Two years ago, hiking in an old-growth forest in the Hudson River Valley, I was unaware that I had been bitten by a blacklegged deer tick. Following a typical fourteen-day incubation period for symptoms to appear, I was admitted to UW Hospital, through the emergency department, with a headache, 102° fever, chills, nausea, vomiting, respiratory stress, swollen and painful joints, and tachycardia. It took four days before a blood test confirmed a diagnosis of anaplasmosis, one of sixteen known infectious illnesses like Lyme disease that are carried by this minute, pesky parasitic arachnid.

We, as humans, are ecologically intertwined with every living thing in our environment. It’s as simple as the exchange of oxygen we inhale and carbon dioxide we exhale. The quality of air we breathe, water we drink, and food we eat affects our global, community, and individual health either positively or negatively. And the quality of these essential life-giving ingredients depends upon how individuals, businesses, and governments manage vital natural resources.

In fact, the World Health Organization reports that 24 percent of all diseases, illnesses and adverse conditions in the world are environmentally-caused. The evidence surrounds us daily. Consider increasingly frequent outbreaks of E. coli and salmonella in our food supply. Global warming has contributed to this trend of adverse health conditions, challenging our public health and clinical delivery systems in terms of prevention and treatment. Additionally, increased tick-borne diseases threaten public health; some of these diseases can be fatal. Certainly, costs to individuals and public resources have increased, and will continue to be an economic consequence of the assault on our environment.

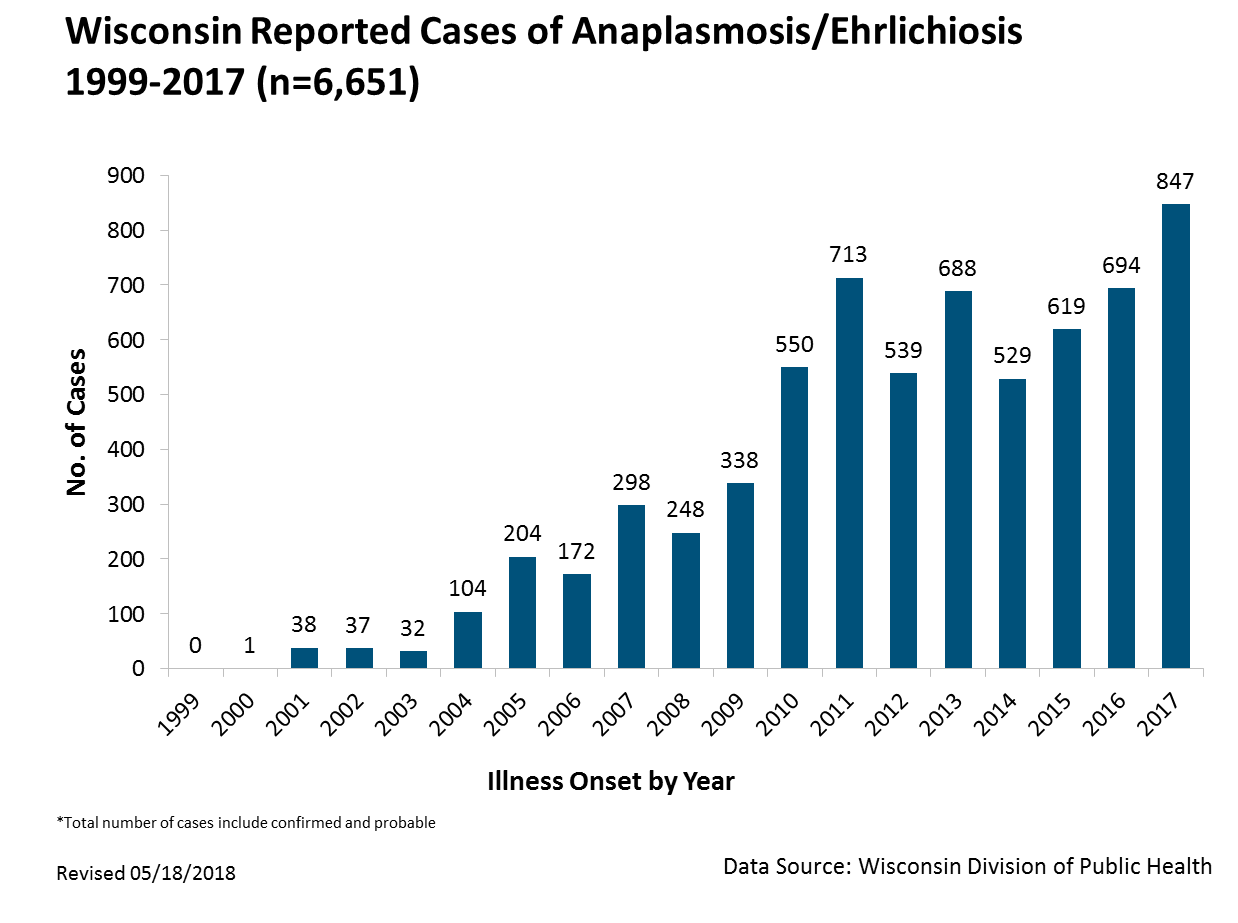

An excellent example is the growing incidence of mosquito, flea and tick-borne diseases. In particular, there has been a rapid rise in the number of nationally reported anaplasmosis cases, a tick-borne disease that causes fever, headache, chills, and muscle aches. The CDC reports an 800 percent increase from 2000 to 2016, and is likely that some cases go under-reported for a variety of reasons, such as misdiagnosis or individuals not seeking medical care. The incidence of reported anaplasmosis cases is highest in the northeast and upper Midwest. Ninety percent of reported cases come from eight states, one of which is Wisconsin.

A report by the American Public Health Association and CDC says that climate change poses many risks to human health. Warmer weather means longer periods for ticks and other insects to thrive and increase the incidents of vector born disease (an organism that transmits a pathogen from one host to another, such as from deer to human). Milder winters now mean that ticks survive longer. A friend working to clear brush on the Ice Age Trail near Janesville told me he picked a tick off of his jacket on a snowy, bitter cold December day; even when there are very cold days, the overall warmer winters mean that ticks are surviving through the season.

At an individual level, since my adverse tick experience, in addition to mosquito repellant, my wife and I douse our exposed skin, light-colored clothes and hiking boots with benign chemicals (DEET, permethrin, picaridin). We avoid hiking in tall grass and tuck our pants into our boots. We assiduously check our exposed skin for ticks and shower after hiking. We frequently hike with our grandchildren and meticulously (to their chagrin) examine them. We also make sure that our beloved English cocker spaniel is protected with preventive tick medicine and inspection after running in the park.

What can be done? At a global and national level, we must advocate for aggressive policies to protect the natural environment as supported by the Sierra Club and other advocacy groups. The public should be made aware of the connection between environmental degradation and negative impacts on our health.

By Martin A. Preizler.

Photo of blacklegged deer tick courtesy of Lennart Tange. Graph from Wisconsin Department of Health Services.