November Stargazing: Cosmic Collisions

Despite the emptiness of space, objects still manage to crash into one another

Artistic rendering of NASA’s DART spacecraft about to hit the moonlet of Didymos. | Photo courtesy of NASA/Johns Hopkins, APL/Steve Gribben

Last month, a Canadian woman named Ruth Hamilton awoke to a terrifying clatter. Dust wafted from the ceiling and onto her face. Shards of sheetrock covered the sheets. Through a ragged hole in her ceiling, she could see a small swatch of the night sky. She turned to her right and saw, there on the pillow beside her, a strange, dark object.

A meteorite had smashed through her roof and landed mere inches from her head. The 2.8-pound stone was, as The New York Times described it, “the size of a large man’s fist.” If it had entered Earth’s atmosphere at a slightly different angle and landed a few inches to the left, the meteorite likely would have killed Hamilton instantly.

The odds of a meteorite smashing through your roof in the middle of the night are, of course, overwhelmingly slim, one might even say astronomical. You are tens of thousands of times more likely to get struck by lightning (one in 135,000) than by a rock from outer space. There is, in fact, only one documented case of a person being hit by a meteorite—a woman named Ann Hodges from a small town in Alabama who, in 1954, was struck as she reclined on her couch. She survived but received a large bruise from the nine-pound rock, which crashed through her roof, bounced off a radio, and careened into her thigh.

Close encounters like these may be exceedingly rare on human timescales, but beyond our planet, in the vast chasms of space, objects are relentlessly bumping, bashing, and smashing into one another. Over a long enough timeframe, random collisions with Earth become a mathematical certainty. Without them, our planet and, indeed, our entire universe, would be a very different place.

*

Every day, hundreds of meteorites pierce the atmosphere and land on Earth’s surface. Most of these impacts involve pebble-size debris. Occasionally, though, much larger rocks strike the ground. Some of these have left indelible scars. Every year, thousands of tourists stop to gawk at a 150-foot-deep crater near Winslow, Arizona. The depression was created some 50,000 years ago by a meteorite 160 feet in diameter and traveling at almost 30,000 miles per hour. The energy released on impact was equivalent to the atom bombs dropped on Hiroshima and Nagasaki.

The explosion surely devastated the nearby surroundings (and may have triggered a bout of local volcanic activity), but the Arizona meteorite was small in comparison to another object that hit Earth more than 60 million years earlier. That asteroid had a six-mile diameter and slammed into the planet with a force more than a hundred million times greater than the largest atomic weapon ever built. The “Chicxulub impactor,” as it is known, triggered a mega-tsunami that produced skyscraper-size waves, hundreds—perhaps even thousands—of feet high. Massive chunks of the asteroid were thrown skyward then heated to glowing rocky embers as they fell back toward the planet, igniting forest fires as they landed. The impact also threw huge quantities of dust into the atmosphere, interrupting photosynthesis across the globe and altering the climate. The event, which brought the Cretaceous period to a violent end, wiped out three-quarters of all species on Earth, including the terrestrial dinosaurs.

Earth has suffered even larger collisions. According to the giant-impact, or “Big Splash” hypothesis, our Earth and moon formed 4.5 billion years ago when an object the size of Mars (dubbed Theia, the Greek titan and mother of Selene, goddess of the moon) collided with our primordial planet. This collision produced a massive disk of debris, which over tens of millions of years coalesced into the moon. Life on Earth may also be the product of an ancient collision. The “panspermia hypothesis” proposes that the simple organic molecules necessary for life were carried here on a comet or asteroid—perhaps a fragment of a planet—that fell to Earth’s surface.

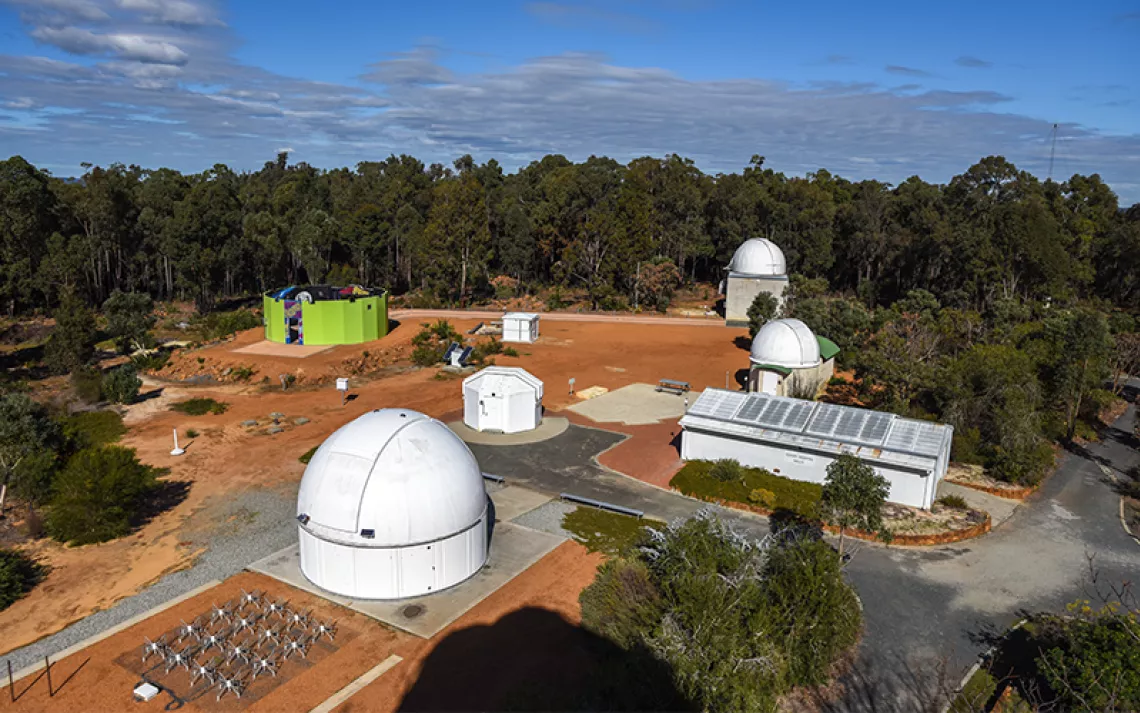

An entire wing of astronomy is concerned with Chicxulub-type asteroids capable of snuffing out life on Earth. Dozens of instruments across the world, including the famed Pan-STARRS telescope on the summit of Maui’s Haleakalā volcano, scour the sky in search of these “civilization killing” objects. Later this month, NASA will be testing a new piece of technology known as a “kinetic impactor,” a small spacecraft that will be aimed at the “moonlet” of a meteorite called Didymos, which orbits the sun on an elliptical path between Mars and Earth. Though the asteroids do not currently pose a threat to Earth, they are of a size class that, if headed toward our planet, would cause serious harm. The Double Asteroid Redirection Test, DART for short, will slam a spacecraft into the moonlet’s surface at close to 15,000 miles per hour to try to change its trajectory.

When you consider the overwhelming size of the universe, it seems improbable that anything would ever bump into anything else. Gravity, however, puts its thumb on the scales, causing distant objects to be pulled toward each other. Even the largest, most distant objects in our universe, galaxies, are subject to this fundamental force—and sometimes they even collide.

Hubble and other powerful telescopes have revealed dozens of these “interacting galaxies” mid-crash. One of the most beautiful pairs is NGC 4674, the “Mice Galaxies,” being warped by their overwhelming gravitational attraction to one another. One spiral arm is in the process of being torn from its moorings, trailing behind like a tattered banner. The most fascinating part about these interacting galaxies is that when these enormous structures come together, very few, if any, of the individual stars that comprise them collide. Despite their solid appearance, galaxies, it turns out, are made mostly of empty space.

Our own galaxy, the Milky Way, is on a course to slam into its nearest galactic neighbor, M31, the Andromeda Galaxy. When the two spirals eventually hit, in around 4.5 billion years, the end will not be cataclysmic but will result in the formation of an even larger spiral galaxy united around a single glowing core.

In our universe, objects are destined to crash together. Sometimes these collisions end with a hole in the roof or a deadly explosion; but just as often, these energetic mergings give rise to something new—a moon, a new arrangement of stars, life itself.

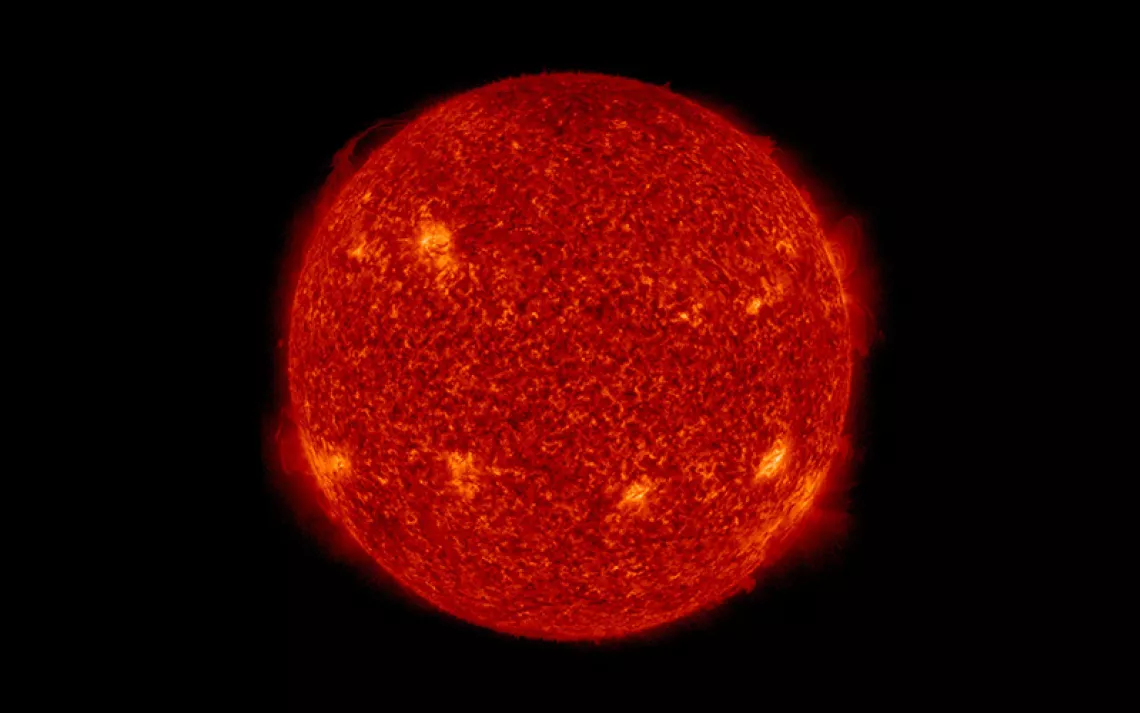

WHAT TO LOOK FOR IN NOVEMBER

November brings long nights and the Taurids meteor shower. At the shower's peak, viewers should be able to see as many as five bright streaks of light per hour, which is a fairly modest amount when compared with other showers, such as the Perseids. While the Taurids are not known for lighting up the sky, the shower is one of the longest-lasting of the year, beginning in late October and lasting until December. Though the Taurids peak on November 12, the best bet for seeing a meteor flash across the sky will be on or around November 4, during the new moon.

The meteorite activity will appear to originate from the prominent star cluster the Pleiades, or Seven Sisters, a centerpiece of the fall and winter sky. The Pleiades, known to astronomers as M45, has inspired astronomers and poets alike and is perhaps the finest deep-space object in the Northern Hemisphere to examine with a pair of binoculars. Even from light-polluted urban areas, one can make out the blue wispy veil of gases enfolding the the stars in this spectacular stellar nursery.

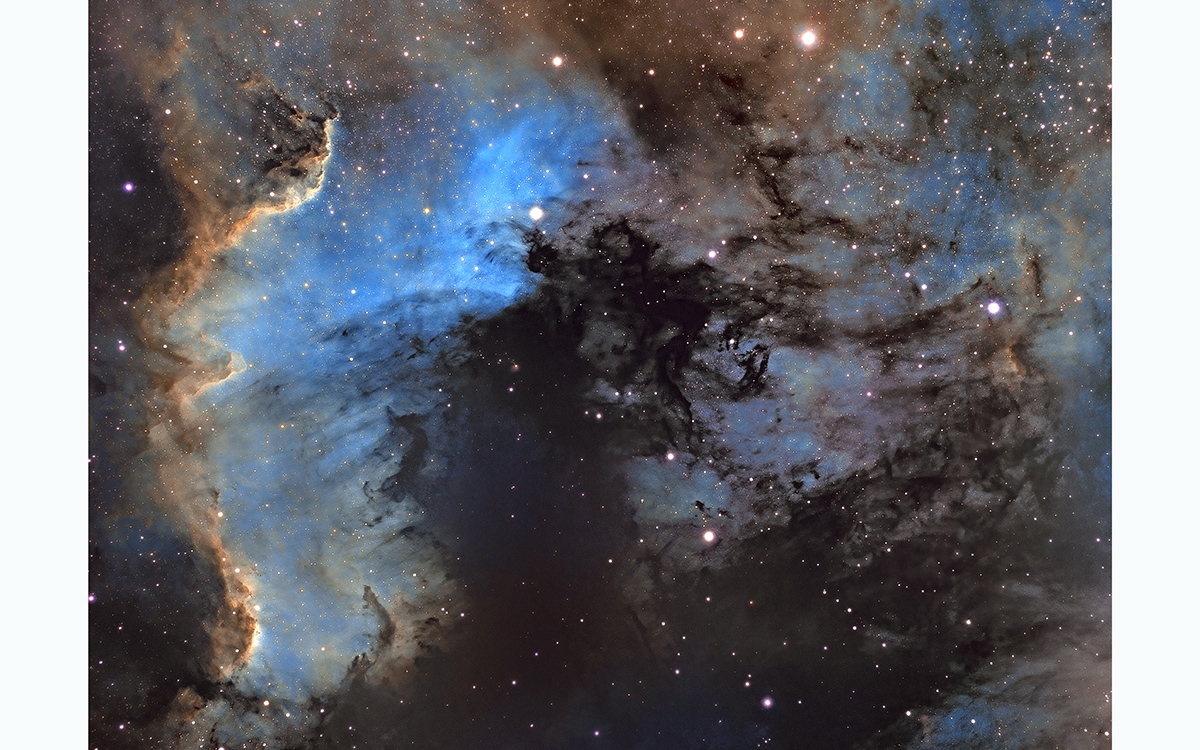

Hidden deeper in the darkness, in the constellation Cygnus, is the dimmer but equally spectacular North America Nebula. The image below is of a small fragment of the nebula and its striking feature called the Cygnus Wall. The formation is a “cosmic ridge,” a region of heavy interstellar gas and dust, in which new stars are born. In dark sky locations with a telescope or binoculars, the North America Nebula, or NGC 7000, can be seen as a faint smear. However, I took this image from my backyard, in the light-polluted environs near San Francisco, using specialized “narrowband” filters, which allow specific wavelengths of light emitted by the nebula to pass through to the camera while filtering out the rest.

The Cygnus Wall in the North America Nebula. | Photo by Jeremy Miller

Moon-watchers will want to look skyward on November 19 for a glimpse of the full Beaver Moon, named for the industrious aquatic species, which are beginning to take shelter in their lodges for the long winter ahead. (As you prepare your own winter habitations, don’t forget Ben Goldfarb’s Eager, a chronicle of the past and future of Castor canadensis, which makes great reading for the long winter nights.)

The Magazine of The Sierra Club

The Magazine of The Sierra Club