populations are being heard.”

Being heard isn’t something Marubo even expects to come from the conference.

“We are conscious that actual decisions will not depend on what we say or what we protest. That will be up to the heads of state and representatives of each country," he said. "But we do hope that the discussions are, at the very least, efficient and transparent.”

The government’s focus on leaving the region with economic legacies, such as the announced infrastructure projects, has also left Andrade concerned that the point of the climate conference is being missed.

“Even more important than the physical, economic legacies is the legacy of the concept of climate change and how we should adapt our cities to these changes that we can’t avoid anymore,” he said. “It’s a central theme that should be discussed in cities across the Amazon. And now, this is the perfect time to highlight these issues, to teach children, to make better public policy decisions, to communicate with the population, and to educate citizens in general. But none of that is happening.”

Nor is progress on climate adaptation and the need for funding for adaptation, the main focus of COP29, the predecessor to Brazil’s upcoming event. Developing and developed countries were left butting heads at the negotiation table, and key questions—how much funding is needed, who should pay, and where that funding will come from—went unanswered, another item to be addressed at COP30.

Strides to keep the promise of nearly 200 countries at COP28 to transition away from fossil fuels also haven’t happened, with the burning of coal, oil, and gas hitting a record high this year. Brazil has promised not to “shy away” from the subject at COP30, despite being Latin America’s largest oil producer, but climate activists have called the country’s bluff, saying it hasn’t done enough.

Looking ahead to COP30, a decade after the conference that brought the world together under the Paris Agreement, there is concern that what little has been gained from the accord will be walked back. The US is the second-largest carbon emitter in the world, after China, yet US president-elect Donald Trump has called global warming a “scam.” His campaign promises include repealing major climate policies passed during Joe Biden’s presidency and returning to the same path that led him to withdraw the powerhouse country from the international climate accord during his first term as head of state.

“At COP30, we’re going to have an intense debate about the implementation of the climate goals being presented now,” said Andrade. “But any negotiation where the US … is not at the table is a negotiation doomed to be unambitious.”

The Magazine of The Sierra Club

The Magazine of The Sierra Club