Art under the Microscope

Because Mother Nature is always ready for her close-up

By Chelsea Leu

December 22, 2014

Sure, nature’s vast expanses can blow our minds. But let’s not forget the little things. Here’s a peek into the world of photomicrography, the art of capturing the tiniest wonders of nature, and the photographers who make it their life’s work to show others what they see under their microscopes.

Above, grains of sand collected by Gary Greenberg from a sandy beach in Maui show the diversity of Hawaiian marine life, from shell fragments to sea urchin spines.

Gary Greenberg, sandgrains.com

A sweeping mountain vista on an inky night? Not quite. This photo’s field of view is actually a mere centimeter across, and it depicts the interior of a quartz crystal. The “mountains” are actually etch tubes formed when the crystal’s growth is interrupted. They look convincingly craggy, thanks to glints of light that reflect off an iron mineral staining the quartz’s inner surface.

Los Angeles-based photographer Danny Sanchez snaps gemstone inclusions—the tiny imperfections in minerals that become trapped during crystallization. The landscapes he finds in these tiny crystalline worlds recall ocean reefs or icicles.

Danny Sanchez

Field of view = 6.8mm

Of the opal in this photo, Sanchez writes: “The play of color captured within…appears to radiate upward from an alien landscape. In actuality, the spectral colors we see in opals are produced when light diffracts through tightly packed silica spheres.”

Sanchez is a gemologist, which sounds like a career straight out of a fairy tale. He began studying gemstones and minerals in his mid-20s, after an unfulfilling career as a musician. “Ever since I could remember,” he says, “I was fascinated with the way light behaved within objects.” Now, he works with gems and loves it, a passion that comes through in his work. “My photographs all started because I wanted other people to see what I saw through the scope,” he says.

Danny Sanchez

Field of view = 14.4mm

Sanchez calls this photo “Rutile Castle” for the craggy golden protrusions that rise up from hematite like turrets from a Bavarian palace.

When you’re working on scales as small as these, Sanchez writes, “everything vibrates: the fans in the light source, the computer on the floor, your music, the camera reflex, the car down the street.” Pressing the shutter manually is out of the question, so Sanchez uses computer software to control the camera. “It's super nuanced, maddening and cathartic,” he says, “and I love every second of it.”

To see more of what’s under Sanchez’s scope, check out his website and Tumblr.

Danny Sanchez

This is a close-up shot of sphagnum, or peat moss, a genus that dominates bogs in Scandinavia, Canada, and the United Kingdom.

When Polish photographer Marek Mis was thirteen, he found a copy of Paul de Kruif’s The Microbe Hunters in his father’s cupboard. He was taken by the work of van Leeuwenhoek, the pioneering 17th century scientist who built his own microscopes and discovered the existence of bacteria. Mis began constructing his own microscopes, and at first drew everything he saw in them. Eventually, he began taking photos with an old Smena 8M. These first photomicrographs were monochrome and not very good, he admits. He still has those early negatives.

Mis now photographs full-time, and his work has recently been recognized in the Nikon Small World photography competition. Apart from scientific documentary purposes, he says, “I always try to show the beauty of the micro-world.”

Marek Mis

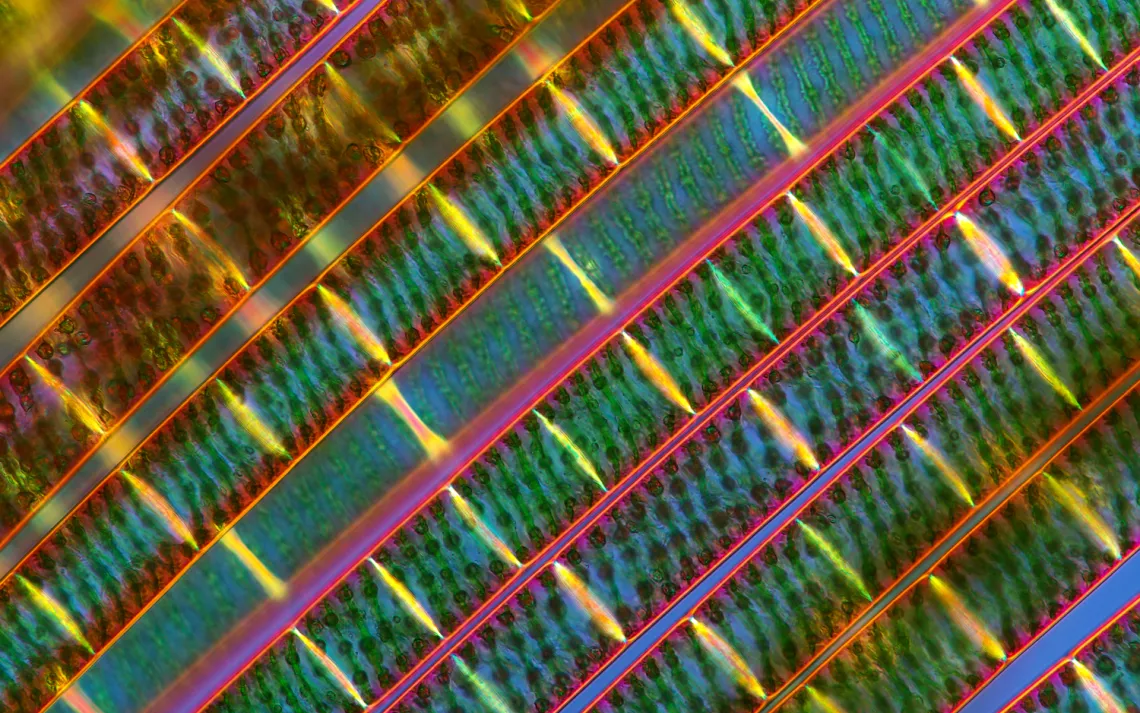

These strands are filaments of Spirogyra, a green algae so named for the helical chloroplasts wound up within its cells. These green squiggles are both beautiful and functional: they allow the algae to photosynthesize and grow in clumps in freshwater ponds.

Marek Mis

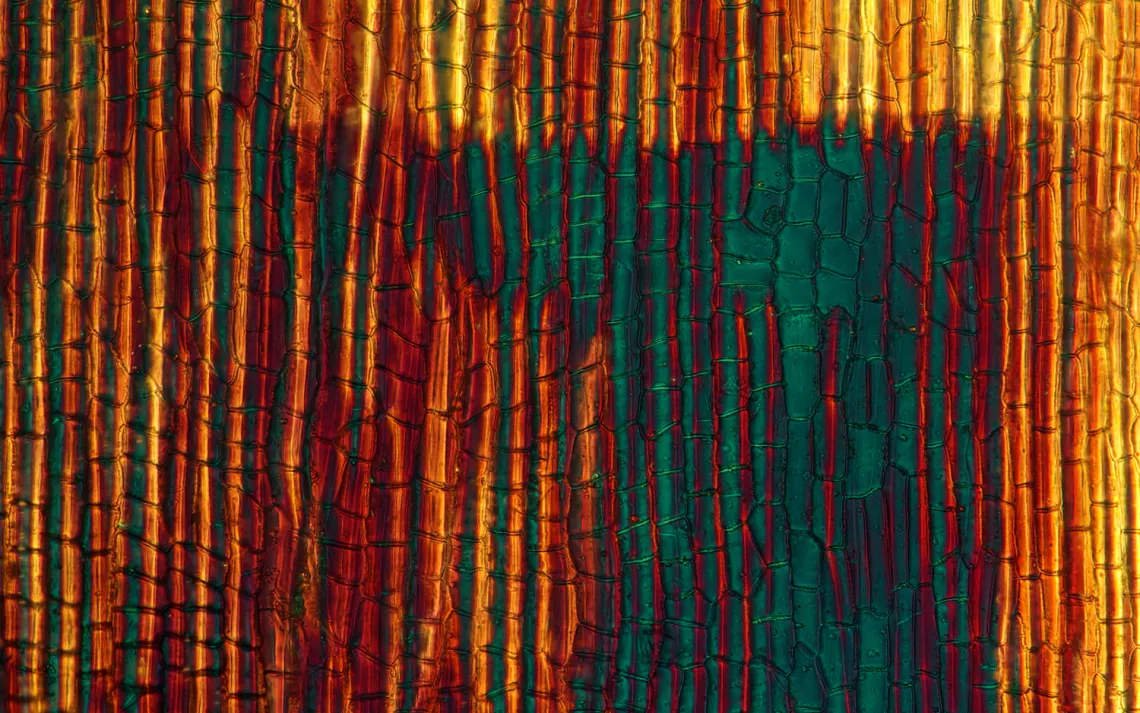

This photo wouldn’t look out of place among Rothkos at an Abstract Expressionist exhibit. But its subject is hardly abstract: it’s the tissue of an ornamental jewelweed (Impatiens glandulifera Royle), a touch-me-not flower native to central Asia and common in New England.

Marek Mis

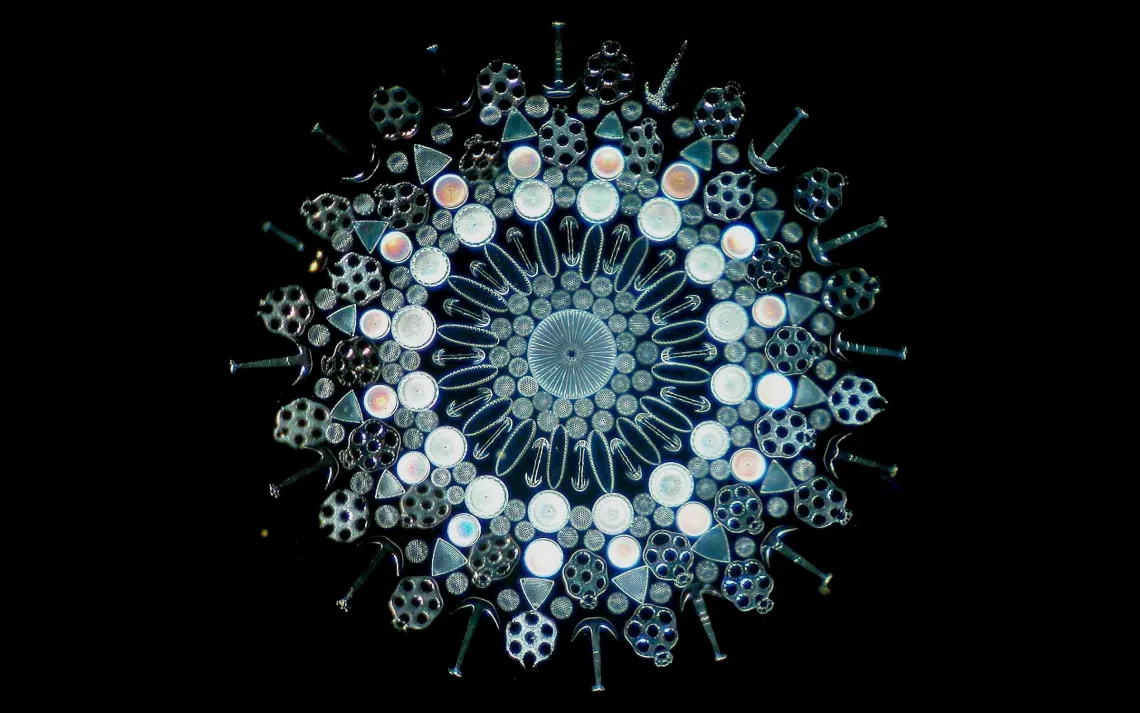

This microscope slide is from the collection of Howard Lynk, who studies and photographs Victorian-era curiosities. Say what you will about their rigid social mores and their propensity for fainting—the Victorians were also enthusiastic naturalists. Spurred by the development of the microscope, 19th-century Europeans would often collect tiny curiosities from the natural world. Using tweezers and boatloads of patience, these “diatomists” would arrange diatoms, sponge spicules, and sea cucumber ossicles into kaleidoscopic displays like this one.

For more microscope slides and fascinating historical context, check out Lynk’s website.

Howard Lynk, victorianmicroscopeslides.com

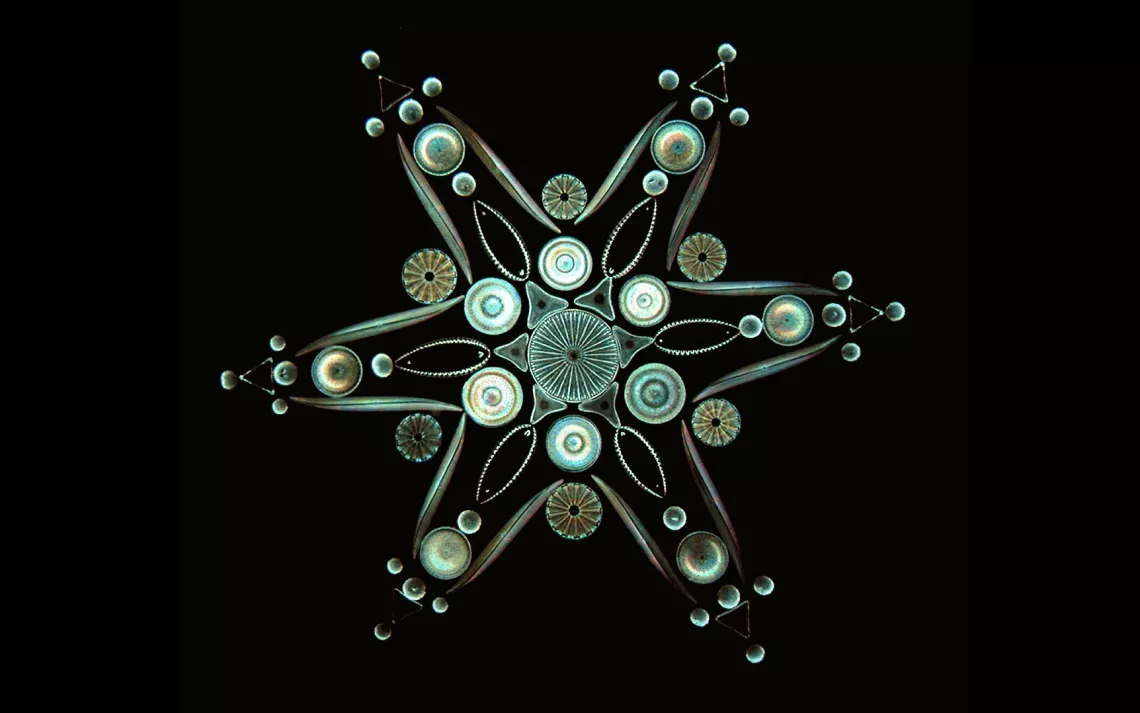

This six-pointed star is made up entirely of diatoms, microscopic algae that build cases for themselves out of glass. These photosynthesizing plankton are ubiquitous—found in oceans, ponds, soils, or really anywhere with water—and extremely tiny, ranging from around 20-200 microns across. Their sheer abundance makes them a major source of atmospheric oxygen, one of the planet’s main carbon fixers, and a vital source of food for aquatic animals.

Howard Lynk, victorianmicroscopeslides.com

Chelsea Leu is a former editorial intern at Sierra.

More articles by this author The Magazine of The Sierra Club

The Magazine of The Sierra Club