Will Mexico’s New Climate Scientist President Change the Country’s Energy Policy?

Claudia Sheinbaum made history. Whether she will modernize Mexico’s climate policy is unclear.

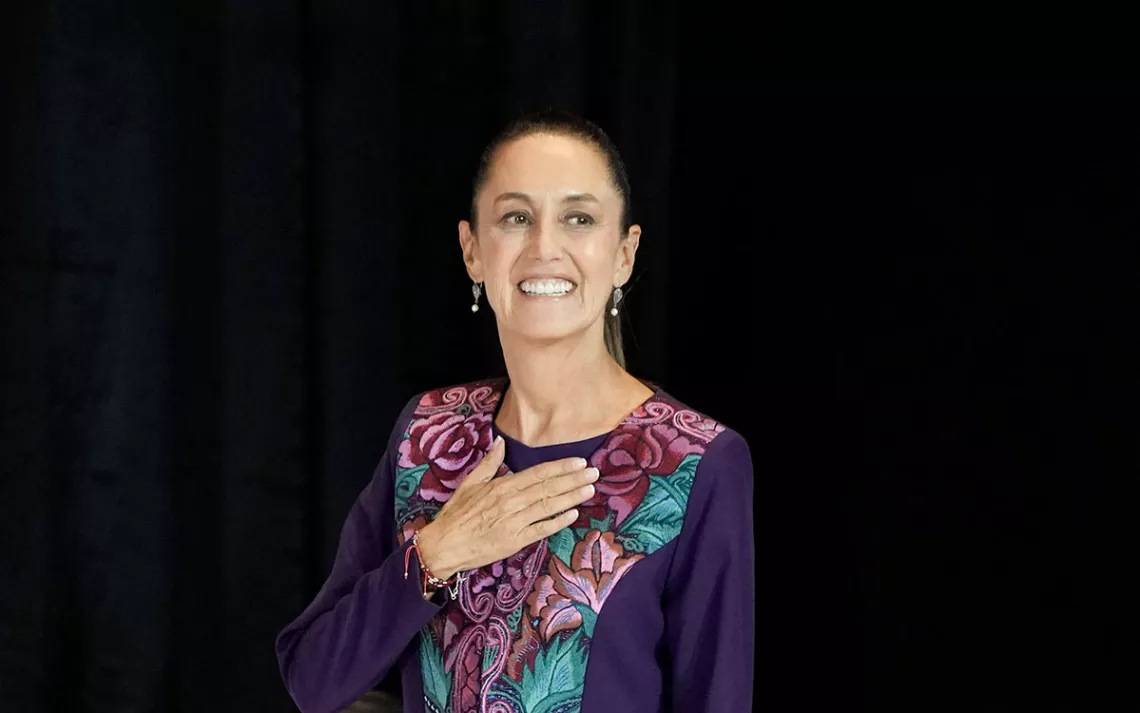

Ruling party presidential candidate Claudia Sheinbaum greets supporters after the National Electoral Institute announced she held an irreversible lead in the election in Mexico City. | Photo by Eduardo Verdugo/AP

On Sunday, June 2, Mexican voters made history: They elected the nation’s first female president and its first Jewish president. Claudia Sheinbaum, a 61-year-old energy and climate scientist from the ruling Morena Party, beat out the main opposition candidate by more than 30 points. Her party also took the House and came within two seats of winning a super majority in the Senate.

Sheinbaum’s election also marks the first time that a member of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) will lead a nation.

Sheinbaum's and Morena’s resounding victories give Sheinbaum both a popular and an institutional backing unprecedented since the crumbling of the once-hegemonic Party of the Institutional Revolution (PRI) nearly 30 years ago. Sheinbaum could try to make her mark precisely in her area of expertise: renewable energy and climate change. She could pursue concerted government actions to cut fossil fuel dependency, support clean forms of energy, and protect Mexico’s biodiversity. Her actions as mayor of Mexico City and her statements supporting outgoing president Andrés Manuel López Obrador’s policies, however, cast her commitments in doubt.

The anxiety of influence

Sheinbaum’s campaign was often discussed as a referendum on López Obrador’s six-year term, and the candidate herself was assumed to be a kind of placeholder for López Obrador. Sheinbaum remarked on the sexism of this later assumption, even as she seemed to fully embrace the former. Throughout her political career, she has remained fiercely close and loyal to López Obrador, and she has explicitly committed to continuing his project of “national transformation” once in office.

López Obrador’s legacy is not as straightforward as his popularity might indicate. While he raised the minimum wage, reduced poverty, and created old-age pensions, he also spent billions on oil development and highly controversial construction projects. He further militarized the country, ignored the outrageous violence linked to the drug trade, and sabotaged the commitments he made to investigate prior state crimes, principally the mass forced disappearance of 43 rural college students in 2014. Mexico’s 2024 elections were historic in another, more awful way: They were among the most violent in recent history. Some 36 candidates and 14 relatives of candidates were murdered in the lead up to election day.

Sheinbaum is unlikely to deviate from her mentor’s social assistance programs, militarization of public security, and denial of Mexico’s human rights crisis. But will she chart her own path when it comes to the environment?

“Considering what Sheinbaum knows about the climate crisis, I’d like to believe that she will put her knowledge into practice and lead us toward the progressive elimination of fossil fuels,” said Claudia Campero, a geographer who collaborates with the climate action group Conexiones Climáticas. “This has not been a part of her campaign, however, which has followed the president’s discourse that Pemex [Mexico’s state-owned oil company] equals national sovereignty.”

Lazaro Cárdenas, the ideological father of the once dominant PRI, nationalized Mexico’s oil in 1938, expropriating the assets of most foreign oil companies and creating Pemex. Cárdenas is one of López Obrador’s heroes, and oil has been intertwined with sovereignty, anti-imperialism, and Mexican nationalism ever since. In 2023, on the 85th anniversary of the nationalization of the oil industry, López Obrador claimed his government’s support of Pemex would guarantee absolute “oil sovereignty.” In pursuit of such “oil sovereignty,” López Obrador’s government built a new $16 billion oil refinery called Dos Bocas and made plans to further expand oil and gas development.

“Unfortunately, Sheinbaum celebrated Dos Bocas,” Campero said, “and maintains the idea that gas is needed to generate electricity and has said she will continue in this direction.”

Student, activist, scientist, mayor, president

Claudia Sheinbaum was born in Mexico City in 1962, the daughter of two scientists and granddaughter of Jewish immigrants from Europe. She grew up in a middle class, left-leaning household and studied music and dance. She was active in left-wing political organizations all while pursuing multiple degrees. She earned an undergraduate degree in physics, a masters in engineering, and a PhD in energy engineering, all from the highly respected National Autonomous University of Mexico.

Sheinbaum joined the Democratic Revolutionary Party (PRD), founded by Cuauhtémoc Cárdenas after the electoral fraud of 1988. (López Obrador was also a founding member of the PRD.) A photograph from 1991 shows a young Sheinbaum at Stanford, in a protest against president Carlos Salinas de Gortari, holding up a sign that reads “Fair Trade and Democracy Now!!”

In 2000, after being elected mayor of Mexico City, López Obrador invited Sheinbaum to be his environment minister. She accepted. Her tenure was somewhat marred by a scandal involving her husband at the time, Carlos Ímaz. In 2004, Ímaz was caught on video accepting a suitcase full of cash, part of an attempt to derail López Obrador’s upcoming presidential bid known in Mexico as the videoescándalos. The scandal ended Ímaz’s political career, but not López Obrador’s campaign. (Sheinbaum and Ímaz divorced in 2016.)

When López Obrador lost the presidential election in 2006 (he claimed the election was stolen) by less than half a percentage point, Sheinbaum returned to academia, publishing widely on alternative energy and working, unpaid, on the IPCC reports in 2007 and 2014. In 2012, López Obrador announced she would be his environment minister if he were to win the presidential election that year. He didn’t. In 2015, Sheinbaum became the supervisor of one of Mexico City’s districts and then ran for mayor in 2018, parallel to López Obrador’s presidential election. Sheinbaum was the first woman to be elected mayor of Mexico City.

Sheinbaum’s time as mayor was marked by the Covid pandemic, the tragic collapse of a new segment of the Mexico City subway—killing 27 people and wounding 80—and a women’s uprising against feminicide and impunity. Her legacy with all three is mixed. While she wore a mask and called for a science-based response to the pandemic (in contrast to López Obrador), Mexico City’s health-care system collapsed, leading to a disproportionate number of Covid-19 related deaths. The Mexico City government also used discredited science to support treating Covid patients with ivermectin.

She appointed a highly respected female special prosecutor for feminicide but also sent riot police to repress feminist protests. When asked explicitly about abortion during the first presidential debate, Sheinbaum avoided pronouncing the word itself, responding that “the National Supreme Court of Justice already decided that, what we need to talk about are women’s rights in broader terms.” (That is not exactly true. The court decided that the criminalization of abortion is unconstitutional, but abortion still remains criminalized in the federal penal code as well as in 20 states.)

During her tenure as mayor, Sheinbaum increased green spaces and solar energy in the city, while further electrifying and expanding the routes of electric bus services. She promoted city rainwater harvesting programs to provide potable water in marginalized areas.

But her government also built an overpass that devastated a beloved stretch of wetlands inside the protected natural area of Xochimilco. And Sheinbaum supported López Obrador’s federal policies that often pulled in the opposite direction of the city’s climate priorities.

One of López Obrador’s cornerstone environmental policies is called Sembrando Vida, or Planting Life. The program offers state subsidies to small landowners to plant fruit trees in deforested regions. Over the past several years, however, many people in rural areas deforested their lands to obtain the subsidy. Many then planted monocrops after cutting down biodiverse native species. Critics claim the program has also been used to divide Indigenous communities, break up their territories and foment social conflict.

And there has been a lot of conflict in recent years. According to a report by the Mexican Center for Environmental Rights, more than 75 environmental activists and defenders were murdered during López Obrador’s six-year presidential term. Sheinbaum has not addressed such violence, particularly as it effects Indigenous communities.

During a campaign rally in Chiapas last April, Sheinbaum promised more social assistance programs, said that Indigenous women’s work would be respected and that her government would respect Indigenous autonomy, going so far as to say that it, “will be established in the constitution.”

“It remains to be seen what relationship Sheinbaum will establish with Indigenous peoples, who are the main guardians of biodiversity,” said Adazahira Chávez, the Mexico-based communications coordinator for Indigenous Peoples Rights International. “So far, the vision of López Obrador’s political movement has been paternalistic and has not advanced in an effective recognition of Indigenous rights to self-determination. But if Sheinbaum wants to underpin the foundations for a sustainable Mexico, this would necessarily involve granting full recognition of the territorial rights of Indigenous peoples, including their systems of governance.”

As is the case with any politician swept into the presidency without having held high-level national office, it is difficult to measure the distance between Sheinbaum’s campaign rhetoric and her actual plans. She is known to be a disciplined, hard-working, science-driven, and fact-based politician. But her support for López Obrador’s environmental legacy with Pemex, Planting Life, and the Maya Train—an environmentally devasting tourism cash cow, opposed and denounced by Mayan Indigenous peoples—shows that she is still, after all, a politician.

The Magazine of The Sierra Club

The Magazine of The Sierra Club