The Fine Art of Wildfire Awareness

Inside pyrosketchology—a tool to help Westerners prepare for, and live with, fire

Images courtesy of Miriam Morrill

When Fiona Gillogly was about five years old, she developed a ritual to follow each year as the heat of summer set in: She’d take a large pillowcase and fill it with her favorite stuffed animals. Those chosen toys would remain tucked away for the next few months, easily accessible for Gillogly to grab in case her fears materialized and her family had to evacuate due to encroaching fire. Gillogly was terrified of the wildfires so common in her native California; a whiff of smoke would cause her breath to catch in her chest.

Now almost 18, Gillogly still sees wildfires as a threat to her home, which is perched on the edge of a canyon in Auburn. She still makes a habit of fire preparation, and while she now prioritizes items other than stuffed animals for her “go bag,” the biggest difference between Gillogly’s approach to fire then and now lies in her attitude.

“I sort of lost that fear,” Gillogly says. “I don't have that immediate wincing to the smell of it anymore.”

It’s a shift she tracks back to 2019, when she had the opportunity to experience fire up-close. She and her mother, Beth Kelley Gillogly, were part of a small cohort invited along on a Fire Training Exchange program (TREX) hosted by the Nature Conservancy, the Mid-Klamath Watershed Council, and the Karuk Tribe. As experts presented on the role of fire in California’s ecosystem and the long-standing practice of cultural burns, the Gilloglys filled notebooks with their observations. Beth Kelley’s were in the form of haikus, while Fiona’s were sketches—drawings of drip torches interspersed with notes.

“Noise in the beginning was a little hiss with a few pops,” the younger Gillogly wrote on one page as she observed a cultural burn. “About 30 minutes in, it changed from that to lots of little pops and a few big pops, similar to the sound of crushing very dry leaves.”

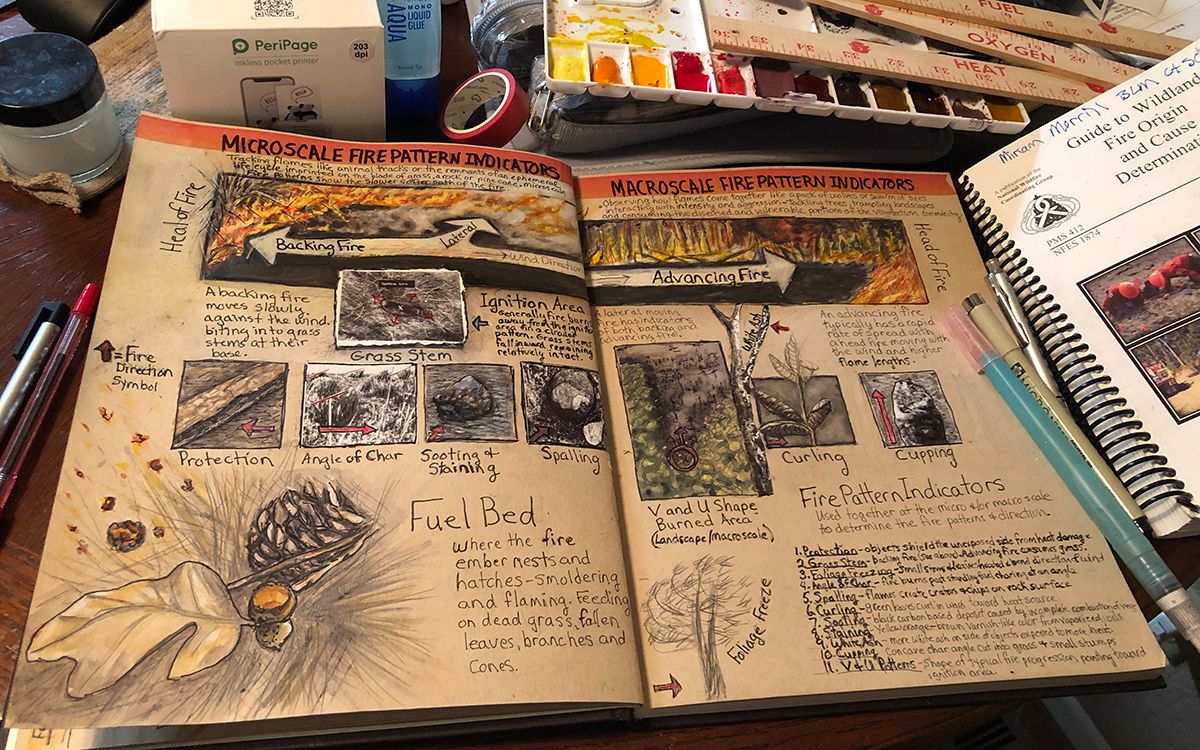

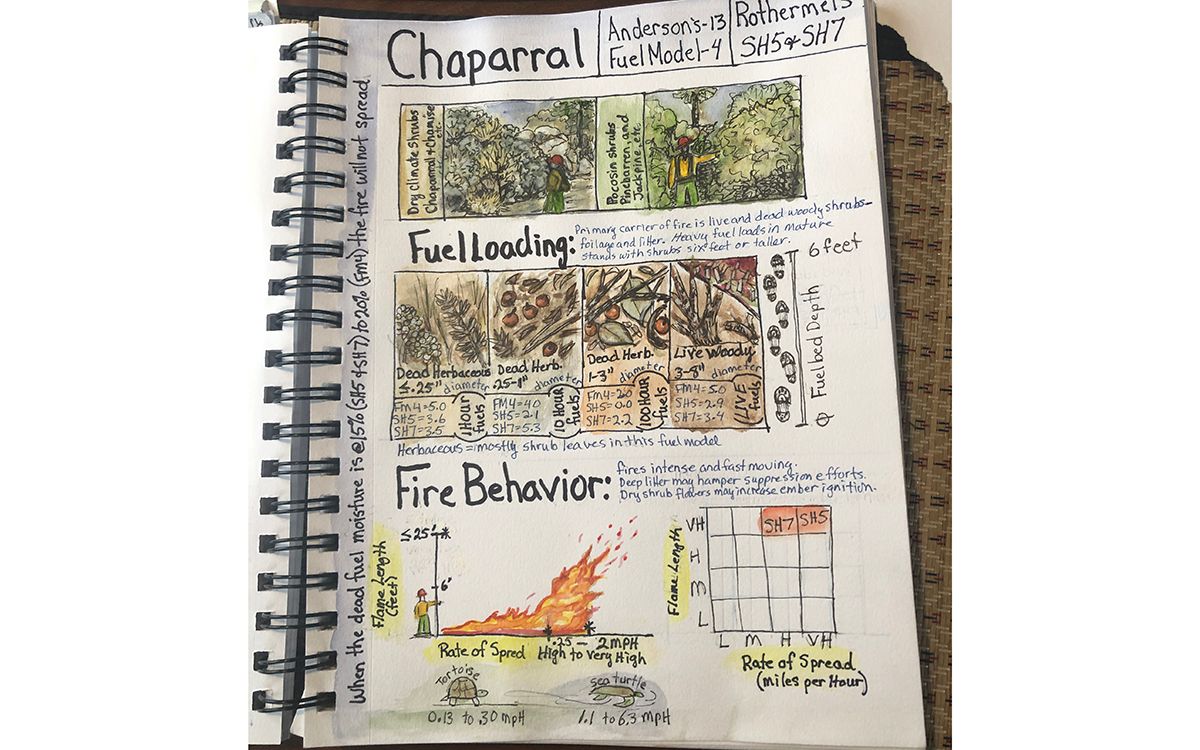

They were participating in a pilot program to teach “pyrosketchology,” a technique developed by Miriam Morrill to marry the study of fire with journaling and illustration. Morrill, then an employee with the Bureau of Land Management, had pitched and designed the workshop to help others develop what she calls “a way of knowing” about fire—the sort of deep situational awareness that causes the hair on the back of her neck to stand when there’s an elevated fire risk. Morrill created pyrosketchology after trying nature journaling and discovering that the observational practice transformed her daily walks, unveiling plants and patterns she never before noticed.

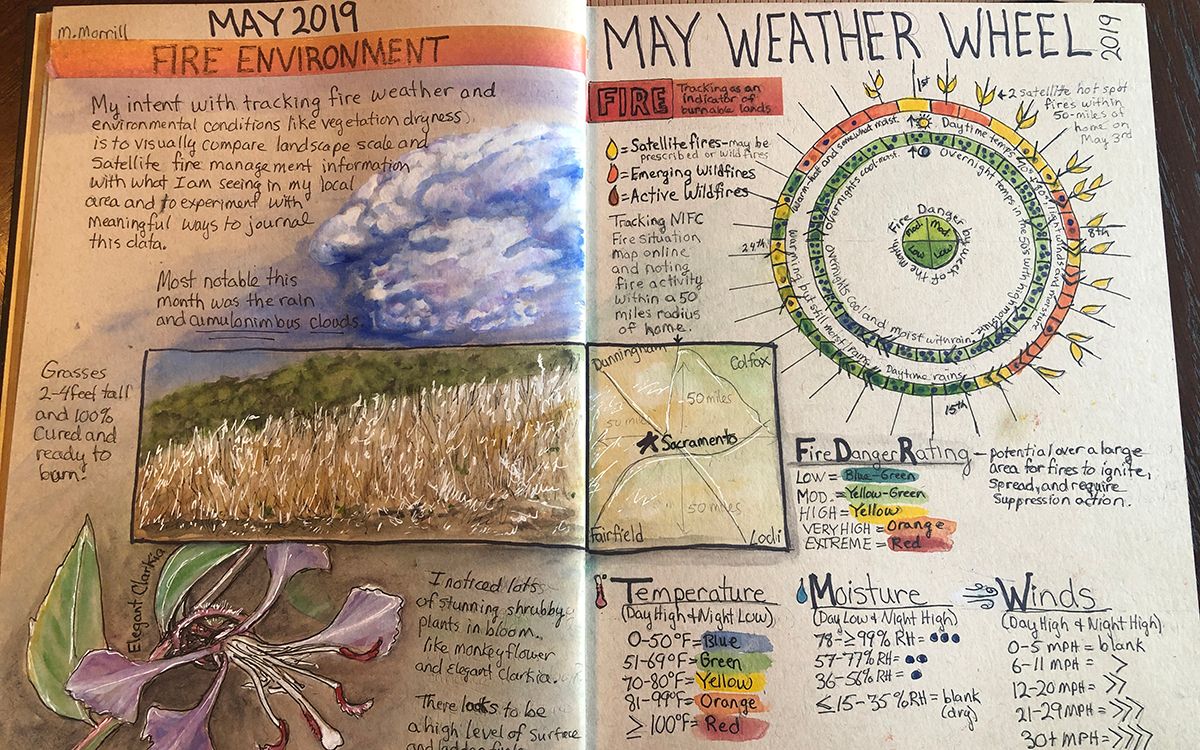

"Weather wheels were a year-long experiment, and each month changed a little as I explored the data and visuals I thought helped me connect and relate to the data," Morrill says. "It was one way to try and overlay my physical sense with data and a visual."

“It really struck me—for somebody working in fire and trying to develop programs or policies focused on communication and education—how I didn't think about this tool,” Morrill says.

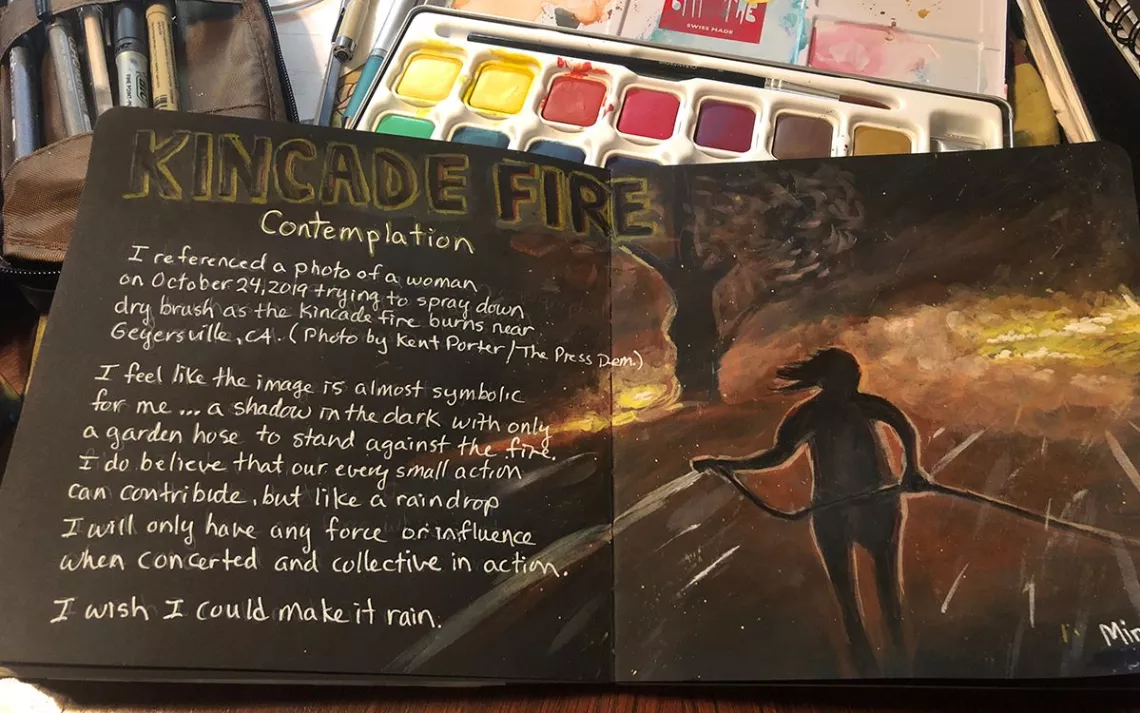

The realization came at a moment when Morrill admits she was feeling frustrated and overwhelmed. She had dedicated more than two decades to fire-related work across federal agencies, and the challenges they presented in the West were seemingly worsening each year. Morrill was particularly impacted by the Camp Fire in 2018, which devastated swaths of Butte County in Northern California, an area she once called home. Following that fire, she worked with CAL Fire and the National Weather Service to lead a year-long social media campaign to raise awareness of what fire weather looks like. But she walked away feeling like it wasn’t enough, given the scope of the problem.

“Not only has fire been excluded from the landscape—and we've seen the impacts of that—it's really been excluded from our sense of place; people haven't been living in these environments with fire happening more normally,” Morrill says. To restore that connection, she believed she needed to help people truly reconnect with nature, including fire, and improve their physical and emotional relationship with it as a part of the landscape. The Klamath TREX gave her an opportunity to put that theory to the test.

For that first workshop, Morrill brought in people with existing interest and experience in natural journaling, including the Gilloglys and Laura Cunningham, an author and illustrator who had previously published an illustrated book chronicling California’s historic and fast-changing landscapes. Cunningham described the experience as “eye-opening.”

“We're raised in school with Smokey the Bear, you know—we've got to always put the fires out; fire is always bad; it's always destructive,” she says. “But [the TREX workshop] kind of showed us these little flickering flames that were inches tall just slowly eating away excess leaf, litter, and twigs. Removing this fuel, reshaping the forest, and restoring it, and it was all very under control and beautiful.”

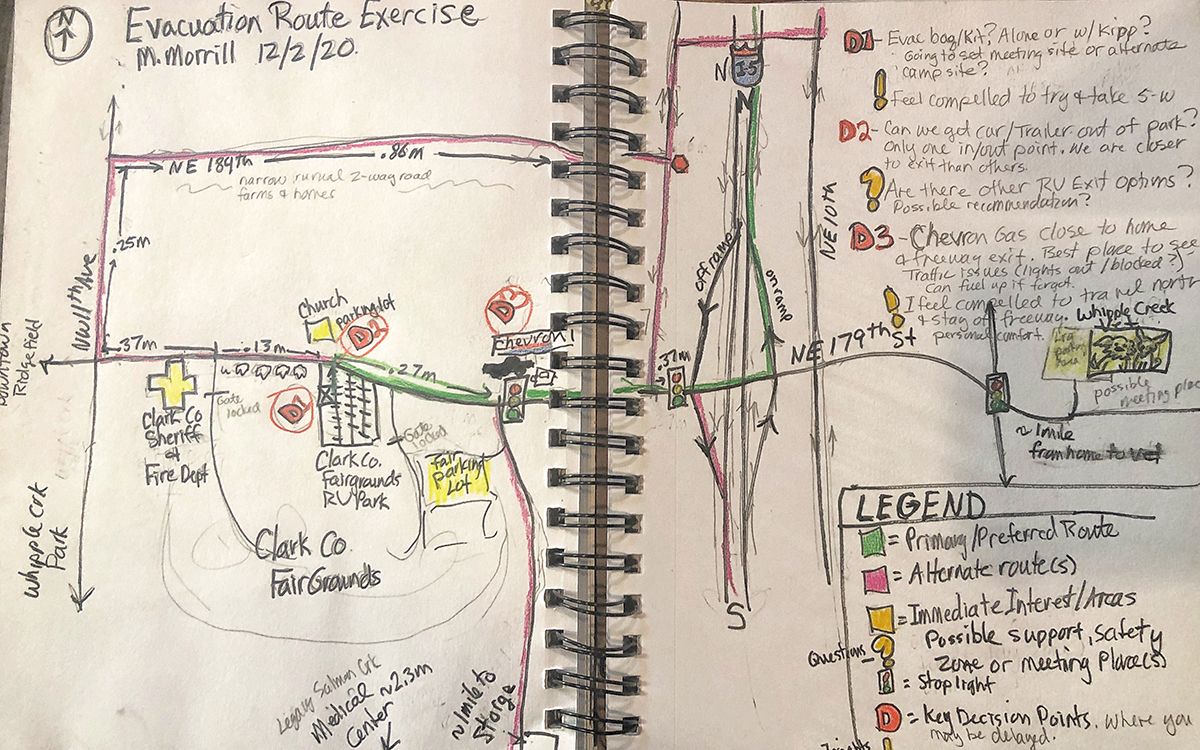

Having seen the TREX workshop “really resonate” with participants, Morrill has since brought pyrosketchology to new audiences (though thanks to the pandemic, most of her subsequent lessons have been virtual). While each course is different, she says there are some fundamentals, like teaching the basics of capturing a scene in a quick sketch and learning how to identify the impacts of fire on the land. Beyond this, she’s been able to center courses around various objectives, such as using fire journaling to enhance evacuation planning or to help firefighters enhance their situational awareness. Mikel Robinson, executive director of the International Association of Wildland Fire (IAWF), recounts watching professionals presenting their journaling following a recent workshop the association offered with Morrill. It was fun, she says, but also gave participants a chance to “open up” a different part of their brains—to maybe even view their work in a new way.

There’s a science behind that, according to Scott Amick, recreation coordinator at the Paradise Recreation and Parks District. Amick has a background in functional neurology and is working with Morrill to develop trauma-informed pyrosketchology programs for fire survivors in Butte County. A Camp Fire survivor himself, Amick admits to being a convert to the practice for its ability to help him down-regulate, or relax, during times of stress by engaging different parts of the brain.

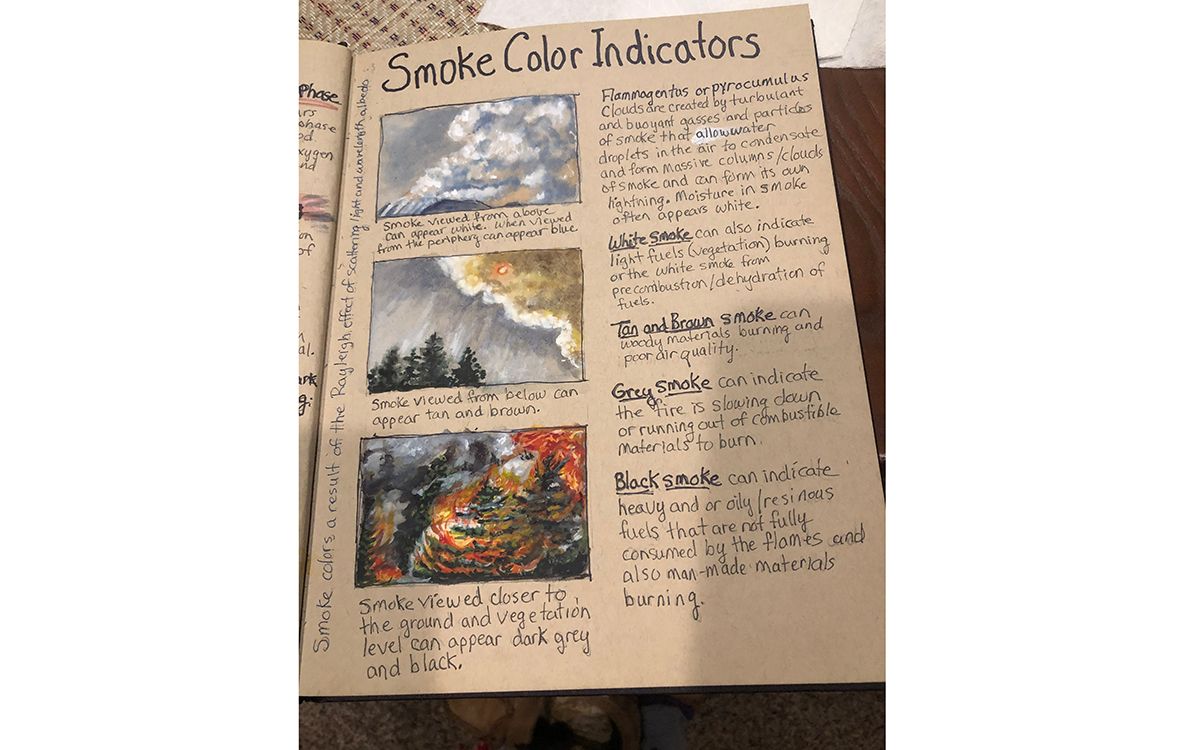

Still, he recognizes that it can all sound a little “woo-woo”—a challenge multiple pyrosketchology converts acknowledge. Marlita Reddy-Hjelmfelt, a technology and communications consultant with clients including the US Forest Service who describes her job as “putting on a hazmat suit and diving into comment threads” during wildfires, sees significant potential in the power of pyrosketchology for the public but notes that she’s received some “glazed” looks when she mentions it. To address that, she attempts to emphasize the observational aspect, rather than the drawing.

“Saying, ‘Hey, these are the things you can look for to know how the fire behavior could change’—it's not so much that you can do anything about changing that, but noticing and being aware of that is kind of empowering,” Reddy-Hjelmfelt explains, adding, “If you have a way to process that, you're much less likely to be spreading misinformation.”

A number of pyrosketchology students have gone on to teach their own courses to help spread the word, including Kathryn Joy Heim, the program coordinator of Fire Adapted Methow Valley in Washington. After having to evacuate from a wildfire in 2014, Heim found herself going into “panic mode” whenever she smelled smoke or heard a siren. Practicing pyrosketchology, she says, has helped her reconnect with her surroundings and thus better understand the real signs of fire danger, a tool she’s now attempting to share with young people in her area through a situational awareness journaling workshop she’s developing.

For Morrill, who has since retired from the BLM, there’s an excitement in this new chapter and in seeing pyrosketchology catch on, even if it is a slow process. And as officials and the public alike continue to adopt new measures in the face of worsening wildfires, she hopes this can simply serve as another tool—one that is affordable and accessible to anyone with paper and a pencil—for people trying to understand how to prepare for and live with fire.

The Magazine of The Sierra Club

The Magazine of The Sierra Club