At COP16, South American Nations Face the Climate Crisis in Real Time

Signs of climate chaos plague this week’s Peace With Nature biodiversity conference

For South American countries attending this week’s COP16 conference on biodiversity in Cali, Colombia, climate change isn’t theoretical. The fallout is happening right now.

A months-long drought in Bogotá, formerly infamous for its rainfall, has forced city officials to resort to water rationing. Similar droughts in Ecuador, which heavily relies on hydropower for electricity, have caused power shortages in the Andean country as well as exacerbated forest fires that have damaged electrical infrastructure. Government officials have responded with planned rolling blackouts to reduce stress on the national power grid. Forest fires are sweeping Bolivia, as well as Brazil, where just months before, historic flooding displaced nearly 600,000 people.

The multiple crises made for a potent backdrop as Latin American leaders from across the region, and diplomatic personnel from around the world, arrived in Cali to attend the United Nations COP16 conference, which kicked off on Monday. The summit is organized around the theme “Peace With Nature”—though in speeches and casual conversation throughout this week’s events, most acknowledged that there were few signs of peace to be had.

Gustavo Petro, Colombia’s first leftist president in more than 50 years, opened the event with a speech to world leaders that repeated calls for debt forgiveness from wealthy nations in return for climate action in South America. He also endorsed a “global and humanitarian revolution in favor of life,” calling on nations to rethink market-based ideas that favor economic development over the environment, which he described as “the politics and ideology of death.” Shortly after taking office, Petro ended new oil and gas exploration contracts in the country and has made reducing deforestation one of the key goals of his administration. Amazon rainforests represent nearly 40 percent of his country.

Brazilian president Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva, better known as Lula, is also attending the conference. He and Petro lead the most biodiverse nations in the world and govern huge sections of Amazonian regions. But despite their kinship on many political and geopolitical issues, they sharply disagree on a number of environmental issues, from Amazon custodianship to investments in fossil fuels. Lula campaigned on reducing deforestation as well. But he has also auctioned off oil contracts in Amazonian regions as well as proposed building roads into rainforest regions to encourage agricultural developments.

In both Colombia and Brazil, a lack of state presence in Amazonian regions has hampered the ability of government officials to address criminal actors who are engaged in illicit activities such as illegal logging, mining, coca cultivation, land grabs, and unlicensed cattle ranching.

In Colombia particularly, conflict is an obstacle to state conservation efforts. A new report from the International Crisis Group (ICC) suggests that historic reductions in deforestation in Colombia may have been more due to criminal armed groups than government programs. Petro entered office with ambitious plans to negotiate directly with armed non-state actors, a plan he called Total Peace. Two years later, he has little to show for those efforts, and groups that formerly had a motive to display their control over rainforest regions through reduced deforestation are no longer at the negotiating table.

As a result, deforestation is on the rise again. The ICC expects levels this year to rise to the highest point since 2021, a year before Petro took office. An uptick in cattle ranching, both legal and illicit, this year threatens to undo much of his progress on reduced deforestation rates. Meanwhile, a new report from the World Wildlife Federation (WWF) warns that the world is fast approaching a dangerous and irreversible tipping point driven by the combination of nature loss and climate change. The average size of monitored wildlife populations have suffered a catastrophic decline of 73 percent in just 50 years (1970–2020). As a result, ecosystems across the world are more vulnerable to climate change, leading to regional tipping points with global implications for biodiversity.

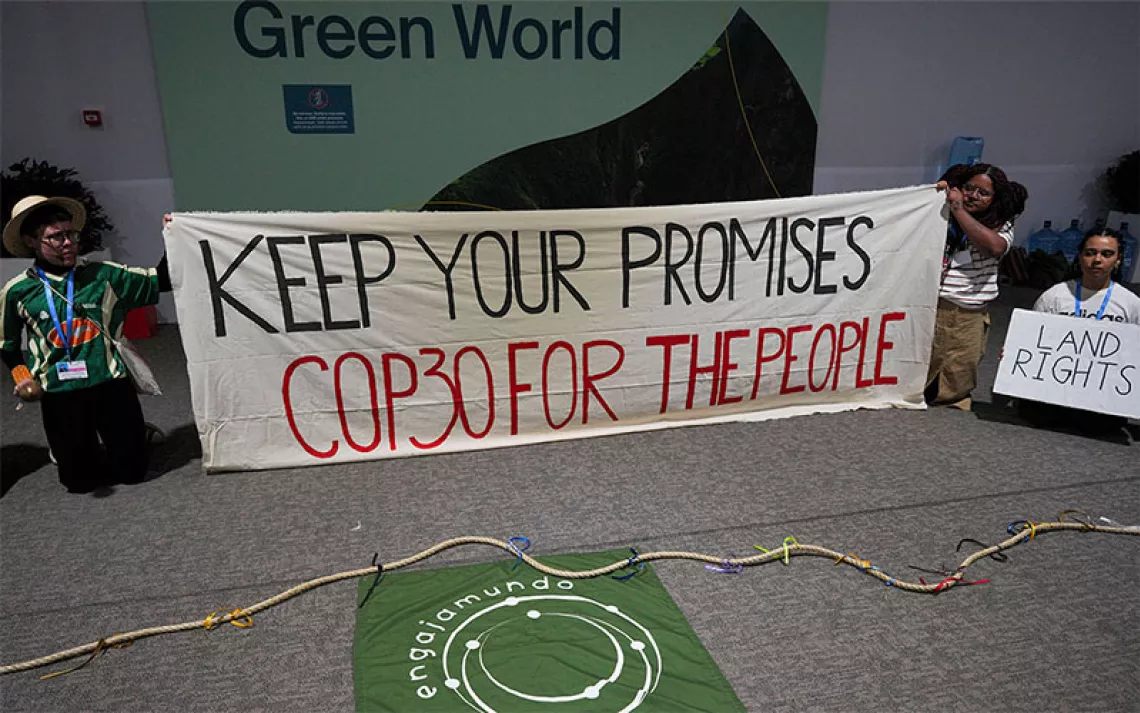

The question of how to balance economic growth with conservation is among the most contentious issues at this year’s biodiversity summit. At the last COP conference in Montreal in 2022, nearly 200 nations committed to protecting 30 percent of the planet to slow down alarming rates of habitat loss and species extinction. This week, delegates from those nations are assessing the status of those goals and what needs to happen to achieve them, including more financial support from wealthier countries. Representatives from European and North American countries have pushed for clarification on the metrics used to evaluate whether countries are on track to meet agreed goals, while countries from the Global South, like Colombia and Senegal, speaking for the Africa Group, have stressed the need for additional funding to meet climate goals.

Indigenous community leaders in Colombia, such as a delegation from the Misak people, have also addressed the importance of their role as custodians of threatened forest regions and stressed the importance of including communities who live in the Amazon region in conservation efforts.

Luz Mery Aranda Velasco traveled from the Cauca department of Colombia with representatives from the Misak people. “Our people are the frontline guardians of these lands,” she told Sierra. “To us, these are our ancestral lands, our culture, our people.” Colombia is the most dangerous country in the world for land defenders like Arana Velasco. Seventy-nine activists were killed in 2023. “[Indigenous people] are risking our lives to protect this precious resource,” she said. “And some of us are paying the ultimate price.”

As world leaders, NGOs, diplomatic personnel, experts, and other invitees attend meetings behind closed doors, downtown Cali has taken on a festival atmosphere. Tens of thousands of people flock to a “green zone” set up near the conference centers. Indigenous musicians, art installations, and informational booths from hundreds of organizations have been constructed from bamboo and wood in a nod to Indigenous homes across the country, and a large stage hosts musical performers from Colombia’s Pacific Coast—which boasts large Afro-Colombian and Indigenous communities.

Many of the organizations are hosting video installations or passing out pamphlets that draw attention to how important Amazon and other rainforest regions in Colombia are to regions across the continent. The Amazon rainforest is the largest carbon-sink in the world, a crucial quality in avoiding climate change. It also regulates water tables in agricultural regions thousands of miles away—a phenomenon dubbed “flying rivers.” The Amazon works like a massive water pump. It pulls in moisture evaporated by the Atlantic Ocean and carries that water inland. As it does, the humidity drops back onto the forest as rainfall. The trees undergo a process called evapotranspiration and the forest returns that rainwater to the atmosphere in the form of water vapor. These flying rivers are atmospheric waterways, often accompanied by clouds, and propelled by the wind from the Amazon Basin to the midwest and south of Brazil and as far north as Colombia, near the Pacific coast. Rising temperatures and deforestation in the Amazon is altering the paths of the flying rivers, a phenomenon that is at least partly responsible for drought conditions in Bogotá and Ecuador.

The 400 billion trees estimated to be in the Amazon release 20 billion tons of water into the air every day. Water from a single tree can fill 10 bathtubs daily, according to the WWF— a major contribution to the region’s flying rivers. Millions of people and huge swaths of agricultural regions across South America depend on that water for ecosystems to function.

Speakers and attendees at COP16 often cite the flying rivers to highlight a key metaphor for this week’s summit. The damage imposed by environmental destruction to Amazon rainforests pulls threads from a complex web that can have cascading and unpredictable effects half a continent away. For those in Cali this week, that’s all the more reason to assure their protection.

The Magazine of The Sierra Club

The Magazine of The Sierra Club