How Much Longer Can Glen Canyon Dam Last?

Damage to its aging infrastructure raises questions about its ability to release water in a drier future

The outlet tubes of Glen Canyon Dam were opened during the 2004 high-flow experiment on the Colorado River. | Photo by Anne Phillips/USGS

This spring, the Bureau of Reclamation revealed damage to the river outlet works system of Glen Canyon Dam. While there is no structural risk to the huge dam on the Colorado River, the incident drew attention to the dam’s antiquated infrastructure and brought into question its ability to sustain water releases from Lake Powell at lower elevations. At risk are both the lower Colorado River Basin’s ecosystems—including the Grand Canyon—and the 30 million people who rely on the Colorado’s water.

The damage was caused by a High Flow Experiment Release in April 2023, by cavitation, a process that happens when water passing through pipes at high velocity creates air bubbles that cause erosion. During the 2023 release, 3,500 CFS (cubic feet per second) of water was released through the outlet works pipes for 72 hours. The aim was to distribute sediment throughout the Grand Canyon to maintain healthy beaches and riparian habitats.

Photo by Casey Root

Part of the reason Glen Canyon Dam was constructed between 1956 and 1963, in addition to water storage and hydropower generation, was to keep a million tons of Colorado River sediment each year from clogging Lake Mead, 305 miles downstream. Lake Powell, the resulting reservoir that straddles the Arizona-Utah border, flooded 169 miles of the Colorado River in Glen Canyon with 8 trillion gallons of water at maximum capacity. The reservoir is currently at an elevation of 3,577 feet and only 37 percent of capacity, reflecting both the two-decades-long drought and a slight uptick from the last wet winter.

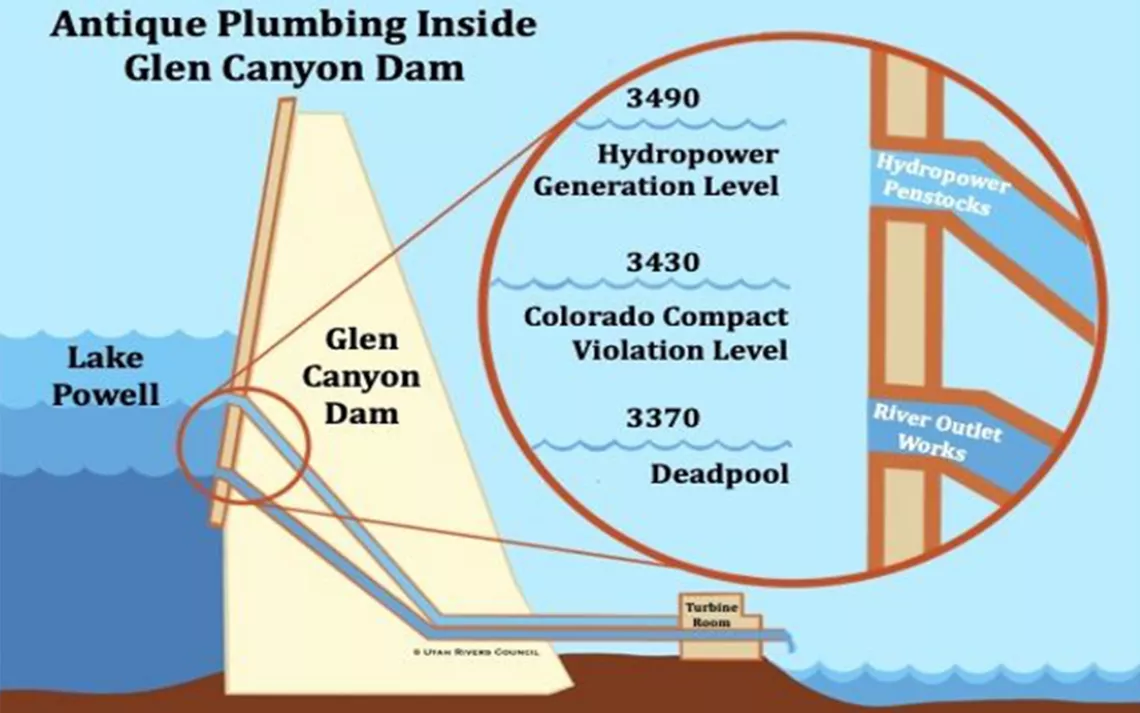

Water is released from the dam through eight main penstocks, which produce hydropower. The four river outlet works are a secondary release option, typically reserved for flood control, High Flow Experiments, and when the power plant is offline. Cavitation, coating, and pipe wall damage were first observed in 1965 following a discharge slightly higher than that of 2023, and the damage has continued over time. While it doesn’t impede the functionality of the outlet works, it does highlight their limitations. Previously, it was assumed the pipes could be used for downstream releases if the reservoir dropped below power pool elevation, 3,490 feet. In an email response to a query, a Bureau of Reclamation spokesperson said that that is not a viable option: “If Lake Powell drops below elevation 3490 feet, Glen Canyon Dam releases could only be accomplished through the river outlet works, which have not been used as the exclusive means to release water and were not envisioned as the sole means to release water from Glen Canyon Dam.”

The bureau is currently running studies and physical modeling to better understand the situation, with an analysis expected by the end of this year. Meanwhile, it plans to replace the interior coating inside the original pipes, which will prevent corrosion but does not address the cavitation. In addition to the $9 million repair, Reclamation will also look to repair the hollow jet valves that regulate water flows through the outlet works.

The damage raises questions about the dam’s longevity. In 2022, environmental groups Great Basin Water Network, Glen Canyon Institute, and Utah Rivers Council released a report, Antique Plumbing & Leadership Postponed: How the Glen Canyon Dam’s Archaic Design Threatens the Colorado River Water Supply. Among their key concerns were the limitations of the river outlet works to release water should reservoir levels plummet. In April 2023, Lake Powell dropped to an elevation of 3,519 feet, the lowest it has been since the dam started filling.

Illustration courtesy of GCI Antique Plumbing Report/Utah Rivers Council

The dam’s future is further limited by the buildup of sediments behind it. During a 2023 presentation, the Bureau of Reclamation slashed the anticipated expiration date for Glen Canyon Dam’s infrastructure from 700 years to a century—which we are already 61 years into.

The groups behind the Antique Plumbing report call on the bureau to stop kicking the can down the road, and to address the serious infrastructure issues—punctuated by the damaged outlet works. “Are we going to have a serious public conversation about how we are going to vet and fund alternatives?” asked Kyle Roerink, executive director of the Great Basin Water Network. “Have there been conversations with Congress about this?”

Jay Weiner, water attorney for the Quechan Tribe in Yuma, Arizona, says that Reclamation is taking informing the tribes seriously and has been proactive in sharing information about the damage to stakeholders. But once more is known, he insists on a collaborative process that includes the tribes. “Reclamation needs to directly engage with us in the decision-making process,” he said. “This is what meaningful and substantive government-to-government consultation means to Quechan and Colorado River Basin tribes. We need to not just be heard but to have tribes’ needs and interests factored into these important decisions. When it comes time to address issues and ramifications of the damage, I would hope and expect a more substantive process among Reclamation, tribes, states, and other stakeholders because Reclamation’s choices may have massive ramifications for the basin.”

Tribal perspectives on all aspects of water management vary greatly. Kurt E. Dongoske, Zuni’s tribal historic preservation officer, expresses concern for the lack of meaningful consultation with Zuni about the high flow experiments that caused the outlet works damage. “Reclamation decides to do these things based on their internal decisions among their inter-agency experts—the tribes aren't part of that—they are notified through email,” he said. “Zuni requested that they become a part of an expert team that makes these decisions on high flow experiments.” Dongoske notes that sand distribution from HFEs can negatively impact archaeological sites in the Grand Canyon, and that concerns from Zuni about management decisions on both sides of the dam are repeatedly ignored by Reclamation.

Potential solutions to the outlet works damage brings attention to the discrepancies between the upper and lower basin state’s visions for how to conserve water and manage less of it. But all parties involved with the Colorado River agree on one thing—that changes are on the horizon. “This is an issue that affects all water and power users below Lees Ferry,” said Roerink. “Will we have a public process for a world where we can’t keep [the water] over 3,490?”

The Magazine of The Sierra Club

The Magazine of The Sierra Club