The Alien Beauty and Creepy Fascination of Insect Art

Through history and across cultures, insects have inspired artists and challenged viewers to shift their perspective

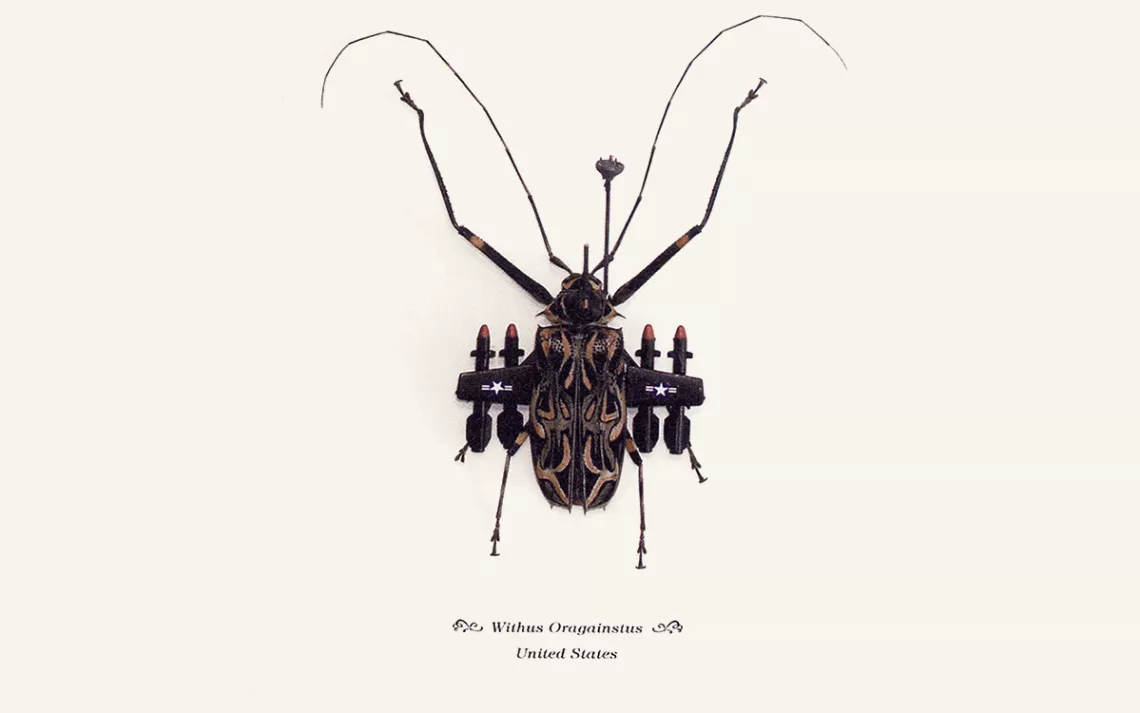

In his antiwar piece captioned “Withus Oragainstus,” the UK-based street artist Banksy militarized a harlequin beetle with airplane wings, missiles, and a satellite dish. The framed specimen was surreptitiously displayed for a short time by the artist in the insect collection at the American Museum of Natural History in New York City. | Photo courtesy of Jan Slangen

This article was originally published in Knowable Magazine, reprinted with permission.

One day when Barrett Klein was a young boy, he found a dead butterfly in the driveway of his family’s house and marveled at its beauty. It was a transformative moment. “At age five I had a nebulous epiphany in which I knew that insects would be the core of my existence,” says Klein, who is now an entomologist at the University of Wisconsin-La Crosse. He’s also an artist, and insects feature prominently in his art.

Throughout history and across many cultures, insects have inspired artists and artisans. Moth larvae, bees and beetles have provided silk, wax, dyes and other art media. Some insects leave traces on their environment that artists capture, while others in effect become collaborators as their natural behaviors are incorporated into art. “With all of their myriad forms, you’ve got exquisite behaviors as well as colors and shapes to choose from, or be mesmerized by,” says Klein, who recently reviewed the role of insects in art in the Annual Review of Entomology.

Much of this work plays on the conflicting feelings we humans tend to have toward insects—we’re simultaneously fascinated by their strange biology and unfamiliar lifestyles and repulsed or frightened by their stingers, toxins and the diseases they may (or may not) carry. Not to mention their sheer scuttling, swarming numbers.

“They don’t live like us. They don’t look like us. They do the things that we do in such bizarre and wild ways that it’s just endlessly intriguing,” says artist Catherine Chalmers. “They offer a very, very different perspective on life on Earth.”

From ancient cricket etchings to beetle shawls

One of the oldest known examples of insect art is an engraving of a cricket carved into a fragment of bison bone found in a cave in southern France and thought to be about 14,000 years old. Ancient people were great observers of the natural world, says Diane Ullman, an entomologist and cofounder of the Art/Science Fusion Program at the University of California, Davis. Insects are found everywhere humans live (they’re scarce near the poles of the Earth and absent only in the ocean’s depths), and they show up in artifacts from Mesoamerica to Mesopotamia. “Insects became part of the cultural and spiritual stories of people all over the world,” Ullman says.

Images of scarab beetles, for example, are common in the religious art of ancient Egypt, where their habit of rolling balls of dung across the ground (to provide food and shelter for their brood) symbolized the god Khepri rolling the sun across the sky each day. In the Navajo creation myth, Ullman says, cicadas lead people to emerge into the world, mirroring their own life cycle of periodic emergence from underground.

The varied use of insect parts and products in art includes (from left to right), lac bug–derived shellac decorating a piece of Tibetan horse armor, iridescent beetle elytra incorporated in an ear ornament made by the Awajún people of South America, and red pigment derived from cochineal insects in a painting by the Flemish artist Anthony van Dyck. | Photo couresty of MetMuseum.org/public domain; B.A. Klein, taken with permission in the collections of the Field Museum of Natual History; A. Van Dyck /public domain

Insects have long provided artists with material for their work. Shellac, derived from the resinous secretions of the female lac bug, has been used for more than 3,000 years. It helps give the sheen to ornate Tibetan armor, among many other examples. Carmine, a brilliant crimson dye derived by crushing up cactus-sucking cochineal bugs and used by the Aztecs and Mayas, commanded exorbitant prices in 16th-century Europe, where it was coveted by artists and textile makers. It made reds pop for Rembrandt and other Dutch master painters.

Some cultures use insects themselves, or at least parts of them. The Zulu people of southern Africa string the tiny bodies of immature scale bugs into elaborate necklaces (the insects coat themselves in protective wax that makes them look a little like pearls). Fireflies add “living jewels” to clothing in India, Sri Lanka and Mexico.

Another striking example is the singing shawls made by the Karen people of Myanmar and northern Thailand, says Jennifer Angus, who teaches textile design at the University of Wisconsin–Madison. These woven garments, so named because they’re worn at funeral ceremonies where mourners sing around the clock for several days, sometimes have a fringe made from the shiny, iridescent elytra, or hard outer wings, of jewel beetles. Angus, who grew up in Canada, had never seen anything like it. “I really had trouble believing that it was real,” she says.

The discovery inspired Angus to start incorporating insects into her own work. Her first installation was at a storefront gallery in Toronto, where she arranged hundreds of weevils into a wallpaper-like pattern on the walls. When people walked up to take a closer look, Angus says, “literally, I saw them take a step back as they realized the wallpaper was composed of insects.” The piece created tension, she says, between what people expect when they see a pattern they associate with domestic spaces and the realization that the pattern is composed of bugs, which most people don’t like to find in their homes.

Angus continues to exploit that tension in her work. “A lot of people don’t like insects, but they’re OK with them when they’re put in patterns, because a pattern is ordering and it’s asserting a kind of control,” she says. “When I put them into something that’s sort of like a swarm, people find that very disturbing because that’s mimicking what they actually do in the wild.”

Making art from insect creations

Experimental designer Marlène Huissoud says she’s had a similar reaction to some of the objects she creates from products made by bees and other insects. “A lot of people, when they see the pieces, they say they are very attractive … but at the same time there’s something a bit scary to them,” she says.

Huissoud grew up around bees—her father was a beekeeper in the French Alps—and her work applies methods that are commonly used with industrial materials to products made by insects. In some projects, for example, she’s used glassblowing methods to work with bee propolis, a resinous substance that bees use to build and repair their hives. (To make it, bees gather plant resin from leaf buds and bark and process it with saliva and secretions from their wax glands.) Huissoud says she can harvest 50 kilograms of propolis a year from her father’s 700 hives—a small haul compared to the roughly 20,000 kilograms of honey they extract.

Huissoud devised a low-temperature kiln to work with propolis, which melts at around 100° Celsius (212° Fahrenheit), compared with 1,200°C or so (about 2,200°F) for glass. But from there the process is similar: building up layers of melted resin on a rotating rod and allowing it to cool slightly before blowing it. In her Of Insects and Men series, she used both bee propolis and actual glass to “disturb the eye of the audience” and challenge notions about what’s a natural material and what’s an industrial material. The bee propolis binds the shards of black glass together. “It’s only when you see them in real [life] that you actually realize it’s pure resin because it’s really smelling like in the beehive.”

Other artists work with the traces that insects leave behind. Seattle-based artist Suze Woolf first noticed evidence of bark beetles while hiking in the forests of the Cascade mountains near her home. Bark beetles are small insects that lay their eggs under the bark of trees. In the process, they excavate tiny tracks through the phloem, the vessel-laden tissue that distributes sugar and nutrients made by the leaves to other parts of a tree. These squiggles caught Woolf’s eye when she saw them on bits of bark that had fallen to the ground. “They look very much like a strange script that we just can’t read,” she says.

The resemblance to written language inspired Woolf to create a series of 36 (and counting) unconventional books that incorporate bark beetle tracks in different ways. One, called Survivorship, was inspired by the chemical warfare that takes place between mountain pine beetles and the trees they choose as hosts. The trees release aromatic compounds called terpenes to deter the beetles, but the beetles are able to convert some terpenes into a pheromone that attracts more beetles and can initiate a mass attack. The cover of Survivorship is an actual slice of log engraved with mountain pine beetle tracks; the pages contain ink reproductions of beetle tracks overlaid on the genetic code for monoterpene synthase, one of the enzymes that trees use to generate defensive chemicals.

Woolf says Survivorship was inspired in part by research by University of Montana entomologist and ecologist Diana Six, who has been searching for genetic variations and differences in trees’ chemical defenses that might explain why some trees survive beetle outbreaks and others don’t. Other books in Woolf’s series incorporate other bits of scientific data—graphs showing the spread of bark beetles through forests in British Columbia and Alberta, for example, or satellite images that show the resulting damage to trees—gleaned from conversations with scientists and from reading their research. “They teach me things I didn’t know,” Woolf says of her scientific collaborators. “I get ideas I wouldn’t otherwise get.”

Science, not art, was what initially motivated Walter Tschinkel to make casts of underground ant nests, something he’s been doing for decades. “I thought I knew what they looked like underground just from having dug them up,” says Tschinkel, a myrmecologist (an entomologist specializing in ants) and emeritus professor at Florida State University. “It turned out I hadn’t really imagined it correctly.”

As he recounts in his 2021 book, Ant Architecture: The Wonder, Beauty, and Science of Underground Nests, Tschinkel tried several materials, including latex and dental plaster, before finally settling on molten aluminum. The tricky part, naturally, is heating aluminum beyond its 660°C (1,220°F) melting point in the field and pouring it into an ant nest without hurting yourself. To do this, Tschinkel developed a portable kiln fired by charcoal. He used the bottom half of a steel scuba tank as a crucible. Sometimes he uses zinc, which has a lower melting point than aluminum and stays liquid longer, penetrating further into finely structured nests. Once the metal cools, it can take hours to dig out the cast of a large nest and clean it up. (A video of Tschinkel’s process has been viewed more than 370,000 times on YouTube.)

Myrmecologist Walter Tschinkel stands next to a plaster cast he made of a Florida harvester ant nest. The 8.5-foot-long sculpture captures the intricate structure and depth of the underground nest. | Photo by Charles F. Badland/Wikimedia Commons

The molten metal captures the intricate chambers and passages of the nest, which turn out to be a lot less random and more organized than Tschinkel had realized. Tschinkel describes it as a “shish kebab” structure, with many horizontal chambers connected by long vertical tunnels. “Practically all nests have that basic structure, which tells me that the ancestral ant a hundred million years ago probably dug a simple nest … and from that basis all other nests have evolved.”

Harvester ant colonies can live for 30 or 40 years and, when possible, Tschinkel waits for a colony to move to a new nest before making a cast, to avoid killing the inhabitants. “I’m very fond of them,” he says. He estimates he’s made several hundred casts over the years, including the nests of about 40 species, most of them native to Florida. “I think they’re beautiful objects,” he says. “That’s part of the joy of doing this kind of work.”

Artist-insect collaborations

Insects may be unwitting collaborators in the work of Woolf and Tschinkel, but some artists see them as collaborators in a more literal sense. One colorful illustration of this is the French artist Hubert Duprat’s work with caddisflies, a group of insects related to butterflies and moths. Caddisfly larvae feed on decaying leaves and other detritus in rivers and streams. They encase themselves in a protective layer of silk, which they adorn and reinforce with grains of sand, pieces of twigs and other materials in their environment.

Duprat wondered what the larvae could do with more glamorous materials. So he raised some in an aquarium, giving them access only to flecks of gold, tiny pearls and bits of precious stones. The insects fashioned new, blinged-out cases for themselves. “The work is a collaborative effort between me and the caddis larvae,” Duprat says in a video segment on the project. “I create the conditions necessary for the caddis to display their talents.” Last year, Duprat published a book on his caddisfly collaboration, The Caddisfly’s Mirror.

Insect behavior itself becomes the art in the work of Catherine Chalmers. In one long-running project, she photographed and filmed leafcutter ants in Costa Rica. These ants cut bits of leaves from high in the forest canopy and carry them back to their underground nests to provide a substrate for the fungi they cultivate as food. They use airborne chemical signals and vibrations to coordinate their activities, and their colonies can sustain millions of individuals. The eminent biologist E.O. Wilson called leafcutters “the most complex social creatures other than humans.”

In a series of works Chalmers describes on her website as intended to “blur the boundaries between culture and nature,” she carted 300 pounds of camera gear to Costa Rica each winter to create works based on the ants’ natural behavior in ways that draw parallels to our own. In one series, called War, she captured gruesome scenes from a three-week battle between two colonies in which many ants were dismembered and killed. Chalmers placed white plastic sheets around the area where the ants were fighting before filming them (the ants quickly habituated to the sheets and resumed their nightly battle). A video from the series looks like it was staged and filmed in a studio, even though Chalmers filmed it in the field. This somehow makes it more disturbing to watch than if it looked more like a nature documentary.

Chalmers doesn’t kill the insects in her work, although sometimes that’s how it looks. In a series called Executions, she placed cockroaches purchased from a biological supply company and kept in her New York City apartment in scenes of a hanging, an electrocution, a gas chamber and so on. In one, she filmed a live cockroach tied to a stake (she blew on it to make it move), then swapped in a cockroach that had died of natural causes before setting the stake on fire. The series elicited varied reactions, Chalmers says, from someone in San Francisco who ran out of the theater, to a man at her show in Boise urging her to kill as many cockroaches as possible.

“In her executions series, she really stirred emotions—you could argue in surprising ways—from people who might not think twice about spewing pesticide or squashing cockroaches,” says Klein. The series raises an interesting question, he says: Does seeing a cockroach play the part of a human condemned to die change how you feel about the cockroach? “Do you extend your circle of empathy … to a hexapod?”

Other artists have gone further, implanting computer chips in living insects or staging live fights, as in Chinese artist Huang Yong Ping’s controversial work Theater of the World. For Klein, the latter, at least, is a step too far. “I think that’s a gratuitous display of gladiator-style entertainment,” he says. “You’re purposely throwing organisms together to cause harm to each other, and I don’t see much value in that, but others might and others have. I think all of us draw our own lines.”

Many artists hope their work with insects will raise awareness of the important roles the creatures play in the environment and provide a lens through which to reexamine our own influences on the natural world.

“The longer I’ve worked with insects, the more I’ve learned about them,” says Angus. “I’ve come to an understanding of just how important insects are to, frankly, our wellbeing on this planet.” Insects pollinate plants, including many food crops, and they play integral roles in diverse ecosystems as decomposers of waste and as parts of the food chain. Some of them may be sentinel species for the impacts of climate change—the mountain pine beetles Woolf has worked with, for example, are expanding their range northward and taking a bigger toll on trees made more susceptible to attack by the stress of longer, hotter springs, summers and falls.

There is still tremendous untapped potential for artists interested in working with insects, says Klein. He examined 164 works of insect art for his recent review article and found that the majority involved just two orders of insects, Hymenoptera (which includes bees) and Lepidoptera (butterflies and moths). Even within those two orders, the two species with the most extensive history of human exploitation—honeybees and silkworms—were heavily overrepresented. “What about the other 183,000 described species of Lepidoptera?” Klein asks. In addition to new silks and dyes, there may be other materials artists could use—like chitin, the tough, lightweight material that forms much of the exoskeleton of insects. Engineers have considered chitin for building structures on Mars, he says, but the artistic possibilities have scarcely been explored.

With many millions of insect species (only about a million of which have been named) and 10 quintillion individuals, the world is literally crawling and buzzing with possibilities.

The Magazine of The Sierra Club

The Magazine of The Sierra Club