Researchers Get Closer to Creating a Real-Life Jurassic Park

Could bringing back extinct species serve a real conservation purpose?

Human activities have driven nearly 500 species to extinction in the past century; more species will likely follow as habitat loss and climate change accelerate. Such tragedies unravel the web of biodiversity that is the foundation of healthy ecosystems. They also leave our world a depleted and lonelier place.

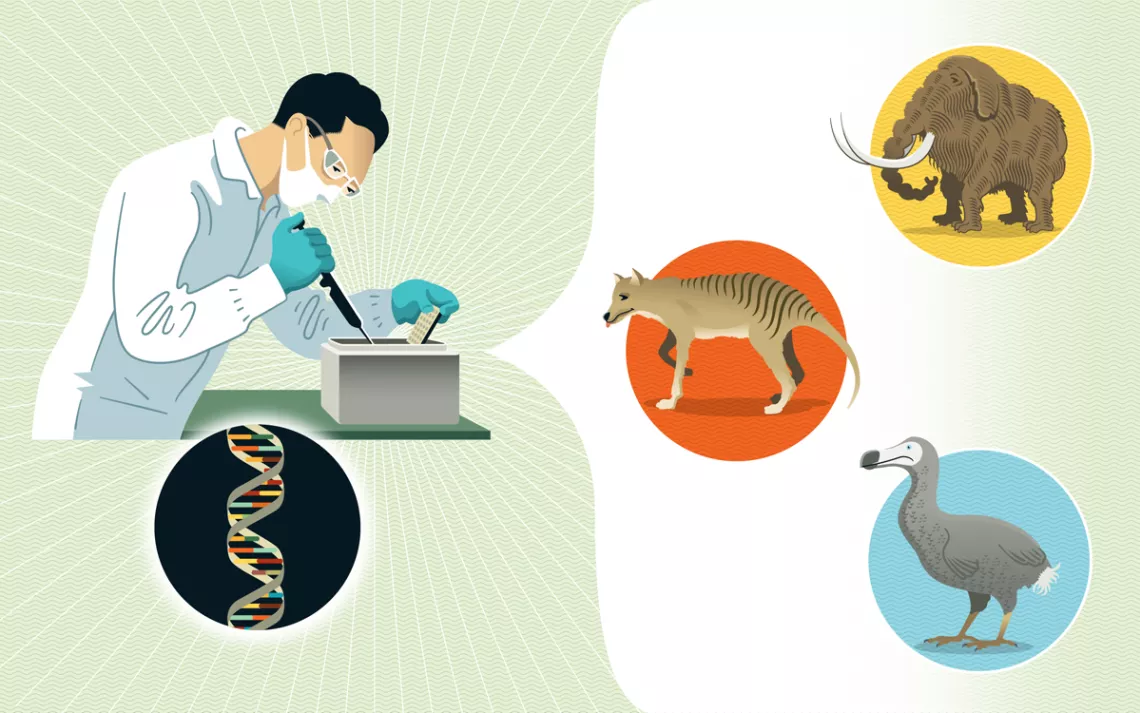

The moral and practical implications of such human-induced loss have led some researchers to pursue “de-extinction,” the idea that we can resurrect long-lost species. Some proponents of the effort say that society has a duty to atone. Others highlight its potential to revive the ecological functions of ancient lineages, as is the case with woolly mammoths, which researchers hope will help sequester carbon by trampling the ground and promoting new grass growth in the tundra. And some believe it could be a valuable tool for preventing future extinctions.

How it’s supposed to work

The goal of de-extinction is not to produce clones but instead to use genetic engineering to create proxies of extinct species that look and behave similarly. To do this, geneticists are trying to insert the traits of an extinct species into the genes of a living relative to create a hybrid. This is easier said than done. The extinct animals are no longer alive to confirm their adaptive traits. So researchers can only make educated guesses about their defining characteristics.

Here’s what de-extinction would look like for a mammoth: Researchers would study its genome and identify traits that helped it survive in the cold—fat deposits, thick hair, small ears. They could then use a gene-editing technology like CRISPR to insert those genes into the genome of an elephant, its closest living relative. The hybrid genome would be inserted into a nucleus, which would then go into the egg of a living elephant, where it would be fertilized.

What could go wrong?

Presuming that the technical gene-editing issues can be worked out, introducing species into areas where they don’t live, even if they lived there previously, is fraught with risks. It requires extensive evaluation of the potential ecological impacts, in-depth conversations with local residents, and cooperation among multiple levels of government. Already, efforts to bring back the dodo and the Tasmanian tiger have ignited complaints from local communities about their lack of initial inclusion in the plans.

The degree of genetic engineering needed also raises ethical and animal-welfare concerns. Even reintroductions of living animals are hard to pull off. When researchers in India reintroduced cheetahs, half of them died within the first year of their release. There is also little to no evidence that de-extinction would restore ecological processes as proponents say it will. In a worst-case scenario, an introduced “de-extinct” species could act more like an invasive species and harm the ecosystem rather than help it.

For conservation purposes, gene-editing tools developed through de-extinction research could be put to use to help endangered species, but it’s not clear what those tools would be, and they could also be developed by working with still-living animals.

The upshot

Even if proxy species that resemble and behave like extinct species can be created, successfully introducing them into the wild and building up a functional population would take many decades and is not guaranteed to have any environmental benefits. Given the current biodiversity crisis, we should be investing in efforts to protect species and ecosystems that are still alive rather than pursuing flashy vanity projects.

The Magazine of The Sierra Club

The Magazine of The Sierra Club