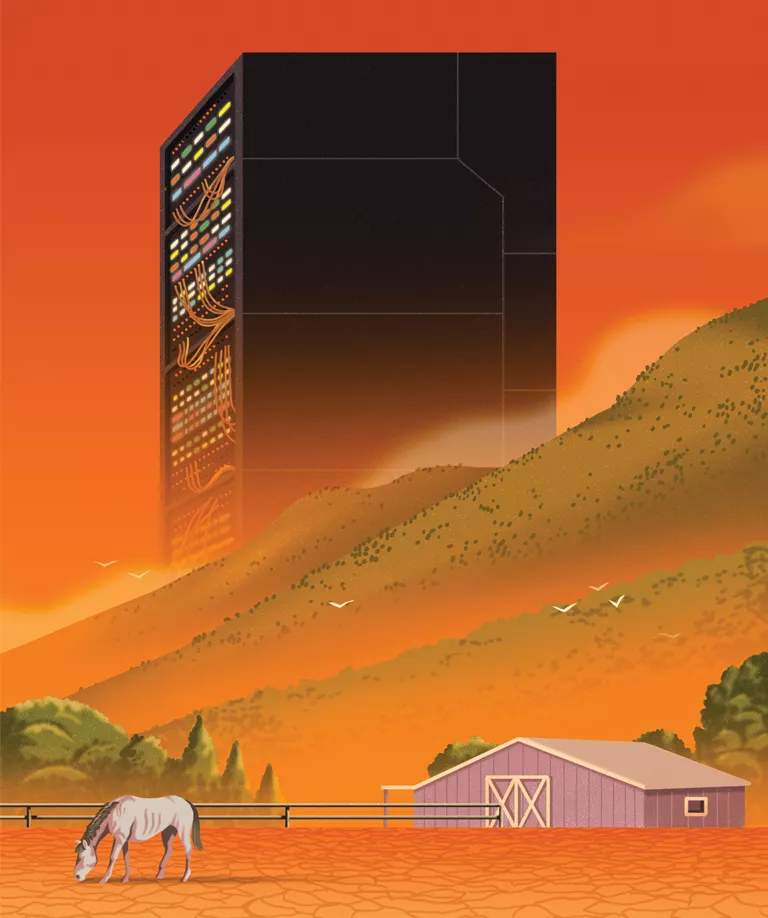

Here's What Happens When Big Data Takes Over a Small Town

In Virginia, the planet's largest proposed data center threatens local ecosystems

The pastoral landscape surrounding Manassas, Virginia, has been eyed by developers for decades—plans have been drawn up and then dashed for a shopping center, an interstate, even a Disney theme park. Despite these pressures, much of the region has retained its rural character. Butterflies visit clumps of wildflowers. Turkeys and deer stamp out muddy trails. Foxes dart in between clearings as they traverse the region’s forests.

It’s no accident that this bucolic scene of rolling hills, two-lane roads, and horse pastures still exists just 20 miles from downtown Washington, DC. In 1998, the Prince William Board of County Supervisors adopted a comprehensive plan to protect the area from the tentacles of urban sprawl creeping from the nation’s capital.

But no one foresaw the threat that booming technologies like cryptocurrency and artificial intelligence would pose to this rural enclave. Data centers already occupy 8 million square feet of space in the county. If all the proposed new data centers are built, that number could balloon to 80 million. Some advocacy groups predict that the amount of electricity these centers would need is enough to power five New York Citys.

One project in particular is accelerating that growth. In a December 2023 meeting, the board of supervisors approved the largest data center campus on the planet, a project called Digital Gateway, which will include 23 million square feet of data center space across 2,100 acres of former farmland. The energy to run such a ginormous facility could require about 750,000 homes’ worth of electricity, according to the National Parks Conservation Association. Owing to a lack of renewable energy, much of that will come from fossil fuels.

A large data center can guzzle up as much as 5 million gallons of water a day, the equivalent usage of a town with 50,000 people.

In terms of harm, the construction of this facility—on land next to Manassas National Battlefield Park—will be a twofer, undermining the state’s goal to decarbonize the electrical grid by 2050 while also obliterating wildlife habitat. The twin threats have sparked opposition from local and national environmental groups, which are increasingly focused on the adverse effects of a growing information economy.

“What do we genuinely want our society to look like 100 years from now?” asks Kyle Hart, a program manager for the National Parks Conservation Association, which opposed the project.

Now only a couple of lawsuits and the determination of conservation advocates stand between these pastoral panoramas and Digital Gateway. While the lawsuits—which hinge on whether the county provided proper notice of the board meeting—wind their way through court, the newly formed Virginia Data Center Reform Coalition has asked the state government to step in and prevent projects like Digital Gateway from being green-lighted again. Made up of more than 25 organizations, including the Sierra Club’s Virginia Chapter, and homeowners’ groups, the coalition thinks the state can do more to reduce the impacts on the surrounding community and ecosystems.

“We need statewide reform,” says Julie Bolthouse, director of land use for the Piedmont Environmental Council and a co-organizer of the reform coalition with Hart. “We can’t do this Whac-a-Mole. We’re not winning a single data center battle.”

Northern Virginia’s zoning laws are partly to blame. The first data center in the region was built in the early 1990s by America Online. Bearing little resemblance to today’s monstrosities, it was integrated into an office park along with shops and restaurants. “It was honestly really desirable,” Bolthouse says. So desirable that many counties in the region implemented “by right” zoning for data centers, requiring boards to approve applications as long as the centers satisfy a few basic conditions such as height and size requirements.

Today the AOL campus is a pile of rubble on its way to becoming another hulking center in the middle of what’s known as Data Center Alley, a cluster of nearly 300 centers that together host 70 percent of the world’s internet traffic. In tandem with generous tax breaks, the area’s zoning laws have resulted in the construction of data centers adjacent to schools, nursing homes, and housing developments.

They’re why the Tippet’s Hill Cemetery, an active and historic African American burial ground—with headstones dating back to 1863—is now surrounded on three sides by data centers. They’re why joggers on the area’s popular rail trail now take in views of diesel generators during their morning miles. They’re why many residents of Village Place, a tidy neighborhood in the once-rural town of Gainesville, look out their bedroom windows to see the yawning gray walls of a data center.

Hart and Bolthouse are clear: The reform coalition isn’t calling for a moratorium on data centers in Northern Virginia but rather a more circumspect and transparent planning and approval process—especially when it comes to power usage. “There should be a requirement that these impacts are covered by the industry,” Hart says. The coalition is petitioning the state to mandate that data center developers pay for their own energy needs—or, ideally, run their facilities on renewable energy.

In addition to their energy needs, data centers require water for evaporative cooling systems that keep servers from overheating. A large data center can guzzle up as much as 5 million gallons of water a day, the equivalent usage of a town with 50,000 people. Data centers that power AI applications need even more water. For every 50 questions it’s asked, ChatGPT requires the equivalent of a 16-ounce bottle of water. In Virginia, some developers have requested permission to tap the county’s groundwater for their cooling systems.

Proponents of the data centers argue that the burden on ratepayers and the drain on natural resources is a small price to pay for the tax revenue pouring into the county’s coffers—money that can be used to improve public schools and aging infrastructure. But Hart argues that relying on tax revenue from data centers sets a dangerous precedent. “When your county is the data center capital of the world, your budget becomes so dependent on that tax revenue that you almost have to keep new systems in the pipeline to keep feeding the monster,” he says.

Depending on how the lawsuits shake out, in a few years, visitors to Manassas may find themselves in a construction zone, where dump trucks and jackhammers are the soundtrack to an afternoon hike. Or maybe not. Thanks to the tireless work of conservation advocates so far, the turkeys and foxes and wildflowers of Prince William County still have a home.

The Magazine of The Sierra Club

The Magazine of The Sierra Club