United States, Other Greenhouse Gas Emitters Failing to Cut Emissions Fast Enough to Meet Climate Goals

Time for action is quickly running out according to new studies, including the 5th National Climate Assessment

A former section of Lake Mead in Nevada. | Photo by John Locher, AP File

As all signs point to this year making history as the hottest ever recorded, a raft of new reports paint a stark picture of how the world’s top industrial nations are responding. There are limited signs of progress in the effort to phase out the greenhouse gas emissions from human activity driving the climate crisis, and many scientists affirm there is still time for governments and corporations to act. But time is quickly running out.

The studies confirm what many climate scientists have been assessing for months: that despite impressive advances in the adoption of renewable energy sources, the world’s top greenhouse gas emitters are lagging far behind their stated climate goals; warming temperatures are accelerating with impacts felt around the globe; and the planet is on track to breach average temperatures at or above 1.5°C, or 2.7°F, annually for the first time.

The Biden administration has released the 5th National Climate Assessment, a sprawling congressionally mandated, peer-reviewed analysis of the latest data about domestic climate trends from 14 federal agencies with over 800 contributing scientists. The analysis found that the United States, the world’s historically biggest emitter of greenhouse gases such as carbon dioxide and methane, only reduced its emissions by less than 1 percent each year from 2005 to 2019.

Added together, the reduction amounts to a 12 percent total cut during that window of time—certainly a positive outcome—but the pace is not nearly enough to meet national and international targets for climate action. The United States’ official goal is to cut its greenhouse gas emissions in half by 2030 from 2005 levels. To achieve that, the nation’s net greenhouse gas emissions would have to drop 6 percent every year from now through 2030, according to the report—a reduction trend for a major polluting nation that has no precedent in the industrial age.

At the same time, the United States is heating up approximately 60 percent faster than the rest of the world. There is virtually nowhere in the country not experiencing the consequences of that warming. The report makes clear this reality is the direct result of human activity mainly in the form of burning fossil fuels such as coal, oil, and gas for energy. Compounding events such as heat waves, water stress, drought, wildfires, and flooding will become more common in a warming world, leading to billions of dollars in damages and a rise in deaths attributed directly to those events. The assessment includes a report on significant advances in attribution science, or the ability of scientists to show how warming temperatures are supercharging extreme events. Newer observational systems, models, and networks on the ground and via satellite have given scientists a greater ability to identify whether and by how much anthropogenic climate change contributed to extreme weather events or other planetary trends—bigger storms with higher flood risk, warmer winters, hotter summers with more extreme wildfire danger, longer droughts, and sea level rise that poses a risk to coastal communities around the continent.

Weather-related disasters have already resulted in $150 billion in damages per year in the United States. Researchers included a novel analysis in the report of the future economic burden of global warming—everything from insurance rates to rising food prices—and the social instability that could follow.

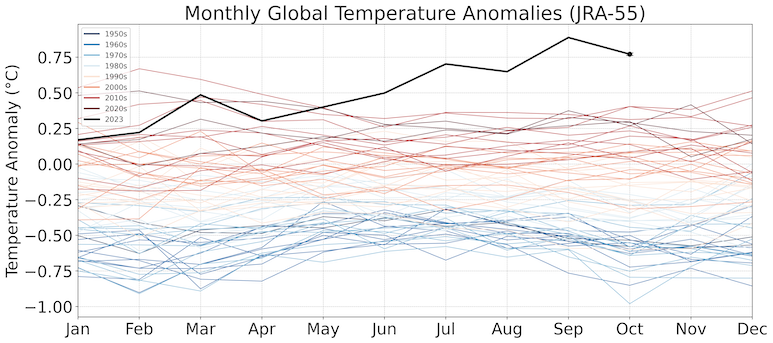

Meanwhile the planet is on a relentless march toward a hotter future. According to recent analysis from Berkeley Earth, it is now virtually certain that 2023 will be the warmest year since records began in the 1800s, and there is a strong likelihood that this could be the first year the planet’s annual average temperature for one year exceeds 1.5°C. Several analyses confirm that October is the hottest month ever recorded, by a large margin, registering an exceptionally high temperature of 1.7°C above pre-industrial levels.

Courtesy of Berkeley Earth

The release of these findings comes just two weeks before the 28th annual United Nations Conference of the Parties (COP28) climate summit gets underway in the United Arab Emirates, where all eyes will be on the most famous climate goal of all: 1.5°C. In 2015, the world’s top emitting nations committed in the Paris Agreement to a goal of trying to limit global annual average temperatures to “well below 2°C” (3.6°F), with a stated benchmark of around 1.5°C. That goal does not refer to an individual year, but rather a long-term average temperature trend over several years. Climate scientists want to see data over at least five years to determine a long-term trend since individual years can bring variation. An El Niño event, for example, can add approximately 0.2°C of warming to the global land and sea average.

But according to Zeke Hausfather, climate scientist and energy systems analyst at Berkeley Earth, it’s a worrying trend. “If you have a big El Niño event like we have today, it gives us a sneak peek of what the new normal is likely to be five to 10 years from now,” he said. “At the rate the earth is warming, we’re adding a permanent Super El Niño worth of heat to the system every decade.”

Hausfather authored Chapter 2 of the 5th National Climate Assessment, which evaluates the time governments have left to ramp up policies that respond to the climate crisis. He maintains that there is still time to avoid the worst-case scenarios that models predict will come to pass should nations fail to act more decisively on their emissions. For example, in a scenario of very high emissions, the planet could exceed global warming of 2°C between 2033 and 2054. In a scenario with low to zero emissions however, the planet could avoid that threshold. Though the analysis notes that a slowdown or cessation of warming does not necessarily mean an end to climate change, as carbon dioxide emitted by human activity will remain in the atmosphere for thousands of years.

"What we want to do now is make sure we don’t make the same mistake and come back 15 years from now saying, well it’s too late to avoid 2° because we didn’t limit emissions in the meantime. We should learn from our mistakes here and not waste any more time.”

Over the past two decades, the emissions reductions in the United States took place without a robust policy framework supporting those reductions, showing that some progress even without legislation is possible. The Obama administration tried to institute a framework in the form of the Clean Power Plan, but political and legal opposition paralyzed it. Meanwhile, clean energy got cheaper, and gas, though still a dirty form of energy because of its methane emissions, increasingly displaced coal, a much dirtier form of energy. Solar is currently the cheapest form of energy in much of the world, and strong climate policies now exist in the United States such as the Inflation Reduction Act, which is catalyzing a massive investment in clean energy systems thanks in part to uncapped subsidies for those systems and their adoption.

But Hausfather noted that time is running out. “We have a vanishingly small remaining carbon budget to limit warming to 1.5°C,” he said. “There’s a growing consensus in the scientific community that we’ve waited too long to reduce emissions and passing 1.5°C for at least a period of time is pretty much inevitable at this point. What we want to do now is make sure we don’t make the same mistake and come back 15 years from now saying, well it’s too late to avoid 2° because we didn’t limit emissions in the meantime. We should learn from our mistakes here and not waste any more time.”

Beyond the United States, studies show other nations are also acting too slowly. Coal consumption globally is at near record levels, accounting for approximately 40 percent of carbon dioxide emissions. And worldwide, fossil fuels still account for approximately 80 percent of all energy generation. A just-released United Nations Environment Programme 2023 Production Gap Report affirmed that “governments, in aggregate, still plan to produce more than double the amount of fossil fuels in 2030 than what would be consistent with limiting global warming to 1.5°C.”

"We can party while the balance of our bank account is going down, but we can’t party forever."

Climate scientists are increasingly sounding the alarm that Earth’s systems are wobbling out of control. In late October, a cohort of 12 internationally renowned scientists released a synthesis report that examined all available data on climate patterns and juxtaposed it with other factors, such as water vapor and El Niño. In their final report, "The 2023 State of the Climate Report: Entering Uncharted Territory,” the authors state that, “Life on planet Earth is under siege” and document the many climate records that were broken this year, including ocean and surface temperatures, sea ice, and the unprecedented wildfire season in Canada that resulted in huge plumes of carbon dioxide emissions. “We are in unchartered territory that humans have never seen before,” William J. Ripple, a professor of ecology at Oregon State University and the lead author of the paper, told Sierra. Ripple was also the lead author of "World Scientists’ Warning to Humanity: A Second Notice," published in 2017, which featured 15,364 scientist signatories from 184 countries. He pointed out that “climate change is just a symptom of ecological overshoot”—when industrial demands for resources exceed Earth’s regenerative capacity.

And according to a cohort of 29 internationally renowned scientists, we have now breached six of the nine planetary boundaries that support life on Earth. A previous cohort first introduced the framework of planetary boundaries in 2009, offering a novel method for evaluating those different systems, including biosphere integrity, climate change, and ocean acidification. The authors defined them as nine thresholds and elucidated the ways in which the transgression of these boundaries would implicate a hard exit from the “safe operating space” for human civilization.

Katherine Richardson, leader of the Sustainability Science Centre at Copenhagen University and the paper’s lead author, says, “Earth is now well outside of the safe operating space for humanity.” Richardson and her colleagues have spent the past 30 years working to develop the Earth systems branch of science that recognizes the planet as a complex, adaptive system in which the interactions between physical, chemistry, biology, and people control the state of the overall environmental conditions of the planet. “What the climate crisis and the biodiversity crisis are showing us is that we need to manage our relationship with the planet as a whole,” Richardson told Sierra. “We, like all other organisms, are supported by the earth’s resources, and the earth’s resources are limited. We can party while the balance of our bank account is going down, but we can’t party forever. That’s the situation that humanity has fallen into.”

According to Richardson, industrial societies around the world would have needed to implement systemic change starting in 1988 to avoid the climate reality we face today—a stark reminder that the world must take action now to avoid an even more dire reality 30 years into the future.

The Magazine of The Sierra Club

The Magazine of The Sierra Club