Extreme Heat Fueled by Climate Change Punishes Outdoor Workers

As the federal government pushes for national heat protections, some states resist badly needed safety rules

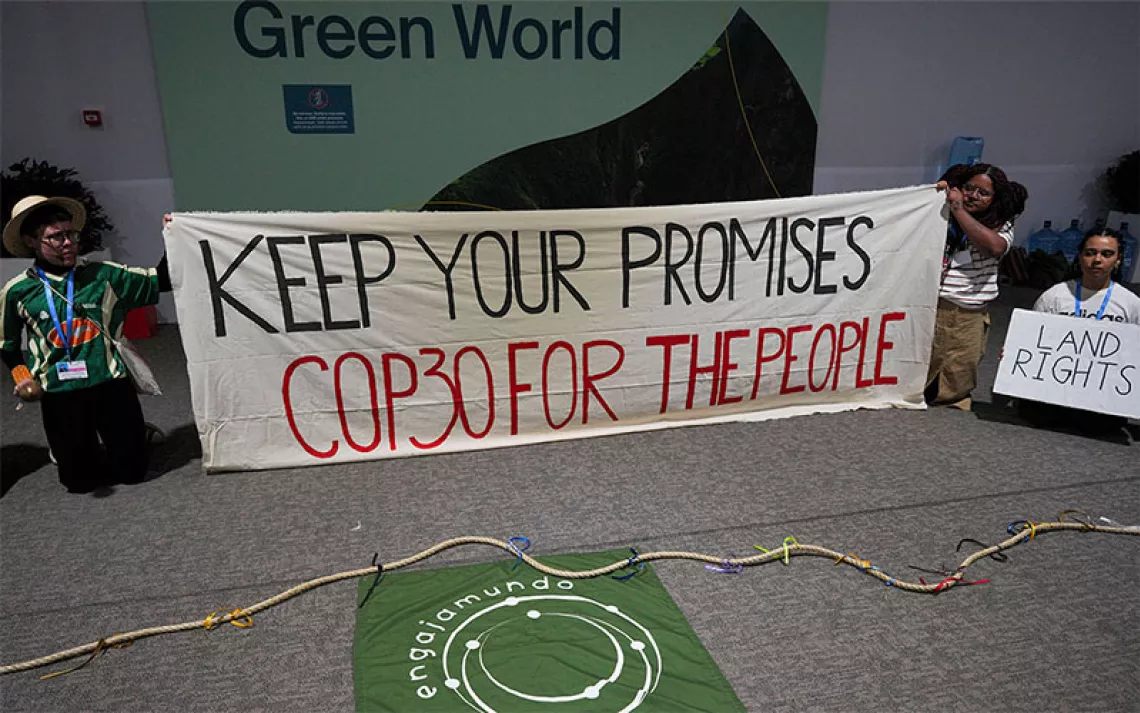

Heat waves that come early in the summer can spell danger for farmworkers because their bodies haven’t acclimatized to the high temperatures. | Photo by Etienne Laurent/AFP/Getty Images

BY 11 A.M. on a Thursday in late June, the temperature in south New Jersey was in the 80s, though with oppressive humidity squatting over the area, it felt like 92°F. It was the first scorching-hot week of the summer, but barely any skin showed on the two dozen men working their way down a row of Sheppard Farms zucchini plants, their torsos protected from the sun and their legs from scratchy leaves and biting horseflies.

Harvesting calabacita, as the Mexican crew call the fruit, requires some delicacy. Rodolfo Najera, a creased man of 59 with white-flecked black eyebrows the size of dill pickles, bent down nearly to the ground, pushed aside leaves, located a zucchini—one that wasn’t too small to harvest or so large that it had become basura, or garbage—and then carefully cut it close to where the vine met the fruit to preserve the rest of the plant. He straightened up and quickly moved on to the next plant.

After the rows were harvested, I asked if any of the workers had ever gotten heat illness doing this work. “Todos,” they replied: everyone. They recalled dry throats, headaches, and intense nausea. Harvesting corn is the worst, they said; the tall stalks make the air so stifling that they feel like they can’t breathe, and they sweat all the way through their clothes.

New Jersey heat waves usually hit in July, but a heavy one had moved in for nearly a week, unusually early and long. Early heat waves can spell danger for people who have to work in hot conditions because their bodies haven’t acclimatized to them. Between 50 and 70 percent of outdoor heat deaths happen in the first few days of exposure at work. Heat illness can be mild, starting with cramps or a rash. The real danger is when someone starts to suffer from heat stroke, when their body can no longer regulate its temperature. That leads to confusion, lightheadedness, vomiting, and passing out. Without treatment, people die.

“Heat is often called the silent killer,” said Kristina Dahl, a climate scientist at the Union of Concerned Scientists. Extreme heat kills more people by far than any other effects of climate change. The situation is getting worse as the planet warms and heat waves come earlier and are hotter and longer.

Protections for people working in heat are simple: After acclimatizing, workers need access to water, shade or somewhere cool, and rest. “There’s no rocket science here,” said Debbie Berkowitz, who worked at the Occupational Safety and Health Administration for six years and is now a fellow at Georgetown University’s Kalmanovitz Initiative for Labor and the Working Poor. Some employers implement the right protections. “Unfortunately,” said Travis M. Parsons, the director of occupational safety and health at the Laborers’ Health and Safety Fund of North America, “a lot of employers out there don’t do it unless it’s required.”

“The tools are there, and the needs are simple,” Dahl said. It’s the politics that get in the way.

Federal and state governments have been slow to put protections in place. In July, the Biden–Harris administration released a proposed OSHA heat standard that, if finalized, will cover nearly 36 million workers. But finishing a new OSHA rule is a laborious process that involves seven stages, each with its own set of steps; a rule can easily take eight years or longer. “The burden for the agency is very high,” Berkowitz said. Congress could speed up the process by passing the Heat Illness, Injury, and Fatality Prevention Act, but last year the bill didn’t get any House hearings or votes.

A smattering of cities and states have their own heat-related protections. California and Washington have standards for outdoor workers, while Minnesota has them for indoor ones and Oregon has protections for both. California added indoor workers in June, although it exempted prisons. A handful of other states, including New Jersey and Maryland, are working on similar protections.

But both Florida and Texas, states with searing temperatures, have moved in the opposite direction, recently passing laws blocking cities from instituting protections. Texas’s law rolled back mandated breaks in Austin and Dallas. Florida’s law prevented a heat-protection standard in Miami-Dade County from going into effect.

Industry is fighting hard against heat regulations. At a recent hearing on New Jersey’s bill, 90 percent of the people who showed up represented employers who opposed it. The New Jersey Farm Bureau is pushing for an exemption for agricultural workers, and it is “going to probably get it,” said New Jersey senator Joseph Cryan, the bill’s sponsor. This carve-out and others could be crucial to helping him get the votes, he said. Cryan hopes to cover all workers down the road. “It’s too damn hot out not to improve working conditions,” he said.

The field hands at Sheppard Farms are relatively lucky, with a boss who provides some protection. A huge machine, called a harvest aid, moves with them and has two large plastic jugs on it: an orange one with water and a blue one with ice, plus a pile of paper cups. If those run out before lunch, they get refilled, a system that’s uncommon on most farms. The workers get designated breaks halfway through the morning shift and halfway through the afternoon, plus an hour for lunch. If someone feels sick, he can cool down in a nearby air-conditioned van. In the farm’s front office hangs a poster from OSHA: “Water. Rest. Shade.”

Few of the field hands took a moment to drink water until the work was completed, and then only two grabbed cups. In heat like this, Tom Sheppard, the owner, allows men to stop working after the morning shift. But they all planned to head back out that afternoon, when temperatures would likely climb into the high 90s, to earn more money.

Sheppard, who took over from his father and today sells his produce to grocery chains and wholesalers, probably wouldn’t mind federal- or state-mandated heat rules, he said, because he’s already doing most of what would be required. “You take care of the people who are taking care of you,” he explained. But it doesn’t come for free. The air conditioner for one of the two housing barracks had recently broken, and it was going to cost about $4,000 to replace.

Air conditioning is a luxury most farms don’t afford their workers. On southern New Jersey farms, “Air-conditioned housing is unheard of,” said Lori Talbot, who ran an area clinic for farmworkers for 40 years. Water and breaks are also rare: Some supervisors put water on the far side of a field and don’t let workers get a drink more than once. Some of Talbot’s patients had gone to the emergency room for heat exposure, and she knew a handful who had died.

By noon, it had climbed to 86°F in a cucumber field as men raced down the rows. The workers’ pace was driven by how they’re paid; the men are guaranteed a minimum wage but can earn an additional $1.10 per packed carton. They worked in silence, with only the sound of swollen cucumbers thudding into knee-high buckets—which they had to hoist onto their shoulders to empty—and their clothes were drenched in sweat. No one paused for water. They dispersed immediately after the work was done, racing into the waiting vans to get to the air-conditioned barracks for lunch.

The Magazine of The Sierra Club

The Magazine of The Sierra Club