April Stargazing: Truth and Beauty

Recent images of Mars and the Milky Way have a lot to tell us

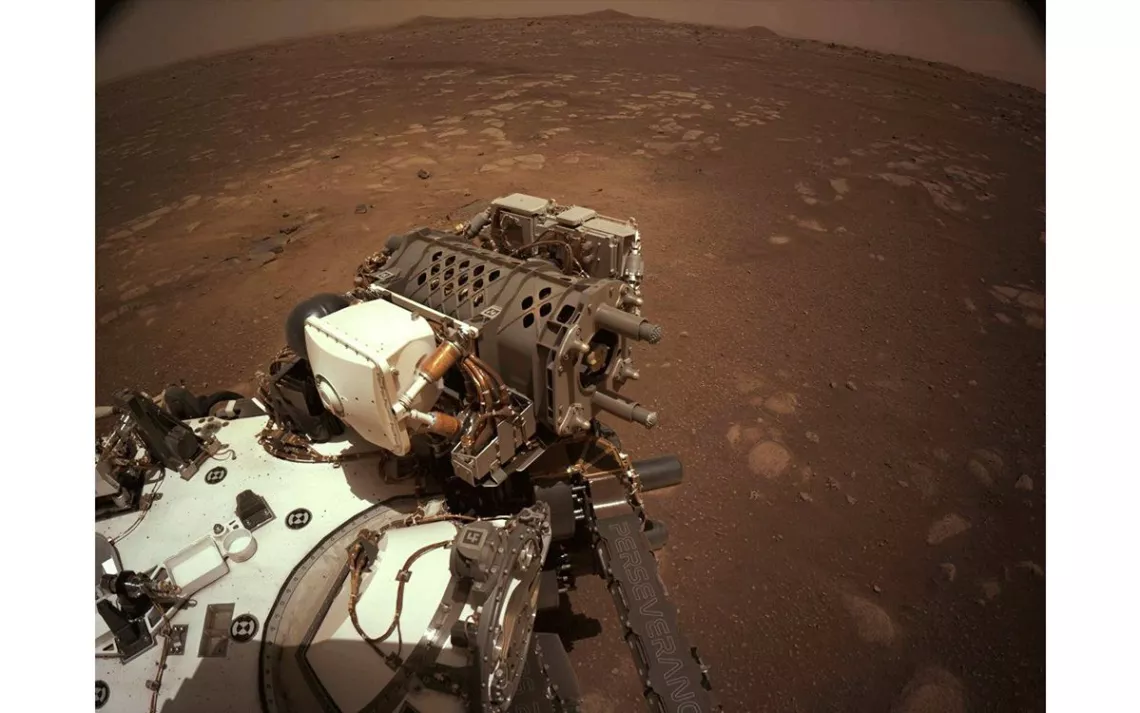

Mars rover Perseverance | Photo courtesy NASA/JPL-Caltech

Since touching down in February, the new Mars rover, Perseverance, has beamed back dozens of images. These have been captured by one of several high-definition cameras mounted to the vehicle and show the red planet in unprecedented detail. The tire tracks left in the Martian dust seem impressed into the pixels of the screen. The contours of the rocks appear crisp enough to touch. The images offer more than disparate and abstract landscapes. Taken together, they give us the most distinct impression of a foreign world that we’ve ever had.

The past few months have been an exciting time for astrophotography. Another image that has taken the astronomy world by storm reveals a much larger swath of the cosmos. Released in March by a Finnish amateur astronomer named J.P. Metsavainio, the image is a composite of some 234 individual photos and shows a massive (and massively detailed) sweep of the Milky Way galaxy. Metsavainio captured the images at his small home observatory in Oulu, Finland, and then stitched them into a panorama containing 1.7 gigapixels of data. The project is the culmination of 12 years of work and is nothing less than a revelation, showing the baroque swirls of gas flung about us in the night sky.

The Mars and Milky Way images are not merely beautiful; they represent huge strides in our ability to visualize and understand the cosmos at the smallest and largest scales. They are art and data all at once.

If we examine them as we might a great work of art, we see that their beauty is best understood in context. We can, for example, learn much from Mars’s stark, monochromatic palette of red. But its meaning increases by an order of magnitude when we contrast the ruddy monotony of the Martian surface with riotous blues and greens of our own planet. Rendered in muted blues and oranges, the gaseous wisps of Metsavaino’s mosaic resemble the delicate sun-dappled clouds in John Ruskin’s Study of Dawn. And yet, for all of its apparent comprehensiveness, the image becomes even more powerful when we consider that it only represents a small fraction of the entire Milky Way galaxy.

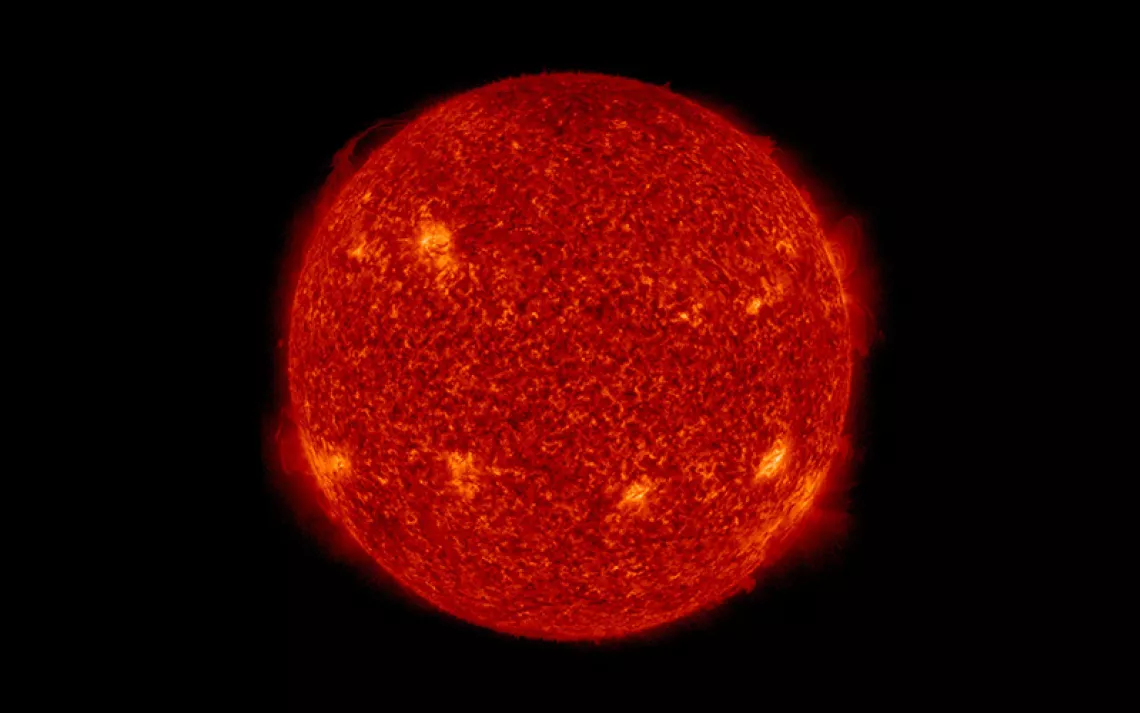

Humans are a visual species. Most of what we have learned about the universe has come through our eyes. Our eyes, however, can only detect wavelengths of light in a narrow spectrum (between 400 and 700 nanometers). Metsavainio’s images were gathered using narrowband filters that selectively allowed the very specific wavelengths of visible light emitted by the three primary gases that comprise emission nebulae—hydrogen, oxygen, and sulfur—to pass through to the camera’s sensor while blocking out all the rest.

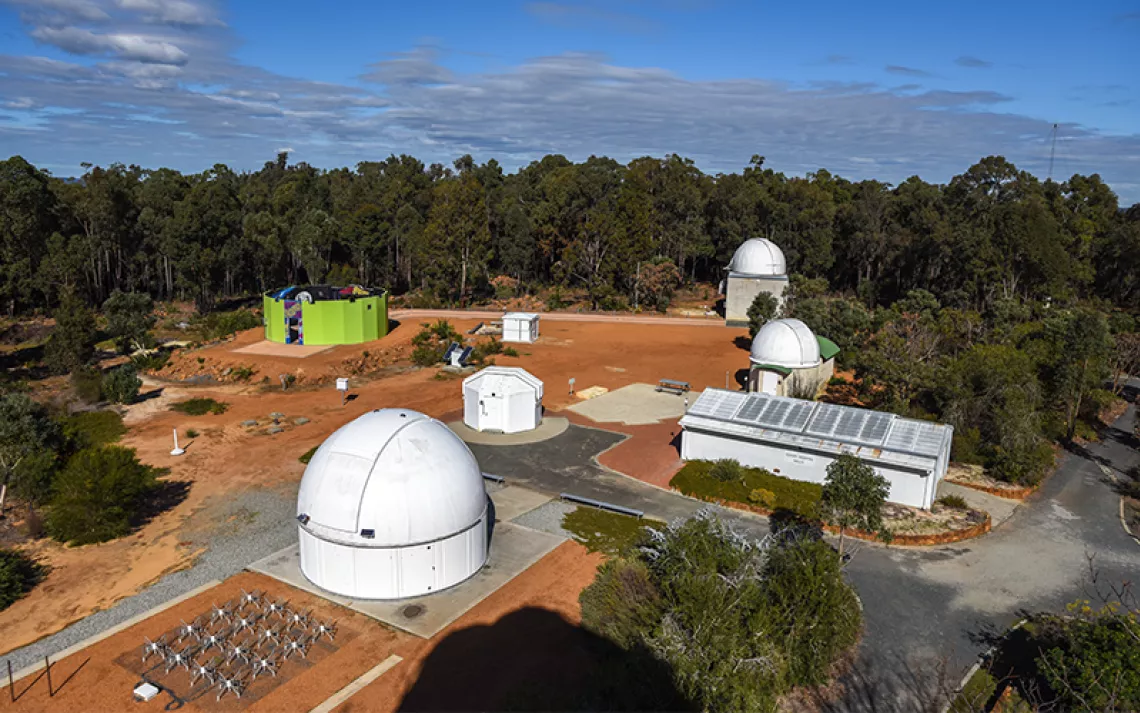

The more we delve into the universe’s secrets, the more we begin to realize that we need more than our eyes to understand its full depth. Astronomers have devised a host of special tools, from large telescopes on Earth to sophisticated cameras attached to satellites, that allow us to see across wavelengths invisible to our eyes. Across all spectra—from the radio and infrared to the ultraviolet and X-ray—we find beauty.

But what is that beauty, really—and what can it tell us about the underlying truths of the universe? Aristotle asserted that beauty is objective and related to the qualities—form, balance, composition, to name but a few—of the thing being observed. Others, such as the German philosopher Immanuel Kant, believed that beauty is a subjective experience, one that, as the old cliché goes, “lies in the eye of the beholder.” I prefer the poet John Keats’s take on the matter. In “Ode on a Grecian Urn,” Keats ponders a scene painted on an ancient vessel and ends with these famous lines: “Beauty is truth, truth beauty, — that is all / Ye know on earth, and all ye need to know.”

It is not far-fetched, I think, to say that we find beauty in images, music, objects, and ideas that tell us something about the fundamental nature of existence. In this way, Metsavainio and Perseverance’s images strike us as beautiful not merely because they are pleasing to the eye, but also because they give us new vantages on the all-encompassing but hard to perceive universe that envelops us. They are beautiful because they are true. Keats’s declaration, to me, seems as simple and profound a statement ever made on the deep but rarely explored connection between art and science.

Scientists have learned, for instance, that people tend to find symmetrical faces more attractive than non-symmetrical ones. Symmetry, it turns out, is everywhere, in structures across all scales, from objects as small as the delicate leaves of an aspen to the largest spiral galaxies. Both the aspen leaf and the distant galaxy are telling us something profound (if not yet fully understood) about the larger patterns looming in the chaos of the cosmos.

Beauty also often speaks of a connection between destruction and creation. Nowhere is this relationship more apparent than in the stars. The delicate cotton candy wisps of supernovae rendered in Metsavainio’s image, for example, tell a visual story of the violent processes that flung forth the heavy elements that compose us. Carl Sagan famously declared that we are “star stuff,” but he could just as easily—and less artfully, perhaps—have stated that we are the aftermath of dead suns.

We often find beauty inextricably hitched to feelings of melancholy. The solitary song of the nightingale, a lone peak jagging up against the sunset, Beethoven’s String Quartet Number 14—all are articulations of our isolation against the backdrop of the cosmos. For me, the recent Mars images tap into those same emotions. In the planet’s beautiful barren sweeps, we may one day find evidence of life. But one also hears the plaintive violins of Beethoven’s quartet, a faint melody underscoring our fundamental aloneness on planet Earth.

WHAT TO LOOK FOR IN APRIL

April is, as T.S. Eliot wrote, “the cruelest month, breeding / Lilacs out of the dead land, mixing / Memory and desire, stirring / Dull roots with spring rain.” For astronomers, it also marks the beginning of “Milky Way Season.” The beautiful winter constellations of Orion and Canis Major are fading into the west, and our nighttime orientation begins to return toward the core of the Milky Way. If you are an early riser and in a reasonably dark location, head outside and look overhead for the telltale white smudge of our home galaxy arcing overhead. Concentrate your viewing on the region near the cross-shaped constellation of Cygnus, which rises high enough above the eastern horizon to be seen in the hours just before dawn. The area around the bright star Deneb is notably star-filled. Through a pair of binoculars or a small telescope the area is a celestial beehive filled with hundreds of stars. For those looking for an additional challenge, set up a digital camera on a tripod (one with an adjustable shutter speed and aperture) and see if you can capture the cloudy haze of our galactic home.

April also features another significant close approach between the moon and Mars. On April 17, stargazers in Asia will be treated to a rare occultation, when the moon passes in front of the red planet. Here in North America, however, we will only see a conjunction, as the two objects will be separated by around two degrees, or the width of two little fingers held at arm’s length.

On April 26, this month’s full moon will rise, the first of two bright supermoons that will appear in 2021. Known as the Pink Moon, April’s full moon is named for a wildflower, creeping phlox, that blooms in certain parts of eastern North America this time of year. Music aficionados will also know it as the subject of this fantastic song written by the late Nick Drake.

The Magazine of The Sierra Club

The Magazine of The Sierra Club