At COP29, US Climate Congress Changes Tune

With a president-elect bent on dismantling climate gains, US climate allies reach for economics

At COP29, the US has a comparatively tiny “center,” frequented by few people. Biden is missing from negotiations, and the country's involvement is overshadowed by Trump’s desire to expand the fossil fuel industry and rescind unspent funds from the Inflation Reduction Act. | Photo by Nour Ghantous

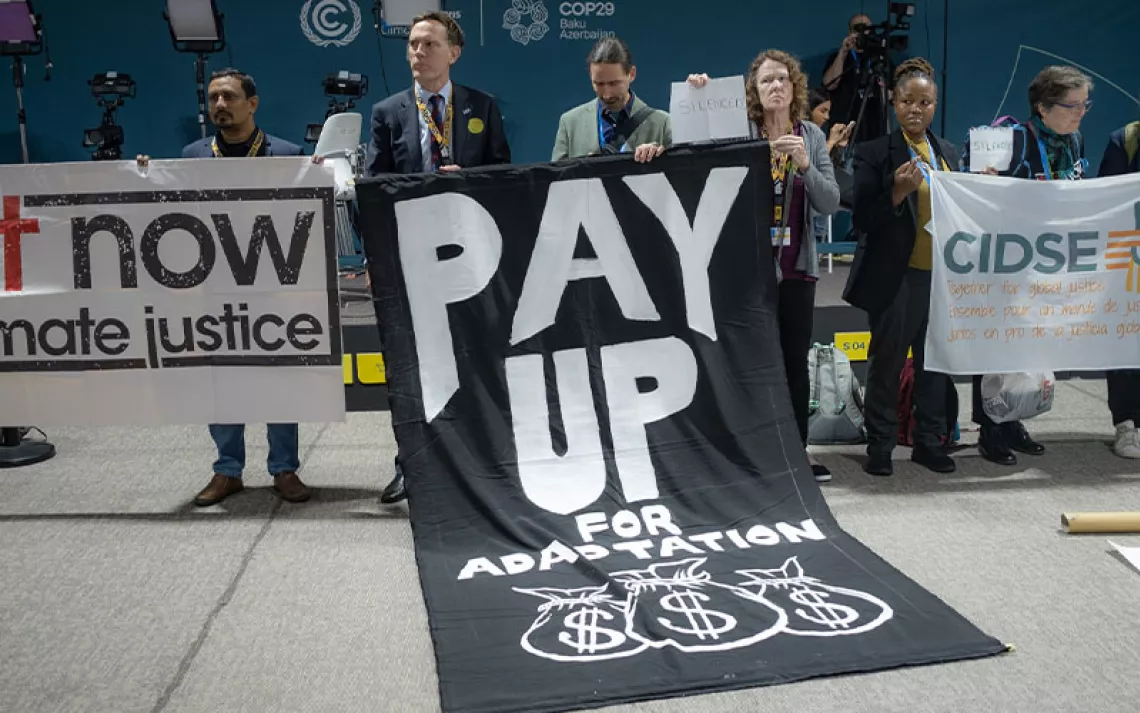

Tail between their legs, the United States’ climate leaders arrived in Baku, Azerbaijan, this week to take part in negotiating the financing of climate action at this year’s UN Climate Change Conference (COP29). Against the backdrop of President Joe Biden’s predecessor preparing to take office once again—as a staunch climate skeptic and fossil fuel proponent—the US delegation’s message and credibility appeared to hang in the balance.

On one side, the US delegation has substantial achievements to lean on. Biden’s Inflation Reduction Act (IRA) set a new standard for global climate action, inspiring major emitters to create their own ambitious climate packages. One example is Canada, which recently implemented its own climate action policies aimed at cutting emissions and boosting renewable energy, mirroring the IRA’s initiatives. Domestically, the IRA expanded economic opportunities across American society while mapping out a pathway toward tangible and near-term emissions reductions. Biden had set the ambitious 2030 target of cutting US greenhouse gas emissions by 50 to 52 percent below 2005 levels. This target, among others, is intended to help the US meet its obligations under the Paris Agreement and to push for global accountability on climate action.

Yet president-elect Trump has openly pledged to rescind unspent funds earmarked for the IRA, expand domestic oil and gas licensing, and withdraw a second time from the Paris Agreement (during his first term in office, Trump kicked off the withdrawal process in 2019; in 2021, the US rejoined the agreement after Biden initiated the move on his first day in office). This poses a stark contrast to the historic role the US played as an architect of the 2015 Paris Agreement, which commits 195 signatory countries to submit national emissions reduction plans and report progress. The agreement also calls on wealthier nations to fund climate projects, a key focus of this year’s conference.

With Trump’s return to the presidency looming on January 20, international delegates are anxious, questioning what this could mean for global progress—and looking to the US delegation for answers.

From moral imperative to economic incentive

At COP29, the messaging from climate allies of the US to the country’s successor government has noticeably shifted from an emphasis on the moral imperative of decarbonization to the economic rewards of climate action. Though much of this talk has revolved around the immediate value lucrative clean energy investments afford, the thought reverberates all the way to the cost efficiency of mitigating climate disasters that are expensive to clean up.

Conversations on the ground have echoed support for this sentiment, particularly with a lens on the shortcomings of Biden’s 2024 campaign. Many argue that his campaign could have garnered broader support by highlighting the financial benefits of the IRA rather than solely focusing on climate issues. After all, the IRA has created a strong economic case for clean energy that resonates across political lines: 85 percent of new projects and 68 percent of jobs the IRA created are concentrated in red states. Among the top 20 congressional districts for clean energy investments, Republicans hold 19.

IRA-funded projects will generate nearly 110,000 new jobs and bring at least $126 billion in private investment to 40 states, found a report by US advocacy group E2. It notes that currently over 110 major clean energy and EV manufacturing plants are in development, with 55 of them located in the Republican-led states of South Carolina and Georgia.

Global climate allies seem to hope that the financial benefit of the IRA will ultimately be too great an incentive for the incoming Trump administration to pass up.

The states may take the reins

Despite the very real financial gains to be had, under Trump—who has consistently and falsely called climate change a “hoax” for many years—it may increasingly fall to states to fill a federal leadership gap on urgent climate action at home and globally. At COP, California’s secretary for environmental protection, Yana Garcia, defended her state’s climate efforts on stage alongside British journalist Nik Gowing.

“The next few months to a year will be very telling in terms of what this federal administration will do—if the last federal administration is any indication of what’s to come, we’ll certainly be filing a lot of lawsuits,” she warned.

When asked about the impact of the election on US climate commitments, Garcia countered the notion that progress is at risk, calling it a “damaging narrative.” She vowed to continue championing California’s environmental agenda “regardless of who occupies the White House” and said it would be a “deep mistake” for Congress to dismantle the IRA, which she said represents undeniable economic opportunities.

Sign up to receive Sierra News & Views

Get articles like this one sent directly to your inbox weekly.

With this action you affirm you want to receive Sierra Club communications and may vote on policy designated by the Sierra Club Board.

According to the last available data from 2020, California alone does have a significant role to play in lowering total emissions from the US: It is the second-highest greenhouse-gas-emitting state in the US, trailing only Texas, accounting for 6.6 percent of total national emissions. California is also among the states hardest hit by the outcomes of climate change, grappling with extreme heat, devastating wildfires, water pollution, and the worst air quality in the nation.

Weathering changing political winds

“The federal government’s policy will be determined by the next administration, and we’ll all stay tuned to that,” Biden’s White House climate advisor Ali Zaidi told Sierra at COP29, following an event on actualizing net-zero ambitions. “Now what I’m confident of is that states and cities, the private sector, and American workers are recognizing the massive economic opportunity that’s in front of us and are eager to chase it.”

As the US delegation at COP29 navigates the challenge of communicating a climate strategy that endures among changing political winds, it is, like its allies, pushing the argument that the financial rewards from clean energy investments are too significant to be undone. The message is clear: Dismantling the IRA would not only harm US environmental commitments but would also undercut economic opportunities for American workers and businesses.

When asked what he’d say to the next White House climate advisor, Zaidi told Sierra: “We have unlocked, in this massive crisis, a way to expand our manufacturing capacity, lift up communities that have been left behind, and deliver clean air and clean water to the American people. This is the essential task of our time to deliver on, for those who send us to Washington to serve.”

This shift from climate morality to economic pragmatism offers a compelling counter to the prospect of Trump’s rollback of climate progress. The IRA’s impact extends beyond emissions reductions to job creation, community investment, and international influence, with the hope that these outcomes might endure beyond the current administration.

As delegates in Baku look on to the second week of this crucial conference, the future of American climate policy remains a pivotal issue—one that could shape the direction of global climate action and finance for years to come.

The Magazine of The Sierra Club

The Magazine of The Sierra Club