The Right to Repair Is Essential to Reducing Electronic Waste

An excerpt from the new book "Power Metal: The Race for the Resources That Will Shape the Future"

Photo by Westend61/Getty Images

Excerpted from Power Metal: The Race for the Resources That Will Shape the Future, by Vince Beiser, published by Riverhead Books, an imprint of Penguin Publishing Group, a division of Penguin Random House, LLC. Copyright © 2024 by Vince Beiser.

It didn’t seem like a life-altering event when Kyle Wiens accidentally dropped his Apple iBook off his dorm room bed one day in 2003. The laptop landed on its corner where the plug connects to the machine, and when Wiens picked it up the little light indicating that electricity was flowing into the computer was dark. Wiens guessed the problem was a loose wire or broken soldering joint, something that should be pretty easy to fix. He was a handy guy, an engineering student at California Polytechnic State University in San Luis Obispo. His grandfather, who had attended the same school years earlier, had given him a soldering iron as a present when he left for college for just such small repairs.

Wiens tried to open up the machine and take it apart. He was confounded almost right away—there were all kinds of small tabs and latches and the whole apparatus was bafflingly complicated. Wiens had worked in an Apple store in high school, so he knew there were repair manuals that could walk him through what needed doing. He tried hunting one down on Google, but to his astonishment, couldn’t find one.

So he just winged it. With the help of a friend, Luke Soules, he took the machine to pieces on his dorm room floor. It took them two days, and they lost a few screws and broke a few latches along the way, but they finally managed to find the broken connection and mend it with a drop of fresh solder. They put the computer back together, and it worked fine.

“Why was that so hard?” Wiens wondered. Why couldn’t he find anything online about how to repair his laptop? He did more research, and learned that the problem wasn’t that nobody had made Apple repair manuals available on the Internet. The problem was that websites that had posted such manuals had been ordered to take them down by Apple. In other words, one of the world’s biggest companies was actively working to make it harder for its customers to fix its products.

“That really pissed me off,” Wiens says. “The idea that this information was forbidden fruit did not sit well.” He’d paid good money to buy his computer from Apple. It wasn’t theirs anymore. It was his. Why shouldn’t he be able to fix it?

It was time, Wiens decided, to fight for his rights. Specifically, his right to repair.

Sooner or later, all electronic products will stop working. Some part will get fried, some internal system will slip out of whack. Entropy will inevitably collect its due. What do you do then? If the product in question is a car, no one would answer, “Recycle it and get a new one.” Recycling that car would mean tearing it to pieces, separating out the plastic and glass and metals that it’s made of, then smelting those down so they can be sold back into the market. Recycling any electronic product similarly means extracting all the constituent materials of that highly engineered product and reverting them back to their original state—their most basic, literally elemental form. By and large, recycling is the most inefficient, most labor and energy-intensive method of getting further use out of just about any given product.

When it comes to a malfunctioning car, most people start by trying to repair it. You can do that yourself, or take it to the dealer you bought it from, or to an independent repair shop. When it comes to a whole range of smaller products, however, everything from lamps to vacuums, it’s not nearly as common or easy to fix them when they break down. And especially when it comes to digital devices like phones, tablets and laptops, the default is: when it breaks, just replace it.

This is no accident. It’s the result of deliberate corporate strategy. It was that strategy that Wiens set out to battle.

The most obvious reason to fix an electronic product (or any product, really) rather than replace it is simple: Repair is usually cheaper. To that personal-level motive, add a planet-level one: the more electronic products that have their lives extended by repair, the fewer natural resources and the less energy needed to manufacture new electronic products. The imperative to fix things, writes journalist Aaron Perzanowski in The Right to Repair, “grows out of a recognition that resources are finite, that the planet is small, and that a culture that overlooks those facts imperils its future. Repair allows us to extract maximum value from the artifacts we create.”

Each broken cell phone or hair dryer contains only small amounts of copper, nickel and other metals, but keeping millions or billions of them in use obviates the need for huge amounts of mining. It took something like 75 pounds of raw materials to manufacture your phone, generating heaps of waste in the process. Digging all that material up burns a lot of energy, too, generating greenhouse gases. In his book Electrify: An Optimist’s Playbook for Our Clean Energy Future, engineer and MacArthur “Genius Grant” recipient Saul Griffith analyzed the energy used and carbon emitted per kilogram of a range of products. His conclusion: “To reduce environmental impact, you can lower the weight of a thing, or you can use a different material altogether. But making the thing last longer is key.”

Extending the lifetime of all the smartphones in the European Union by just one year would prevent the release of 2.1 million metric tons of carbon dioxide per year by 2030, according to a study by a consortium of European environmental groups. That’s the equivalent of taking more than a million cars off the roads.

Wiens and Soules launched their crusade by writing their own laptop repair manuals and posting them online. The response from consumers was enthusiastic. “We got like 30,000 hits the first day,” Wiens says. They branched out into other products, and soon a dorm-room business dubbed iFixit was born. By the time he graduated in 2005, Wiens decided to try making a career of it.

Today, from its base in San Luis Obispo, California, iFixit hosts a free online repository of more than 98,000 DIY repair manuals for some 47,000 separate products, from the iPhone 15 Pro to the Black and Decker Pet Vacuum. Some were written by staff members, many by volunteers. Millions of people visit the website every month. The company makes money selling tools and replacement parts, and from consulting services. Wiens declines to share revenue numbers, but there’s enough cash coming in for him to employ about 170 people.

“Our mission is to teach everyone to fix everything,” he says. “We want to make it easy to share knowledge and simple to do repairs.” To do that at scale, however, Wiens decided it wasn’t enough to rely on individuals figuring out solutions and sharing what they learned. He wanted to force the corporations that make that gear to help. Or at least, to stop making it harder.

“It takes something like 75 pounds of raw materials to manufacture your phone, generating heaps of waste in the process.”

What’s good for consumers and the planet is not always good for corporations, of course. Apple makes money if you buy a new iPhone; it makes nothing if you get your old iPhone fixed at an independent repair shop. That’s why companies of all sorts have for decades discouraged repair and encouraged customers to instead buy the newest, latest thing. As far back as the 1920s, Ford and General Motors began introducing new car models each year, with the explicit intention of getting drivers to trade in their functional but no longer fashionable older flivvers. “Planned obsolescence” was celebrated as a tool to keep the consumer economy humming.

America’s burgeoning wealth helped undermine the practice of repairing things. “In the nineteenth century, and well into the twentieth,” writes Adam Minter in Secondhand, “thrift wasn’t a matter of choice or virtue. It was a necessity. The essentials of daily life—clothes, kitchenware, tools, furniture—were expensive and intended to last for years, if not lifetimes. Repair was a way to ensure that they did.” But as Americans got richer and manufacturing got cheaper, fixing increasingly fell out of fashion. In 1966, according to Perzanowski, some 200,000 Americans worked as home appliance repairers; by 2023, that number had dropped to about 40,000. The world of digital gear is on the same trajectory. The number of electronic and computer repair shops in the United States dropped from 59,200 in 2013 to 45,830 in 2023.

Ironically, it’s often much easier to get electronics fixed in developing countries than in rich ones. In nations across the global South, where many people subsist on just a few dollars a day, “the essentials of daily life” are still expensive and worth repairing. I saw this first-hand in the Ikeja electronics market in Lagos, Nigeria. The place teems with tiny kiosks and elbow-to-elbow stalls where tradesmen will replace a broken phone screen or swap a new hard drive into your laptop while you wait. They’re not certified by any big corporations, but their skills are top-notch. Lagos is particularly renowned for the quality of its electronics repair workers, but you can find people doing the same work in cities from Delhi to Cairo—everywhere people don’t have the wasteful luxury of constantly buying new electronics.

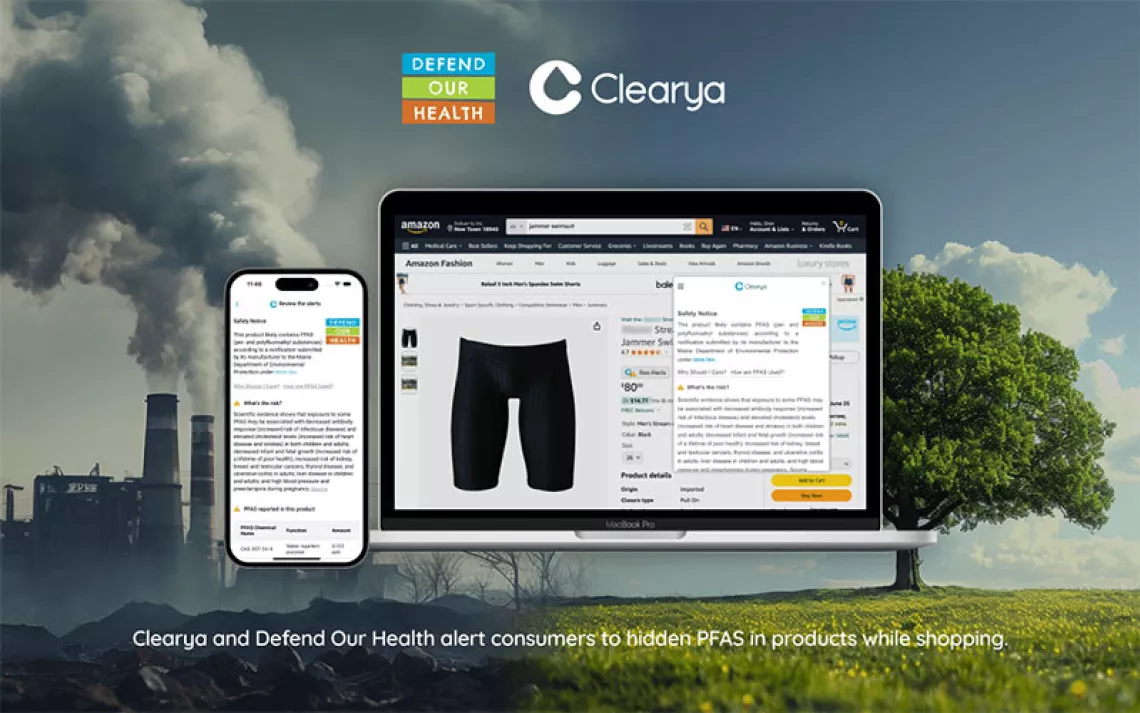

This is not entirely the fault of affluent consumers. The electronics industry deliberately makes their products difficult to repair. Take a look at your cell phone, tablet or laptop. Chances are there is no easy way to even open it up to see its components, the way you can pop a car’s hood, let alone swap in a new battery the way you can with a flashlight. That’s by design. Frequently broken parts like cell phone screens are held in place with glue, making them hard to remove without damaging the phone. Other parts are fastened with unusually-shaped screws that require special screwdrivers. Manufacturers deliberately discourage DIY repairs with claims that they are unsafe or will void the product’s warranty.

“The 2019 iMac manual cautions that ‘Your iMac doesn’t have any user-serviceable parts, except for the memory…Disassembling your iMac may damage it or may cause injury to you,’” writes Perzanowski. “Apple offers similar warnings to iPhone owners, who are told in no uncertain terms ‘Don’t open iPhone and don’t attempt to repair iPhone yourself.’” Local fix-it shops are also hamstrung. Parts, manuals, and necessary software are often made available only to high-priced authorized service providers.

By the early 2010s, Wiens had decided that the only way electronics companies would change their ways was if they were forced to. So he shifted from publishing manuals into political advocacy. Ever since, Wiens and other activists have been lobbying local, state and federal legislators to enact “right to repair” laws that would obligate manufacturers to make manuals, tools and parts available to everyone. Similar rules already cover automakers; that’s why you can take your balky Volkswagen either to an official dealer or an independent local shop.

Well over one hundred right-to-repair bills were introduced in state legislatures in the 2010s. Every single one of them was shot down.

It wasn’t exactly a fair fight. On one side were Wiens, local activists and consumer advocacy groups; on the other was Apple, Microsoft, Amazon, Google, Tesla, T-Mobile and other giant corporations, all of which have lobbied against Right to Repair bills. “The industry was able to sow a lot of FUD—that’s fear, uncertainty and doubt,” says Wiens, who has testified in support of dozens of these bills. “I have a lot of sympathy for these state legislators because they have so many complex issues coming across them all the time, and then they have Apple come in and say, ‘If you do this thing, you'd be the first state ever to do it and that will disrupt all commerce in America.’ You don't want to be the person who screwed up the technology industry in the US.”

“The more electronic products that have their lives extended by repair, the fewer natural resources and the less energy needed to manufacture new electronic products.”

Manufacturers argued that their restrictions were necessary to safeguard trade secrets, and to protect people from hurting themselves by messing with their machines. “Apple told Nebraska lawmakers that the bill would turn the state into a ‘Mecca for bad actors,’ predicting that hackers and other nefarious figures would flock to the state to exploit consumers. And in California, it warned that consumers were at risk of physical injury if they attempted to swap out their iPhone batteries. Wahl cautioned that repair of its hair clippers could cause fires, while Dyson and LG issued unfounded warnings that the right to repair could put consumers’ personal safety at risk by allowing repair personnel in their homes who had not cleared background checks,” writes Perzanowski.

Apple CEO Tim Cook all but admitted the real reason in a 2019 letter to investors. The previous year, it had come to light that Apple had been deliberately slowing down the performance of some older iPhones. Customers were furious. In a bid to placate them, Apple temporarily reduced the price of an authorized battery replacement from $79 to $29. Some 11 million iPhone owners took the deal, giving their old phones a new lease on life. Result: sales of new phones dropped. That was a big problem for the company, since iPhone sales provide the bulk of Apple’s revenue. “ iPhone upgrades … were not as strong as we thought they would be,” Cook wrote, blaming in part “customers taking advantage of significantly reduced pricing for iPhone battery replacements.” The cut-rate replacement program was soon scrapped. As of 2023, Apple was charging $129 to replace a new iPhone’s battery.

But years of pressure from Wiens and others finally helped achieve a breakthrough. In 2021, the Federal Trade Commission published a landmark report that scrutinized all the tech industry’s objections to repair laws. Its authors concluded that device makers’ concerns could either be addressed with some modifications, or simply had no merit in the first place. “There is scant evidence to support manufacturers’ justifications for repair restrictions,” the report concludes tartly. “Although manufacturers have offered numerous explanations for their repair restrictions, the majority are not supported by the record.” President Biden soon followed up with an executive order that encouraged the FTC “to limit powerful equipment manufacturers from restricting people’s ability to use independent repair shops or do DIY repairs.” The following year, the FTC put some bite into its bark, fining Harley-Davidson and Westinghouse for illegally restricting customers’ ability to repair their products.

By then, the European Union had already adopted rules aimed at making it easier to repair home appliances, including requiring manufacturers to make spare parts available, and ensuring they can be replaced with common tools. The UK also rolled out regulations obliging electrical appliance manufacturers to make spare parts available to consumers.

Manufacturers have started to get the message. Since 2021, Motorola, Samsung and others have made a complete 180, and now allow independent repair shops access to parts and tools. Some are even partnering with iFixit to help customers repair their products. “They’ve shifted from being antagonists to business partners,” says Wiens. “They are not coming of their own free will,” he is quick to add. “It took getting to the point where it was clear that legislation was inevitable for the companies to come on board.”

Not that all of them did so with the best of grace. In 2022, Apple rolled out a self-service repair program. It posted online manuals for some of its products, and offered to send users the same set of tools used in the company’s repair facilities. That sounded good. But when a New York Times reporter tried out the service, he found that “it involved first placing a $1,210 hold on my credit card to rent 75 pounds of repair equipment, which arrived at my door in hard plastic cases. The process was then so unforgiving that I destroyed my iPhone screen in a split second with an irreversible error.” Critics called it “malicious compliance,” an effort designed to fail.

That same year, however, the American repair movement notched its first major victory. New York State actually enacted a “right to repair” law, which iFixit helped write, requiring manufacturers to make service information, parts and tools available to the public. Lobbyists from Microsoft, Apple and other tech companies managed to punch some big loopholes in it—the law covers only digital electronics, leaving out home appliances and many other devices, and applies only to machines manufactured after July 1, 2023. Still, says Wiens, “we were thrilled. It was a big moment.”

Momentum is growing. Several months later, Minnesota adopted a similar law. In October of 2023, California also passed one—with the surprise support of Apple. Someday soon, all Americans may have the freedom to fix.

The Magazine of The Sierra Club

The Magazine of The Sierra Club