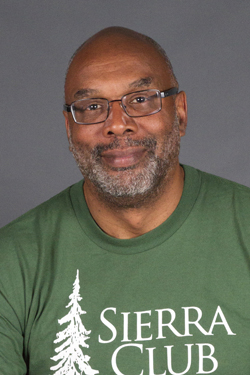

On May 16, the Sierra Club elected Aaron Mair of Schenectady, New York, as its new president. An epidemiological-spatial analyst with the New York State Department of Health, Mair brings more than three decades of environmental activism and over 25 years as a Sierra Club volunteer leader to his position as the Sierra Club's first African American president.

On May 16, the Sierra Club elected Aaron Mair of Schenectady, New York, as its new president. An epidemiological-spatial analyst with the New York State Department of Health, Mair brings more than three decades of environmental activism and over 25 years as a Sierra Club volunteer leader to his position as the Sierra Club's first African American president.

Mair became a Sierra Club member in 1999, following a decade-long battle that he led to shut down a polluting solid waste incinerator in an inner-city community in Albany, New York. His efforts ultimately led to a commitment by the state to shut down the facility and a $1.6 million settlement award to that community. Mair was also a key figure in leading the fight and securing the Sierra Club's participation in the Clean Up the Hudson campaign, which resulted in a settlement between the EPA and General Electric to dredge toxic PCB sediments from the Upper Hudson River.

Mair has held more than three dozen leadership positions within the Sierra Club's Hudson Mohawk Group and Atlantic Chapter, including chapter chair (2002-2003), chapter executive committee (2002-2004) and environmental justice chair (2009-present). He was elected to the national Sierra Club's Board of Directors in 2014.

Throughout his tenure with the Club, Mair has demonstrated an unwavering commitment to grassroots action, environmental justice, and transforming the culture of the Sierra Club to make it -- in his words -- "a more welcoming environment to all people, regardless of their race or socio-economic status."

The Planet sat down with Mair after his election as the Sierra Club's 57th president.

Planet: What first drew you to the environmental movement and environmental activism?

Mair: In 1984, when I was a young professional, my wife and I had the choice of moving to the Albany suburbs or the inner city. We chose the latter -- a high-needs community called Arbor Hill, which at the time was 80 percent black. We built a house near a school and the Tivoli Park nature reserve.

Shortly after moving in, we noticed that soot was gathering on our car, and we learned that the source was a toxics incinerator due south of our home. Our house was built in the prevailing wind pattern of the incinerator. Two of our daughters had serious upper respiratory issues, which prompted us to do research and find out the cause and then mobilize the community.

Arbor Hill had no experience in grassroots organizing; it was just families and parents in the community who cared for their children, who were going to Tivoli Park and breathing this toxic, soot-laden air. So I helped them start the Arbor Hill Neighborhood Association. And for the next ten years I organized several large civil disobedience protests that charged the then-governor of New York with environmental racism and human rights abuse for operating a failed garbage waste incinerator that negatively affected thousands of residents in Albany's inner city.

Planet: Did this lead to your involvement with the Sierra Club?

Mair: Yes. At one of our meetings of the Arbor Hill Neighborhood Association, a gentleman from the Sierra Club was present, and he invited me to make a presentation at an upcoming meeting of the local Sierra Club group. We accepted. The Sierra Club was noted for its organizing skills and effective grassroots strategies, and we followed the Club's organizing manual to a T. It proved so effective in organizing the community that we decided to enlist the Sierra Club in our effort to get the toxics incinerator shut down.

We presented our case to the Atlantic Chapter's executive committee, but unfortunately we did not win their support in helping us with our campaign in Albany. At the time, when people of color appealed to the Club, it wasn't received, and it was impossible to be unaware of the fact that we were an all-black group presenting our campaign and making our pitch for support to an all-white chapter excom. But I believe the real issue was one of resources; the Club simply wasn't sure it could take on another campaign.

Roger Gray of the chapter excom was deeply dismayed -- in fact, deeply upset. What touched me was the way Roger genuinely cared and wanted to help bring relief to our community. So I became a Sierra Club member and dedicated volunteer within the organization so that I could help change the culture of the Club from within. My goal was to take my grassroots experience and my knowledge of the EJ movement and bring the concept of environmental justice into the mainstream of the environmental movement through a big organization like the Sierra Club.

Planet: What do you see as the biggest environmental threats/challenges we face today?

Mair: Our nation is faced with a legislative climate that seeks to expand our national carbon footprint while systematically trying to dismantle the EPA. We are living in an era of the largest expanding economy while personal incomes are being depressed, creating a culture of fear and insecurity that makes protecting our immediate and global environment seem like a material luxury. Political leaders have pushed an anti-green jobs/green industry agenda and shifted the national discourse. The biggest threat right now is the political argument of climate denial funded by the 1 percent of America for its own corporate interests and profits at the expense of the environment, the people of our great nation, and the people of the globe. The Sierra Club needs to lead the charge to create and galvanize the movement that will scale up to take on this global corporate climate threat.

Planet: What role do you see the Sierra Club playing in meeting these challenges? What strengths do we bring to the table?

Mair: The Sierra Club has the foundations to build a strong, authentic movement because we're now undergoing the exercise of confronting climate change and building a movement to alter man's response -- and in so doing we can shift the world.

Back in 1992, I attended the second annual National People of Color Environmental Leadership Summit in Washington, D.C., which the Sierra Club, Greenpeace, and the Ford Foundation sponsored. The Sierra Club was coming under fire for its lack of environmental justice leadership, but I saw the Club's organizational commitment to this work.

Over the years I've worked with many, many Club leaders who are committed to making this happen. The Club sought real inclusion, starting in the early 21st century -- you can absolutely see a break in how fast and aggressively the Club moved toward inclusiveness and diversity, more than any other green group. The Club's EJ program has transformed this organization, and the Club is stronger and more powerful as a result.

Our climate work is key to this paradigm shift as we take on the biggest threats to the U.S., and the planet. Hurricane Katrina was a crystalizing moment when we all saw what needed to change -- how tepid the response was as we watched a Category 5 storm destroy a major American city where the vast majority of victims were African American. Contrast that with the reaction of the nation to Hurricane Sandy. Because Sandy hit wealthy white areas of Long Island and New Jersey -- not to mention Wall Street -- victims received immediate aid, care, and assistance. They weren't put in FEMA trailers or denied basic food assistance. They didn't have to surrender their dignity by submitting a welfare benefit card, as was the case for blacks after Katrina.

Planet: What would you like to see the Club accomplish under your presidency?

Mair: Building a strong, diverse, and inclusive environmental movement. We were able to bring a major corporate polluter, General Electric, to account with the Hudson River campaign. To achieve real progress on climate change, we need to bring together all groups. No green group by itself, no EJ group by itself, no political faction by itself, can bring about lasting changes or solutions to our climate challenges. It is only by creating a large, diverse, equitable, and inclusive environmental movement that we can bring about lasting change to save not only the planet but our species.

Planet: You are the first African American to be elected Sierra Club president. Can you say a few words about this and elaborate on its significance?

Mair: Nature is the great equalizer. Nature knows no difference between black and white, or the size of one’s wallet. The disparate responses to climate change occur at the human and political level. These are things the Sierra Club can help influence and change: the resource allocation, the response, the equal treatment of all humanity and nature. This can only come from a point of respecting diversity, when people see other people as fellow human beings and not as competitors sharing the planet.

More than 100 years ago, a president of the United States and the president of Sierra Club came together to save and preserve the last unprotected and unspoiled green spaces of the United States. That image (of two white males) came to define the environmental movement.

I now challenge our current president (who is a national leader on the environment) to meet me on the very spot in Yosemite where Theodore Roosevelt and John Muir stood, to witness the impacts of climate change on the receding glaciers and parched earth and come together not just to save a few green patches within the United States, but to save the planet.

---

Below, the Sierra Club's new board of directors. Front row, left to right: Loren Blackford, Mair, Jessica Helm, Jim Dougherty; second row: Susana Reyes, Allison Chin, Liz Walsh, Chuck Frank; third row: Steve Ma, Dean Wallraff, Margrete Strand Rangnes, Spencer Black; top row: Donna Buell, Michael Dorsey, Robin Mann.