Up to Two-Thirds of US Groundwater Supply May Contain PFAS

The first-ever predictive model of forever chemical contamination paints a worrying picture of urban water supplies

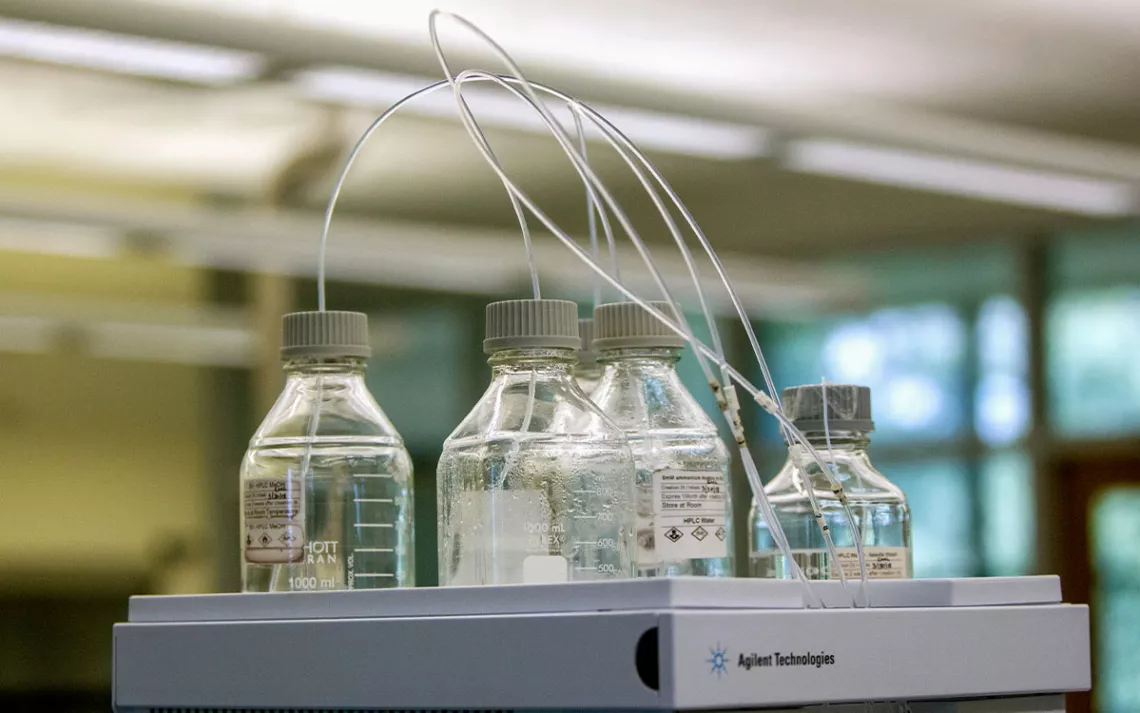

Equipment used to test for perfluoroalkyl and polyfluoroalkyl substances, known collectively as PFAS, in drinking water. | Photo by Cory Morse/The Grand Rapids Press via AP

Nearly 95 million people across the United States could be relying on groundwater contaminated with human-made “forever chemicals,” according to a first-of-its-kind study released by the US Geological Survey last week.

Known as PFAS, or per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances, this category of synthetic chemicals is extremely toxic to human health and has been linked to health problems like kidney and testicular cancers, thyroid disease, and fertility issues. And because PFAS are found in many household items—fabric softener, waterproof clothing, and nonstick cookware, among others—they’ve also begun to seep into our groundwater supply.

Though these chemicals have long been detected in drinking water, the October 24 USGS study is the first-ever source of national estimates for PFAS occurrence in groundwater. Researchers analyzed chemical data from over 1,200 groundwater samples across the nation and used this data to build a predictive model. The model uses variables like population density and well depth to predict the likelihood of PFAS showing up in the groundwater of a given region—even in areas where the USGS hasn’t taken groundwater samples before.

“It's really the first predictive model where we can actually look at unmonitored locations,” said lead study author Andrea Tokranov. “There's a lot of land area where we've never looked at the groundwater underneath, and so this is the first predictive model that actually gets at that and allows us to direct resources [toward] a problematic area.”

Overall, the model estimates that between 50 and 66 percent of the nearly 145 million Americans who rely on groundwater could be ingesting PFAS on a daily basis. But the number one predictor of PFAS contamination is urban land use, according to Tokranov. Some of the nation’s most highly urbanized regions, such as Florida and Southern California, had the highest likelihood of contamination in the public groundwater supply. States along the densely populated Eastern Seaboard were also found likely to draw from contaminated wells—over 80 percent of private groundwater wells in Connecticut, Rhode Island, and New Jersey were estimated to be contaminated with PFAS, and up to 98 percent of the public water supply in Massachusetts saw predicted contamination.

Forever chemicals are human-made, so while researchers can’t always pinpoint where they’re originating from, Tokranov said factors like urban development and population density are “a good indicator of our footprint on the environment”—and a sign of possible chemical contamination.

The October 24 study adds to a growing body of evidence that urban areas are more vulnerable to contamination from forever chemicals. Last year, the USGS released another analysis of PFAS in tap water that found a similar trend: Urban areas had only a 25 percent chance of not detecting PFAS in tap water, while that number rose to 75 percent for rural areas. Another study, released in 2020 by the Environmental Working Group, found that high PFAS concentrations in drinking water were much more common in major metropolitan areas.

In April 2024, the Environmental Protection Agency imposed the nation’s first-ever limits on PFAS in drinking water, mandating that water utilities test and treat their water supply for these chemicals. But the limits have drawn legal pushback from utilities, who say the EPA is overstepping its authority and placing the burden of costly water treatment on industry groups. The EPA limited PFAS concentrations to no more than four parts per trillion, though the National Institutes of Health found that these chemicals can cause adverse health effects at even lower concentrations.

Sign up to receive Sierra News & Views

Get articles like this one sent directly to your inbox weekly.

With this action you affirm you want to receive Sierra Club communications and may vote on policy designated by the Sierra Club Board.

The new USGS study could also help bring more clarity to those who source drinking water from private wells. “When you're in a city, the public water supplier is routinely testing for PFAS. But private well owners, they don't necessarily do that,” said Tokranov.

Private and domestic groundwater wells are often much shallower than public wells, and the study found that shallower wells typically had a higher probability of contamination—the closer to the surface a groundwater source sits, the easier it is for chemicals to seep into that source. The USGS model produced separate estimates for public and private wells, and users can access predictive data for both estimates via an interactive map.

The rate of uncontaminated water filtering into the groundwater supply was also a major predictor of PFAS concentration, the study found. Just as PFAS can seep more easily into shallow wells, this contamination can be offset in areas where clean rainwater seeps into the ground, diluting out toxic chemicals. Tokranov and her colleagues tracked this dilution using a recharge value for each area. In regions with high recharge values, where more clean water is being used on the surface, PFAS concentrations in groundwater were overall found to be lower.

But in regions that used repurposed or imported water—supplies that had already come into contact with human manufacturing—recharge values were often lower, and PFAS contamination was more likely. “In places like California or other arid regions, those are places that suffer from not having quite enough water availability,” Tokranov said. “On the East Coast, where it's humid and it's wet and we have tons of rain, we weren't seeing those trends in the model.”

Tokranov and her colleagues hope to use these regional PFAS predictions to inform their work going forward. By pointing out previously untested areas that are likely to see contaminated groundwater, the predictive model provides a crucial road map for policymakers and citizens alike, she said. “This model is providing information to underserved domestic and private well owners that might not otherwise have a whole lot of information about water quality in their region,” she said.

The Magazine of The Sierra Club

The Magazine of The Sierra Club