What the Thinx Class Action Settlement Means for All of Us

And how to change both your underwear and the law

Photo by Bonny Ghosh/AP

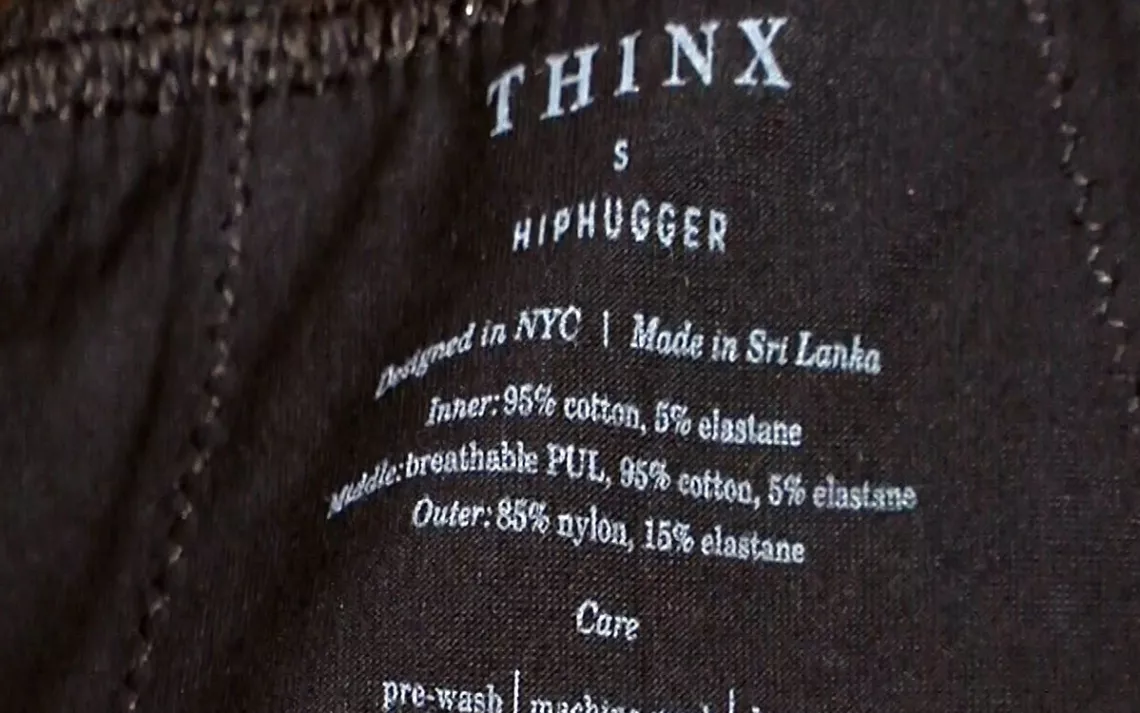

Many readers of this column know that in January 2020, I set out to write a story about which menstrual underwear products were the greenest and least toxic. I contacted all the “organic” menstrual underwear companies I could find to ask if they included PFAS or antibacterial chemicals. When I didn’t get a response from Thinx about their leakproof, organic menstrual underwear, I mailed my own pair (unused, I promise) to Professor Graham Peaslee, a nuclear physicist at Notre Dame University, for independent testing.

Peaslee found that the inside of the crotch in my Thinx organic briefs had 3,264 parts per million (ppm) of flourine (an indicator of PFAS), and their organic Shorty for teens had 2,053 ppm. That was high enough to suggest PFAS was intentionally added.

Thinx consumers united to launch a class action lawsuit in response to the news, and in January 2023, the company agreed to pay up to $5 million to settle. The settlement is the first regarding PFAS in consumer products, though the financial penalty itself won’t be much more than a pinprick for Thinx. Since 2022, Thinx has been majority owned by Kimberly-Clark, which owns major brands of single-use menstrual products, toilet paper, paper towels, and baby and adult diapers in 175 countries. It also owns Kotex tampons, which didn't comply with New York's menstrual products ingredient disclosure. (Cotton tampons often have toxic fragrance and plastic.) Its Cottonelle Ultra, Scott 1000, and ComfortPlus toilet papers, Kleenex Everyday tissue, and Viva paper towels are made from 100 percent virgin trees and are whitened in a way that emits cancer-causing dioxins into our air and water (elemental chlorine free).

Kimberly-Clark reported an adjusted operating profit (which excludes expenses) of over $2.6 billion in 2022. The maximum a Thinx customer gets from this settlement is $21 ($7 each for up to three pairs).

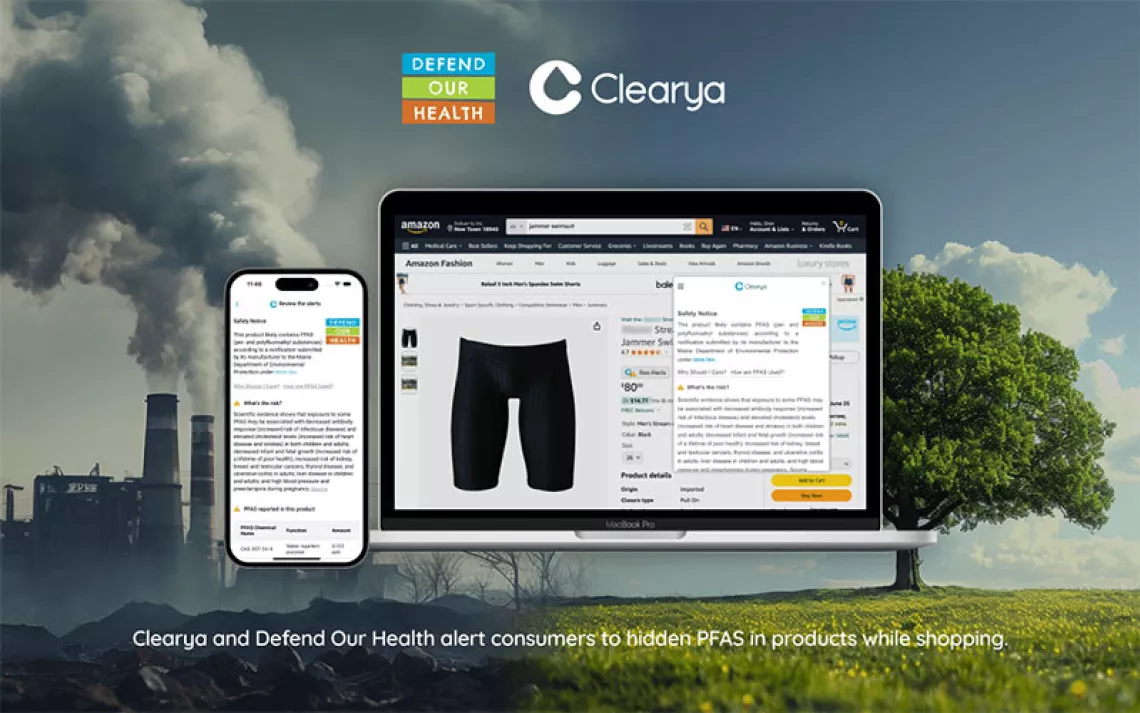

The story of how a company marketed a product with toxic PFAS chemicals as “organic” to consumers has further inspired a mainstream conversation about how PFAS is everywhere, from underpants to food containers, furniture, and baby products—and how companies are using deceptive marketing practices to avoid scrutiny of how those products get made.

Sign up to receive Sierra News & Views

Get articles like this one sent directly to your inbox weekly.

With this action you affirm you want to receive Sierra Club communications and may vote on policy designated by the Sierra Club Board.

But there is a real value in the Thinx settlement beyond money, and it is perhaps the most important outcome of this story. The story of how a company marketed a product with toxic PFAS chemicals as “organic” to consumers has further inspired a mainstream conversation about how PFAS is everywhere, from underpants to food containers, furniture, and baby products—and how companies are using deceptive marketing practices to avoid scrutiny of how those products get made. And it’s a conversation we need to have with lawmakers so we can finally put a stop to the use of these hazardous chemicals.

“This is the first class action case that we are aware of to allege deceptive marketing practices stemming from the presence of PFAS in consumer products,” Erin Ruben, an attorney at Milberg Coleman Bryson Phillips Grossman, who represents the plaintiffs in the class action lawsuit against Thinx, told me. “The settlement was about the marketing of the underwear—not whether it caused harm to consumers. Even if class members decide to participate in this settlement, they are not giving up their right to bring personal injury claims in the future.”

While the settlement is a victory for consumers, and for all those who care about whether and how toxics get into our environment and our bodies, it’s not perfect. What would make it so? A 180-degree pivot from the company at the center of that story: Thinx itself.

“This is the first class action case that we are aware of to allege deceptive marketing practices stemming from the presence of PFAS in consumer products."

Thinx missed an opportunity to play a leadership role in one of the most important issues affecting the lives of millions of consumers. Company leaders could have responded to the news that PFAS was found in its products by launching its own investigation (which would have produced the same result as Peaslee’s), embracing the scientific results with honesty and with its own righteous outrage on behalf of its customers, changing its manufacturing process so that its products were what they said they were—organic—and finally, publicly calling on other companies in its space to follow its lead in order to help make the world a safer, greener place. This was a historic opportunity for a company to learn, along with the rest of us, about toxic chemicals in everyday manufacturing that harm human health, and then take the lead on educating the public and calling for change on its behalf—including state laws that ban these harmful chemicals from our lives for good.

But in the face of that historic opportunity to lead, Thinx demurred. The company just settled without admitting wrongdoing. More important: “According to this Thinx settlement, Thinx said they'd help ensure PFAS is not ‘intentionally added,’ which is different from saying a product doesn't have PFAS,” Bridget Crawford, professor of law at Pace University and author of Menstruation Matters: Challenging the Law’s Silence on Periods, told me. “This settlement and current laws don’t require menstrual product manufacturers to reveal all chemicals in their products or to affirmatively demonstrate product safety, such as thorough product testing for toxic chemicals."

Also, Thinx claimed its products were “free from non-migratory antimicrobial nanoparticles.” But the settlement agreement didn’t require Thinx to remove their potentially unsafe antibacterial nanotech, such as Agion treatments. It only required Thinx to disclose its use and stop falsely saying it doesn’t migrate from their products. Studies by Women’s Voices for the Earth (WVE) showed that hazardous ingredients in menstrual products are not necessarily those intentionally introduced during the fabrication process but rather those found in the materials that make up product components.

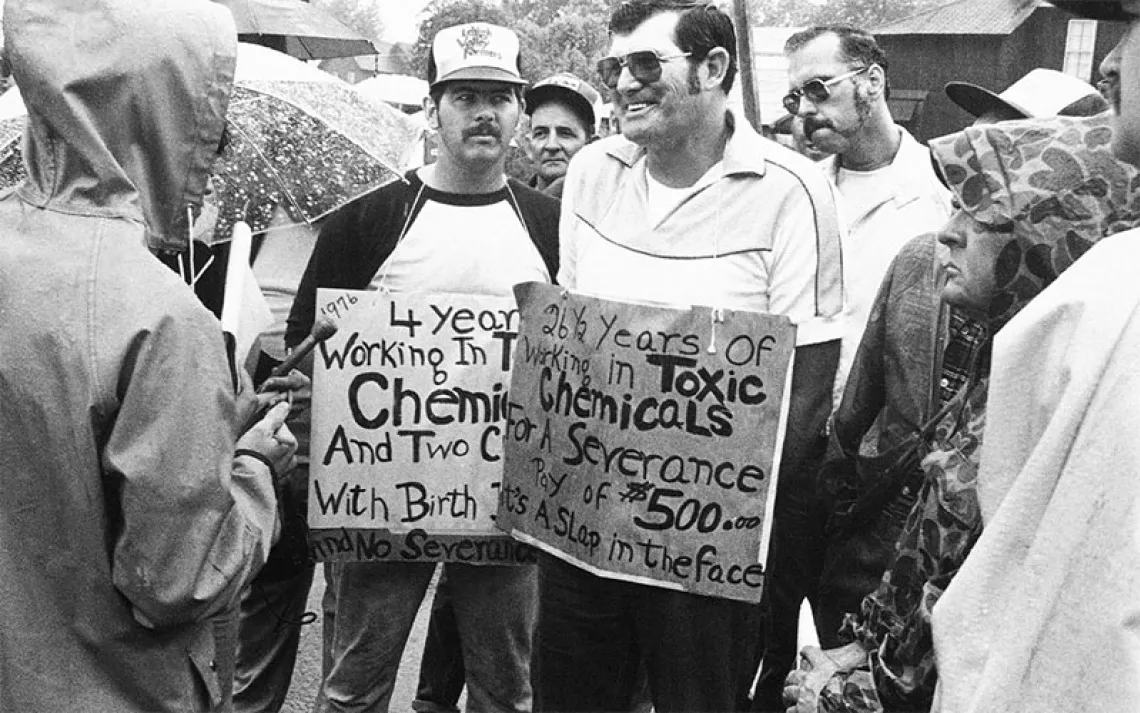

We need more than just a settlement that gives consumers $21 back, or allows a company to continue with business as usual. When it comes to PFAS, business as usual just isn’t acceptable. It shouldn’t be acceptable to Thinx, nor to Kimberly-Clark. It shouldn’t be acceptable to anyone else who is in the business of selling products to people who are just getting by, living their lives and doing the best they can to stay healthy and free of harm, and don’t realize they may be consuming something that actually is harmful to their health.

The hazards of PFAS are real. Exposure to PFOA, a particularly lethal PFAS chemical, has been linked to health problems like an increased risk of cancers, cardiovascular disease, obesity, and diabetes. PFAS also disrupts hormonal functions and may be linked to ovarian disorders like polycystic ovarian syndrome. PFAS do not naturally degrade. And there’s no way to remove them from our bodies.

We need more than just a settlement that gives consumers $21 back, or allows a company to continue with business as usual. When it comes to PFAS, business as usual just isn’t acceptable.

PFAS have been found in everything from clothing and textiles to food and drinks like orange juice and drinking water, toothpaste and floss, contact lenses, hair spray, nail polish, and many things that are resistant to stains and liquids. The chemicals are particularly good at repelling water, which is why they are used so often to make products water-resistant and to create nonstick surfaces for such things as cooking pots and pans.

If companies like Thinx don’t want to help lead us to a greener, less-toxic future, it will be up to the states to create that ethic in laws that ban these chemicals. In California for example, starting January 1, 2025, textiles can’t have PFAS at or above 100 ppm (or above 50 ppm in 2027), even if PFAS is not intentionally added. Though that law doesn’t require product testing, it was the first state law banning PFAS in textiles.

New York has a law that doesn’t require product testing, but it’s currently the strongest menstrual product disclosure law. “Proposed bills I have seen have lower standards of disclosure and are being promoted by the large period product manufacturers,” Laura Strausfeld, executive director of the nonprofit Period Law, told me. “Laws that prohibit certain contents used in consumer products should be expanded to allow the public to enforce laws and have lawyers' fees covered, when our government is not willing or able to do so,” Crawford said.

Safer States lists proposed bills and how you can get involved locally or nationally. And check the safer brands and tips, such as for textiles and food, and petitions to create a world with less PFAS. And for those of you still looking for safer alternatives to Thinx, Aisle is the only organic menstrual underwear that was tested twice to be free of PFAS by secret shoppers (yours truly and consumer watchdog Mamavation).

In case you were wondering, I still haven’t received the email Thinx customers received on January 12, 2023, on how to file a claim to receive their $21 total. And yes, I checked my spam.

The Magazine of The Sierra Club

The Magazine of The Sierra Club