August Stargazing: Billionaires in Space

Amid the infinite void of space, a billionaire is nothing at all

Jeff Bezos during a post-launch news briefing on July 20, 2021. | Photo by AP Photo/Tony Gutierrez

Last month, as Jeff Bezos’s phallus-shaped rocket thrusted toward the heavens, reporters clamored to cover the story. He and his crew’s space flight lasted all of 11 minutes, four minutes shorter than the first manned space mission 60 years ago, when Apollo 11 astronaut Alan Shepard spent 15 minutes in orbit.

Bezos may be new to space exploration, but he undoubtedly knows his way around a press conference. The post-flight theatrics proved far longer than the actual flight, as Bezos, bedecked in a blue jumpsuit and tattered cowboy hat, presided over the ceremonies. Anchors from CBS’s This Morning program played astronaut as they read their lines in front of a backdrop of Earth from space. Meanwhile, CNN covered the mission for several hours, including unfiltered coverage of the post-flight press conference.

The event was mostly a self-congratulatory spectacle, complete with Bezos’s counterattack on his critics—people he deemed “vilifiers” as opposed to “unifiers”—followed by an announcement of a new “Courage and Civility Award,” which consisted of giving $100 million apiece to CNN contributor and progressive activist Van Jones’s Dream Corps organization and chef Jose Andres. Perhaps Bezos felt obliged to “go big” since one of his space rivals had already beaten him to the punch. Days earlier, Virgin Galactic founder Richard Branson joined a crew inside a specially designed rocket plane that surged 50,000 feet above Earth’s surface. Branson unstrapped himself and floated in weightlessness for a few brief moments. The contours of Earth could be seen through the windows of the craft, which resembled the interior of a futuristic private jet. Mars-colonization booster Elon Musk, for his part, has not yet taken a joy ride on one of his company’s rockets, instead focusing his efforts on blasting provocative messages into the Twitter-verse.

What Bezos and Branson accomplished can hardly be called revolutionary from a technological standpoint. For more than a half century, humans have been going to space, to greater heights and for far longer periods of time, carrying out spacewalks and experiments on space stations. Unlike NASA’s public, taxpayer-financed mission, the space exploration that Bezos and Branson are embarking on is a for-profit venture. They're looking to make a buck selling tickets—from tens to hundreds of thousands of dollars apiece—to wealthy adrenaline junkies seeking the roller coaster thrill of low orbit flight. Bezos, whose company Blue Origin is also part of a team working to develop a moon landing craft for NASA’s Artemis program, calls space tourism a necessary step toward building the space infrastructure for future generations.

After last month’s space flight, Bezos’s critics pounced, noting that his and Branson’s sojourns felt like escapism for the ultra-wealthy. Some critics focused on his company, Amazon, and its record of low wages and poor working conditions. “Jeff Bezos was in space for five minutes,” tweeted Daily Show host Trevor Noah, “or as it’s known at the Amazon warehouse, your allotted break time for a 16-hour day.” Others looked at the ecological backdrop of the launches, noting that the billionaire space journeys took place while the planet was being rocked by massive heat waves, floods, and fires. The Guardian noted that each of these rocket rides had deposited hundreds of tons of carbon dioxide directly into the upper atmosphere. The news watchdog Media Matters noted that Bezos’s stunt got almost as much coverage on the three major networks, in a single day, as climate change got in the entire year of 2020.

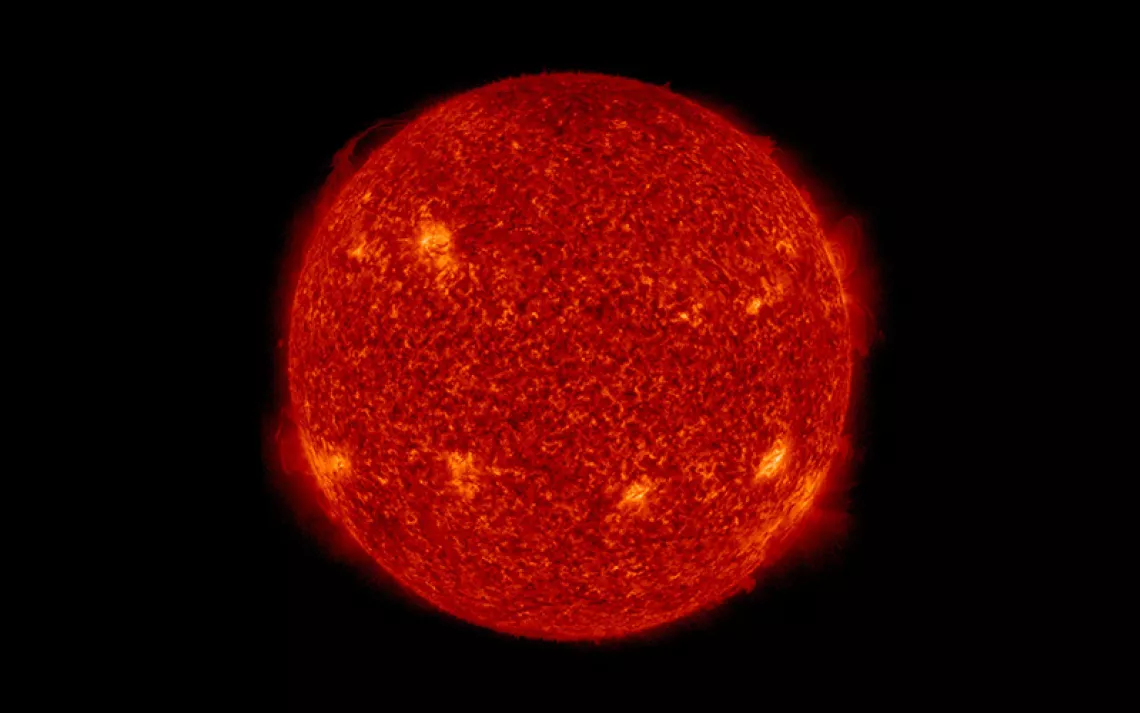

Unlike his fiercest detractors, however, I believe that the tax-dodging Bezos has been unfairly cast as someone with no earthly concerns. Over the years, Bezos has publicly acknowledged the existential threat of climate change. In 2020, he established the Bezos Earth Fund, which committed $10 billion to fighting climate change. After his short jaunt into orbit, Bezos described seeing Earth’s thin, life-giving atmosphere from a space capsule as a life-changing experience. “When you get up above it, what you see is it's actually incredibly thin,” Bezos said. “It's this tiny little fragile thing, and as we move about the planet, we're damaging it.… It's one thing to recognize that intellectually. It's another thing to actually see with your own eyes how fragile it really is." He then expressed his belief that in order to stave off a planetary disaster we need to move all heavy industry off planet and into space.

Let’s assume for a moment that such a feat is technically possible and not mere marketing spin. From an ecological standpoint, outsourcing our polluting industries to a lifeless planet, or mining asteroids for precious metals seems to make some sense. We might not only save the planet but human lives in the process by doing what Silicon Valley has truly excelled at—outsourcing the job to robots.

But those far-off cosmic aspirations sidestep immediate problems that are the result of our rapacious behavior on this planet. When Bezos offhandedly mentions going to other planets to mine raw materials, he is essentially saying that one planet is not enough to sustain us. He would rather use his fortunes to ravage the surfaces of distant worlds than to reform the economic system presently devouring our home planet. Bezos’s big dreams are a tacit admission that free-market capitalism—which requires an endless supply of raw material and cheap labor to sustain its churn of constant growth—has failed us and Earth.

Which brings us back to his reflections on his brief penetration of the veil of space. Bezos talked about how fragile the planet looked to him but never reflected upon how vulnerable he, the world’s richest man, was while he was out there, beyond the protection of Earth’s atmosphere.

Those of us down here on the surface without a ticket, forced to watch on the news feed, could see it clearly though. As Bezos’s space phallus surged toward the heavens, it appeared smaller and smaller until it was little more than a flicker. Then the flicker was gone.

Flung up into the infinite void of space, a billionaire is really nothing at all.

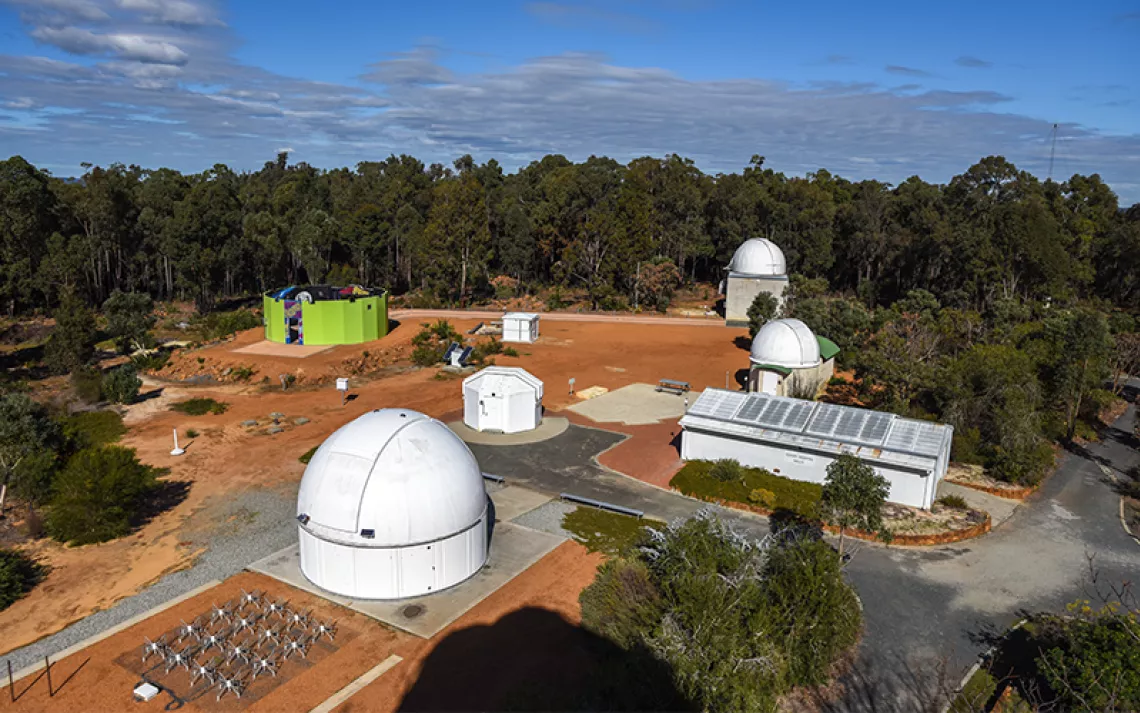

WHAT TO LOOK FOR IN AUGUST

As August rolls in, so too does one of the great annual astronomical sights of the year—the Perseids meteor shower. The shower begins in late July but should peak around August 11 to 13. Meteor-watchers should be able to detect dozens of meteorites per hour by positioning themselves at a dark, wide-open sky location just after midnight and extending to sunrise. The origin-point of the meteors (or radiant, as it’s known in astronomical-speak) is found in the constellation Perseus. The stars that make up Perseus are somewhat dim and hard to make out, particularly from urban locations. An easy way to find the constellation is to look for the unmistakable “W” of the constellation Cassiopeia. From there, draw a line from the left half of the W down toward the horizon. The length of your hand held at arm’s length should put you roughly in the vicinity of the radiant.

While many people have seen the glory of the Perseids, few may know why it happens at all. The individual flashes of light are the product of a comet called 109P Swift-Tuttle, which, according to NASA, takes around 133 years to make a complete revolution around the sun. Discovered in 1862 by Lewis Swift and Horace Tuttle, 109P Swift-Tuttle was last glimpsed in 1992. As Earth passes through the comet’s tail, dust and rocky debris interact with the atmosphere, producing vivid, glowing, and sometimes multicolored streaks of light.

August’s full moon, the Sturgeon Moon, will rise into the sky on August 21. The name, according to the Old Farmer’s Almanac, was bestowed by the Indigenous nations living along the banks of the Great Lakes and Lake Champlain who caught these prehistoric fish in large numbers in the warm months of late summer.

The Magazine of The Sierra Club

The Magazine of The Sierra Club