The Twisted Tale of Indianapolis’s White River

Once considered one of the most polluted waterways in the nation, the White River has been neglected and abused for 200 years. Can it make a comeback?

Frank’s Paddlesport Livery owner Peter Bloomquist paddles a canoe down Indianapolis's White River. | Photo by Robert Annis

First-time visitors to Indianapolis might look at the White River and see a natural oasis in a vast urban landscape. They could spend a day paddling through some of Indianapolis’s most populated neighborhoods but not see another person on the water. Towering oak trees line the banks for much of its path through the city, in the summer offering some needed respite from the sweltering sun. Underneath the clear water, visitors might see dozens of carp, sunfish, and smallmouth bass dart beneath their boat as a blue heron stands in the shallows, waiting for its next meal.

This idyllic scene is just the latest chapter of the White River saga, which has almost as many twists and turns as the waterway itself: Historic blunders. Massive pollution. Unchecked environmental racism. A $2 billion infrastructure project called DigIndy promises to solve many of the problems facing the river. But as the pollution decreases, city officials’ desires to use the river as an economic driver and recreational amenity continue to increase. After years of living next to polluted waterways, the questions for the surrounding residents are now: Will they be able to afford to stay and enjoy the revitalized river? And with other contaminants continuing to flow into the water unchecked, combined with centuries of neglect and abuse, just how clean is the river actually?

Known as the Wapahani by the Indigenous Miami Nation, the White River was a major reason European settlers laid the foundations of Indianapolis here more than two centuries ago. After quickly realizing the river was too shallow for shipping goods, they found other, ultimately much more damaging, ways to utilize it.

Almost from the start, Indianapolis sewage discharged directly into the river, along with industrial waste from factories and slaughterhouses. As the city grew, so did the amount of pollution, becoming a problem that generations of officials believed was too big to solve, a mindset that would continue into the 1980s and 1990s. Reports from the time described the surface of the river routinely being coated with a “black scum,” while “bubbles of gas rise to the surface,” according to late local historian Paul Mullins.

With the river too dirty to safely swim or recreate in, beginning in the 1920s the city constructed more than 20 public swimming pools—all but one of which were earmarked for white residents only. Black residents had two choices: the Douglass Park pool or Belmont Beach, the city’s unofficial Black beach. The beach was located on one of the most polluted spots on the river, so children often swam in water contaminated by dead fish and human feces.

In the 1950s, Indianapolis constructed a series of combined sewage and stormwater sewers; in the ensuing decades, every time a large rain event would occur, human waste would back up and spill out into the waterways. The stench coming off the river and its tributaries—such as Fall Creek—after a rainstorm was enough to make even the strongest person retch.

After years of mostly white residents on the northside of Indianapolis complaining about their own sewage backups in the late 1980s and early 1990s, the city surreptitiously began piping more than 2 million gallons of sewage annually away from wealthier neighborhoods and into Fall Creek, which drained into the White River. It’s no coincidence the surrounding neighborhoods were inhabited by minority and low-income families. The racist overtones couldn’t be ignored, local historian and advocate Leon Bates told Sierra. That’s when the federal government stepped in.

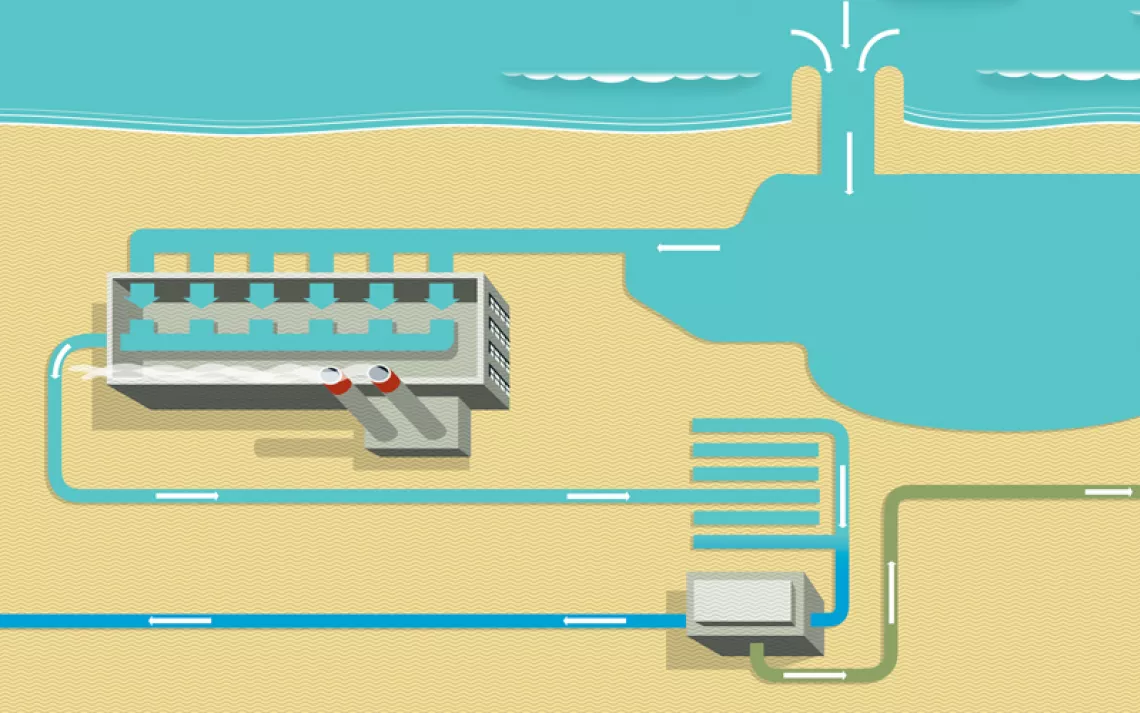

A group of social- and environmental-justice advocates filed a complaint with the Environmental Protection Agency, alleging the sewage issues disproportionately affected minority residents. The EPA agreed, and in 2006 mandated that Indianapolis solve the issues once and for all. In 2011, Citizens Energy Group began to oversee the $2 billion DigIndy project. Six huge tunnels totaling 28 miles would store up to 250 million gallons of wastewater before being treated at the Southport Advanced Wastewater Treatment Plant. DigIndy is slated to wrap up in 2025 with the completion of the Fall Creek and Pogues Run tunnels, the last major sewage-overflow contributors to be remediated.

Residents are already seeing huge improvements. After a massive fish kill in 1999, marine life has returned to the river. Routine volunteer cleanup events help remove tires, old mattresses, and other trash recklessly discarded on and around the river. A canoe and kayak rental shop opened on the banks earlier in 2023, encouraging more people to explore the river. After nearly 200 years of being one of the most polluted waterways in the US, the White River received a C grade for overall health. With E. coli levels still dangerously high, the water is clean enough for boating but not swimming. Most of the experts who spoke to Sierra admitted it likely never will be. And yet, things are looking up enough that along with fish and birds, humans are also returning to utilize the river.

“I’m on the river three or four times a week,” says Ed Fujawa, author of Vanished Indianapolis and a local resident.

In November, officials broke ground on the $13 million Riverside Adventure Park, which will include boat ramps and trails for hiking and biking. And Belmont Beach has also been resurrected, this time as a pop-up park run by the city’s parks department. Talks are ongoing between the city and residents of the Haughville neighborhood about making the site a permanent park.

“[The Belmont Beach] project has always been led by Haughville residents, for Haughville residents,” says Ebony Chappel, Friends of Belmont Beach executive director. “The president of our board is a fourth-generation child of Haughville and I’m third generation.... We’re aware and sensitive to concerns from others in the community, which is why we’re always including their thoughts in the forefront of everything we do.”

Some residents have expressed concern that the much-anticipated river improvements could lead to gentrification. After years of living next to the horribly polluted river, the resulting cleanup and renewal could lead to long-suffering residents being priced out of their homes. Both the city and Haughville neighborhood group are optimistic that won’t happen, but Bates remains skeptical.

“We’ve already seen people get priced out of the neighborhoods” nearby, Bates says, adding that Indianapolis should proactively make efforts to slow or stop widespread gentrification, such as freezing property taxes for long-term Haughville residents until they die or sell the property.

The city’s White River Vision Plan promises to “explore the enormous potential of our river to enhance regional vibrancy, ecological integrity, livability, and economic vitality.” Tourism and city economic officials have traveled as far away as Singapore to study how communities best use their rivers, says Carmen Lethig, a long-range planning administrator for Indianapolis. In the works for riverside developments are plans for a multimillion-dollar retail and entertainment complex centered around a new soccer stadium as well as the new corporate headquarters for a pharmaceutical company. But there doesn’t seem to be much, if any, political will to improve the water quality even further; surface level improvements seem to be enough.

One of the most polluted states in the nation, Indiana has the most miles of rivers and streams deemed too polluted to swim in, according to a report by the Environmental Integrity Project. Pollution from farm runoff—which contains herbicides, fertilizers, and animal waste—and other contaminants continue to flow into the White River from upstream.

Testing should be done daily, says Sierra Club Heartland Group chair Jesse Kirkham, as the pollution levels can vary wildly day-to-day. But water-quality testing by the Indiana Department of Environmental Management in the White River and its tributaries has dropped precipitously over the years for lack of funding. Volunteers with the Sierra Club, White River Alliance, and other groups have picked up some of that slack. Considering its history, the White River’s comeback thus far is nothing short of miraculous, but there’s still a long way to go before a true happy ending can be written.

The Magazine of The Sierra Club

The Magazine of The Sierra Club