A Toxin in Every Household

PFAS face government roadblocks to EPA regulation, but states are fighting back

Photo by eugenekeebler/iStock

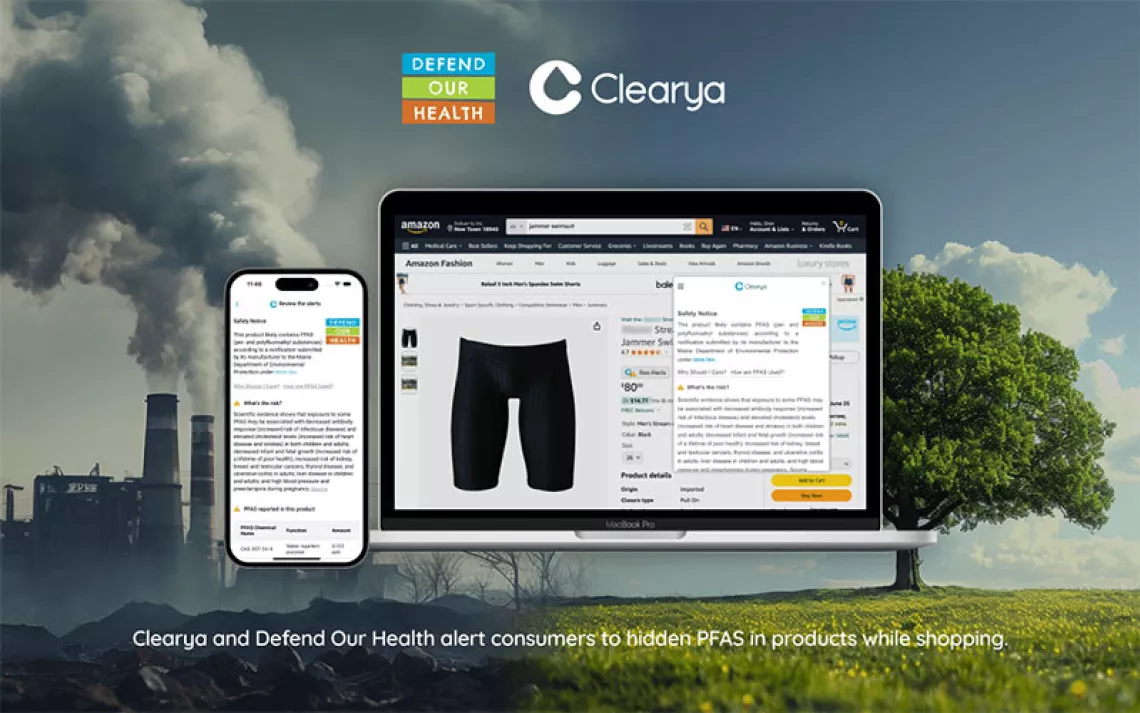

When was the last time you looked around your kitchen or bathroom for chemicals that are toxic to your health? In many households, those chemicals don’t just come in the form of liquid products like pesticides or bleach. They often can be found in the most common items, like frying pans used to cook up a morning egg, or in that popcorn bag heating up in the microwave. That’s because a class of highly toxic, long-lasting chemicals called perfluoroalkyl substances (PFAS) has become ubiquitous in American products.

PFAS have been used in U.S. households since the 1950s, when it was first marketed in Teflon cookware by DuPont. Today, PFAS are added not just to nonstick pans, but also to water-resistant clothing, grease-repelling fast-food wrappers, stain-proof carpets, and other products. Its unusual resistance to degradation is what makes PFAS so damaging to human health and the environment: Decades of study have shown that accumulation of PFAS in the bloodstream can cause various cancers and birth defects. Yet the Trump administration is reluctant to make the dangers of PFAS, and their common use, widely known to the American public.

In January, the Trump administration tried to suppress a report about PFAS that was conducted by the Agency for Toxic Substances and Disease Registry (a division of the EPA)—the latest instance of the administration’s predilection for scientific censorship. An internal aid stated that public knowledge of PFAS toxicity and their use in consumer goods would create “a public relations disaster.” Six months later, in June, the ATSDR released the report, which conclusively links PFAS to a host of harmful side effects and recommends lowering the EPA’s current nonenforceable risk level to 12 parts per trillion, down from 70 ppt (about the size of a drop of water in an Olympic pool).

Sign up to receive Sierra News & Views

Get articles like this one sent directly to your inbox weekly.

With this action you affirm you want to receive Sierra Club communications and may vote on policy designated by the Sierra Club Board.

The report links PFAS exposure to liver toxicity, immune disruption, and developmental problems. In court cases against chemical manufacturers, plaintiffs and medical studies have also linked PFAS in drinking water to kidney cancer, testicular cancer, thyroid disease, ulcerative colitis, pancreatic cancer, and birth defects. “It’s an unusual list of chemical effects,” says Sonya Lunder, senior toxics policy advisor at the Sierra Club. “It’s hard to tie that all together—it’s affecting multiple parts of the body in different ways.”

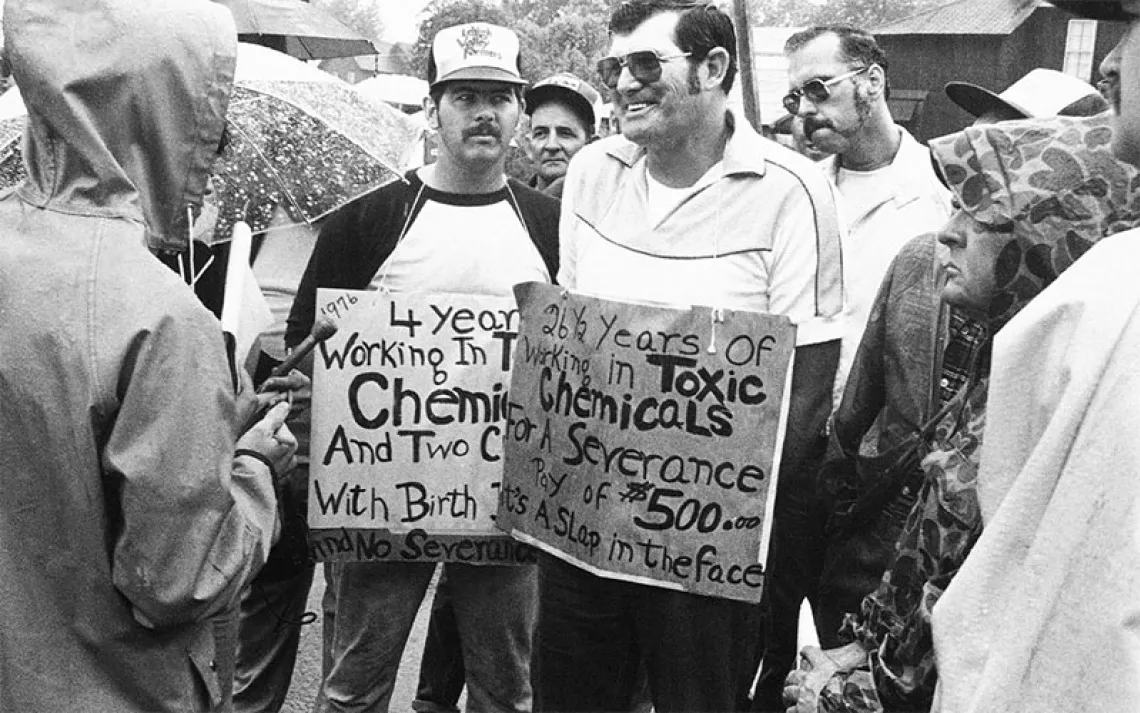

Exposure to PFAS isn’t only limited to household products, and their presence in drinking water has led to intense litigation. Thousands of people who live near manufacturing plants owned by companies such as 3M and DuPont have reported water toxicity levels exponentially higher than the EPA limit, often sourced from storm runoff that seeps from chemical plants into the ground—or, from illegal dumping directly into rivers and creeks. In the absence of federal regulation, numerous states have sued chemical manufacturers that produce PFAS for damages to public health and the environment. Minnesota filed a lawsuit in January against Wolverine World Wide to recoup the cost of PFAS cleanups and municipal water installations for contaminated wells. In February, North Carolina sued Chemours, a spinoff of DuPont, for failing to take action after rainwater runoff mixed with GenX and contaminated the Cape Fear River. In that same month, Ohio sued DuPont and Chemours for contaminating waterways with PFAS used to make Teflon and for withholding knowledge of PFAS’ dangerous side effects from the public.

These lawsuits are not without precedent, and some have already been successful. In 2017, DuPont settled a class action lawsuit in West Virginia for $671 million, in reparations for 3,550 personal injury cases in the state over contaminated water and cancerous side effects. In February of this year, 3M settled a lawsuit with the state of Minnesota for $850 million, after eight years of litigation over PFAS that had leached into public drinking water as a result of making Scotchgard.

Despite these cases and the evidence they present, PFAS remains unregulated, and the path to controlling their production faces a troubling obstacle. The U.S. Department of Defense uses PFAS as a critical component in firefighting foam at military bases throughout the country, where it’s used to put out jet fuel explosions and in demonstrations for navy training exercises. Compounding this, the cost of waterway cleanups and carbon filtration in contaminated cities would net an estimated $2 billion—all from the Department of Defense’s budget. To protect its relationship as a supplier for the DoD (and defend against the massive litigation in West Virginia), in 2001 the chemical industry created the Fire Fighting Foam Coalition, a lobbying alliance of chemical manufacturers and distributors. The FFFC has spent years making persuasive presentations to the EPA and the military, arguing that PFAS are not only nonhazardous, but also necessary for domestic security.

Today, 99 percent of Americans are predicted to have PFAS in their bloodstream, where it is passed on to newborn babies. The Environmental Working Group estimates that more than 1,500 drinking water systems across the country, serving at least 110 million people, are contaminated with PFAS.

The solution to PFAS regulation should not hinge on the outcome of case-by-case litigation. As high as DuPont’s $671 million settlement with West Virginia sounds, it was a drop in the bucket compared to the company’s $79.5 billion revenue for the year of 2017. Regulating PFAS by individual chemical, and not class, is also untenable: GenX was created by DuPont directly in response to the EPA banning production of PFOA, the main chemical in Teflon; the new class is just different enough from PFOA to escape regulation but with all the same side effects. “PFAS has to be regulated as a group; we can’t just ban one or two chemicals and watch the industry shift to another similar one,” says Lunder. “We need to stop all unnecessary uses of these chemicals in new products. It’s not for [city and state] water districts to go bankrupt cleaning up the water [of contaminated regions].”

One step to fighting PFAS production is to raise awareness in communities where chemical manufacturing plants are, and to ensure that the public has legal representation to fight back—and demand that elected officials prevent chemical companies from producing them in their states. The Sierra Club is working with environmental lawyers and county officials in North Carolina, Colorado, and other states where PFAS are produced, with the aim of ensuring that every affected citizen is aware of and armed against the toxic secret living in their environment.

“We are taking the veil of secrecy off this,” says Lunder. “Facilities need to be reporting their PFAS use and emissions into the environment. Pollution is profitable, but [with the] price tag of these cleanups, it’s not viable.”

This article has been updated since publication.

The Magazine of The Sierra Club

The Magazine of The Sierra Club