By Sean Cummings

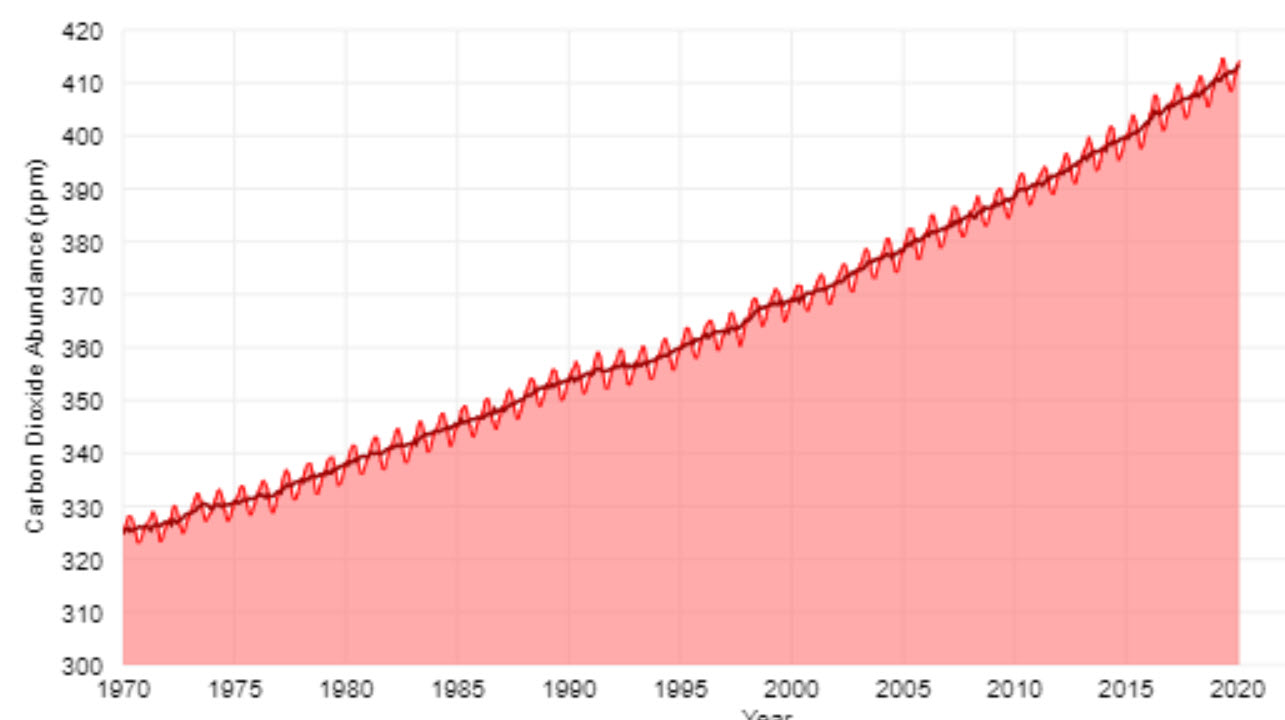

The year of 2020 may see an eight percent drop in global greenhouse gas emissions, according to the International Energy Agency.

That may look small, but it would be the greatest ever recorded. It would mean 2.6 billion fewer tons of carbon dioxide emitted than last year, returning humanity to 2010’s emission levels. And it’s happening for a reason none would wish for.

The Covid-19 pandemic has forced the world into lockdown; many nations have seen energy use drop up to 25% from 2019 levels.

The implications for climate change remain uncertain. Low energy demand has given market priority to renewables like solar and wind which are cheap and easy to keep running. Meanwhile, many experts predict the coal industry will not recover from the pandemic’s impacts.

Historically however, emissions tend to rebound as governments revive their economies after a crash. Whether this happens in the wake of Covid-19 depends on whether renewable energy investments are part of economic revival efforts.

This choice matters now more than ever, as the latest climate science reminds us of what may lie ahead otherwise. For instance, under business-as-usual, a third of humanity may live in areas with annual mean temperatures exceeding those humans have historically tolerated. And many of these regions—mostly in the global south—have already experienced a doubling since 1979 of weather events combining extreme heat and humidity, a deadly mix that undermines the body’s ability to cool through sweating.

Humans don’t face these impacts alone. In April, a study in Nature revealed that many species’ populations, rather than dwindling gradually, will abruptly collapse once their habitats pass certain temperature thresholds. The study projects 73% of species passing such thresholds before 2100 will do so within a few years of each other, causing rapid breakdowns of entire ecosystems. Oceans, absorbing the bulk of global warming, may experience such catastrophes this decade.

As coastal SoCal is warming twice as fast as the continental U.S. the Los Padres region sits on the frontlines of climate change. Ocean warming has depleted kelp forests around the Channel Islands, reducing our region’s ability to sequester carbon (global kelp forests sequester 600 million tons of carbon dioxide annually). The morning marine layer has declined up to 50% in parts of Santa Barbara and Ventura counties since 1970, increasing fire risk. And Ventura County remains the fastest-warming county in the lower forty-eight at a 2.6 degrees Celsius increase since 1895.

If these trends continue, by 2050, our region can expect four to six degrees Fahrenheit of warming (including a doubling of extremely hot days from present) and five to seven fewer inches of annual rainfall. We can also expect fewer “chill hours,” the nighttime temperature drops many crops need for proper fruiting. Heightened wildfire conditions will likely continue; California’s 2020 wildfire count has already jumped 60% from this time last year.

Experts aren’t sure why our region suffers outsized impacts. But many point to transportation emissions. Urbanization in Los Angeles and Orange counties, combined with a housing shortage and heavy tourism in Santa Barbara and Ventura counties, have kept traffic surging, leading some environmentalists to advocate for replacing parking lots with high-density housing.

As the Covid-19 pandemic has locked down labs and strapped research for funding, we thank the scientific community for carrying on as best it can. Climate scientists’ insights may hold a key to designing a pandemic recovery that will leave us hopeful for the future of the Earth’s climate.

Carbon Dioxide concentration in the atmosphere continues to rise despite current drop in emissions. Source NOAA.