These Scientists Did More Than Tell Us We Were Doomed

The authors of the IPBES report also gave us a road map out

Mangrove forest | Photo by The X File Photo | iStock

For about half a day earlier this week, the news was apocalyptic. “Humans are leading planet into sixth mass extinction” read a typical headline. “Humanity Is About to Kill 1 Million Species in a Globe-Spanning Murder-Suicide,” read another. That news—like all news these days—was quickly superseded by the relentless churn of the news cycle: incredible outfits at the Met Gala; the president squandered a billion dollars.

But it’s important to remember that none of those apocalyptic headlines were really an understatement. They were all based on a summary report released by the UN-backed Intergovernmental Science-Policy Platform on Biodiversity and Ecosystem Services (IPBES)—a committee of scientists who are not prone to exaggeration and who nonetheless concluded that nearly 1 million species currently face extinction because of human actions. It’s also important to remember that the IPBES didn’t just lay a 39-page PDF of doom on us. The committee also offered solutions.

As committees go, the IPBES is on the cautious and conservative side. Like the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC), which released an equally dire climate report last October, it’s made up of volunteer scientists who synthesized nearly 15,000 studies and government reports in order to arrive at their conclusions. Every statement of fact in the summary comes with a note as to how accepted that fact is—as in, “Only 3% of the ocean was described as free from human pressure in 2014 (established but incomplete).”

Unlike the members of the IPCC, which was created in 1988 by the World Meteorological Organization and the United Nations Environment Programme, the scientists who wrote the report study ecosystems, not weather, and their solutions reflect that grounding in landscapes. If you want to call off the sixth mass extinction, according to the summary, this is what will actually work.

Reverse the expansion of monoculture

In 1845, a water mold decimated potato crops throughout Europe and sent a million refugees fleeing Ireland. Those doomed crops were clones of a single potato that had been brought to the country from Peru—but, fortunately, Peruvian farmers were still cultivating thousands of potato varieties, some of which proved resistant to the blight.

This kind of object lesson hasn’t stopped agriculture from drifting further and further toward monoculture. According to the IPBES, over 9 percent of the domesticated mammals used for food and agriculture are now extinct, and twice that percentage are threatened. Seed banks are a worthy attempt to preserve the genomes of different crops and their wild ancestors, but they’re no substitute for keeping land available for them to grow, especially as climate change alters the weather conditions they will need to survive. Regions that are home to crop diversity, like the corn growers of Chiapas, should be supported, valued, and recognized for their contributions to global food security.

Restore and protect coastal marine ecosystems

As the summary puts it, "Coastal marine ecosystems are among the most productive systems globally, and their loss and deterioration reduces their ability to protect shorelines, and the people and species that live there, from storms, as well as their ability to provide sustainable livelihoods (well established).” Wetlands, in particular, are also fantastic at sequestering carbon from the atmosphere.

Protecting these landscapes would probably mean protected status for landscapes like coastal mangrove forests and an end to beachfront resorts and industrial development on the coastline. It could also lead to helping coastlines and wetlands rewild themselves before hurricanes come along and do it by fiat, with a lot more property damage.

Protect fish for real

Protecting fish would mean not only an international crackdown on illegal fishing and hard catch quotas, but also working to keep oceans and the streams that lead into them free of pollution. It also means eliminating the subsidies that many countries (the European Union, Japan, China, the United States, and Russia are among the biggest spenders) give to their fishing industries in the form of tax breaks, cheap fuel, low-interest loans to build new boats, and state-supported infrastructure like ports and processing plants.

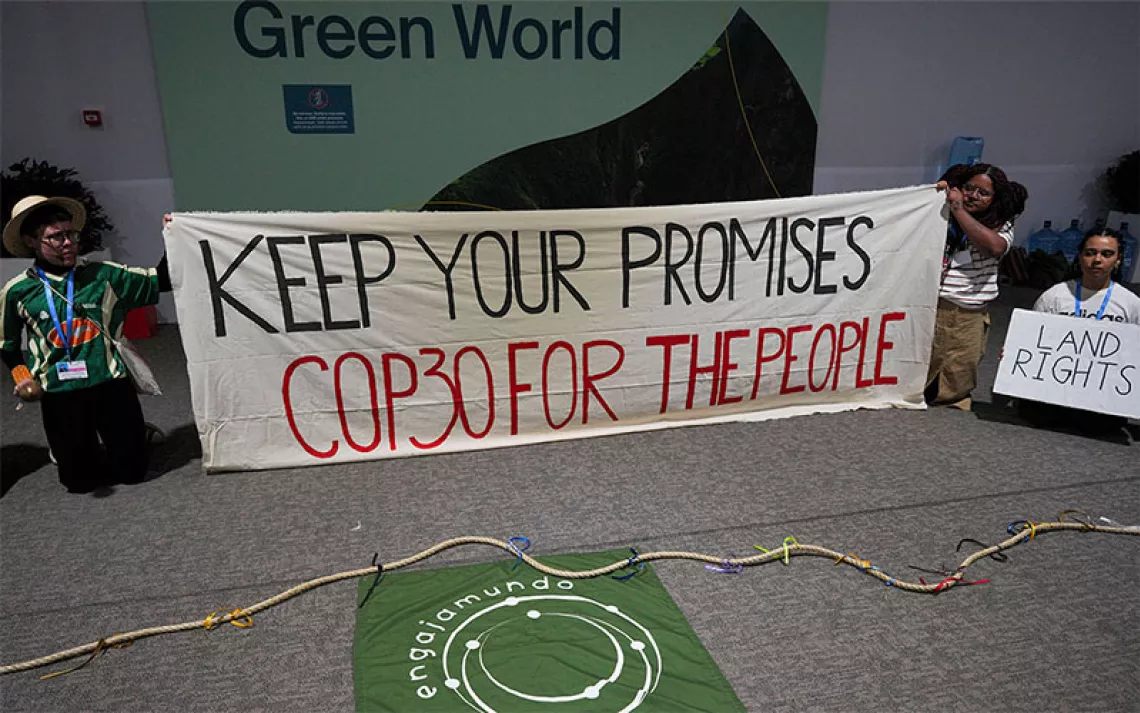

Put Indigenous people in charge

Place them in charge of their own territory (including the oil, gas, and minerals underneath it), but also tap them as collaborators in other local sustainability efforts, since their history of literal dependence on the landscape means they are likely to know better than anyone else what a particular ecosystem needs. Heads of state who threaten Indigenous sovereignty, the way that Brazilian president Jair Bolsonaro has, would find themselves under significant international pressure.

Reconsider roads

When paved roads go into formerly roadless areas, they increase the likelihood that outsiders can come in and strip an area of natural resources. Since it’s easier to not build a road than it is to police that road, letting wild areas remain roadless is one of the cheapest ways to keep an ecosystem relatively intact.

Make life good for everyone

At several points in the summary, the IPBES describes “ever-increasing material consumption” as a concept that is incompatible with leading a good life in the future. Instead, they say, addressing inequality, lowering consumption, expanding access to education, and supporting sustainable technology are our best bet for relieving the pressures that lead to illegal logging, poaching, overfishing, and generally living beyond our means.

These goals may seem more than a little idealistic. But then, every solution to climate change and loss of biodiversity has to be based on ideals, because our current reality is not cutting it. The world’s nations aren’t doing enough, even if they manage to live up to the promises they made in the Paris climate agreement.

Teenage climate activist Greta Thunberg refers to the solutions that the world needs in order to avoid complete climate breakdown as “cathedral thinking”: “We must lay the foundation while we may not know exactly how to build the ceiling,” she recently told the European Parliament. Cathedral thinking is what the IPBES has given us.

The Magazine of The Sierra Club

The Magazine of The Sierra Club