This Women's History Month, Take It Outside

Get out and honor trailblazing women at these 10 history-rich destinations

Hallie Daggett | Photo courtesy of Siskiyou County Museum, Yreka, California

If you want to learn more about the ways in which women shaped US history—and environmental thinking—you don’t always have to read a book or watch a documentary. In honor of Women’s History Month, Sierra curated a list of a few places—many protected by the National Park Service—that honor women and their stories and let us enjoy the outdoors too.

“Women's history is American history,” Dr. Turkiya Lowe, chief historian at the NPS told Sierra. “The contributions, struggles, activism, and experiences of women—all women—define who we have become and are as a people and as US citizens. To preserve the historic and cultural spaces of women and women's history is to preserve and protect our identity and possibilities as a nation.”

In the paths that the Lowell Mill Girls walked, the house where Amelia Earhart was born, the poems that Mary Oliver wrote, the defiance that kept Rosalie Edge going, and the communities with which the Women’s Building works, may we find the inspiration to keep fighting but also to keep laughing.

Photo courtesy of Lowell National Park/NPS

Lowell National Historical Park, Lowell, Massachusetts

Lowell National Historical Park was established in 1978 to tell the story of the American industrial revolution, which is impossible to tell without the stories of the cotton textile industry and the women or “mill girls,” who were some of the country’s first factory workers. Lowell’s first factory opened in 1823 and broke with the tradition of other factories in the area by hiring women. It forged the way for young women from nearby New England farms to join the workforce. By the late 19th century, nearly two-thirds of all textile jobs in Lowell were held by women.

Working at the mills gave these women a small amount of financial independence and access to a new way of life in the city, but the work itself was hard. “The lives of these women were not governed by the seasons, the sun,” says Phil Lupsiewicz, media and communications specialist at the National Park Service. “They worked six days a week from six in the morning to seven in the evening, and their working conditions kept deteriorating.”

In 1836, the Lowell Mill Girls organized their first strike against wage cuts. Records at the National Park Service show that the strikers were feisty, claiming at an early protest that their rights could not be “trampled upon with impunity.” We could all take a lesson or two from them about working hard, to be sure, but also about receiving our just dues for that work.

Sierra suggests that after visiting the noisy looms of the Mill Museum, you walk along the canals in Lowell. The Bellegarde Boathouse on the Merrimack River has boat tours and kayak rentals during the warmer months, and the park also offers guided tours.

The Cape Cod National Seashore, Massachusetts

Mary Oliver moved to Provincetown, Massachusetts, when she was young, long before she became a National Book Award and Pulitzer Prize–winning poet. The landscapes on the outskirts of Providence appear frequently in Oliver’s poetry, as a window into the beauty, brutality, and stillness of the natural world.

During the warmer months, regular ferries run between Provincetown and Boston; it’s also possible to visit by bus. Walking along Province Lands Road is a good launching point for hiking into the marshes.

Sierra suggests getting lost for a time and paying close attention to the small things, like Oliver loved to do. The sunsets and sunrises are spectacular, but so is everything in between. “With growth into adulthood, responsibilities claimed me, so many heavy coats. I didn’t choose them, I don’t fault them, but it took time to reject them,” Oliver says. “Now in the spring I kneel, I put my face into the packets of violets, the dampness, the freshness, the sense of ever-ness.” We recommend you do the same.

Photo courtesy of Beth Parnicza/NPS

Harriet Tubman Underground Railroad National Historical Park, Maryland

This is one of the country’s newest national historical parks, established in 2014 to preserve part of the marshy, wooded landscape that Harriet Tubman, one of the most well-known conductors of the Underground Railroad, used to smuggle enslaved people to freedom. The Underground Railroad was a geographically dispersed network of people who offered aid, safe houses, and other help to escapees, and Tubman is said to have guided nearly 70 people to freedom, often risking her own life.

Tubman was born in 1822 in Dorchester County. Working in the marshlands on the shore of Maryland as a muskrat trapper and a field hand helped Tubman gain the navigational and backwoods skills that she would use to flee to Philadelphia in 1849.

According to NPS records, in 1862 Tubman was asked to help the Civil War effort in South Carolina. During the war, she assisted Union generals to recruit black troops, worked as a Union spy, and nursed hurt soldiers. In 1863, she planned and led an armed raid along the Combahee River, becoming the first woman to do so in US military history. She and her compatriots burned several plantations, destroyed Confederate supply lines, and freed more than 750 people from slavery.

Sierra suggests exploring the national historical park and then continuing to the Blackwater National Wildlife Refuge, about 12 miles south of Cambridge. The waterfowl sanctuary for birds migrating along the Atlantic Flyway provides a glimpse at the natural landscapes that Tubman grew up in.

Photo courtesy of Women's Rights National Historical Park

Women’s Rights National Historical Park, Seneca Falls, New York

The first Women’s Rights Convention took place in 1848, in the Wesleyan Chapel in Seneca Falls. It was here that the Declaration of Sentiments, a document advancing women’s rights and modeled on the Declaration of Independence, was first read.

“This was the first time a group publicly demanded the right to vote for women,” says Ranger Mary O’Neill, who works at the park. It was also the beginning of a movement that grew rapidly, setting off a chain of grassroots efforts to advance the position of women in American society.

Sierra suggests visiting the Wesleyan Chapel and the houses of two of the organizers, Elizabeth Cady Stanton and Mary Ann M’Clintock. You can also read the entire text of the Declaration of Sentiments at the Waterwall, a 100-foot-long bluestone water feature. Feel free to shed a few tears over the declaration, which, unfortunately remains as relevant as ever. Then, enjoy a scenic walk along the water, following the Ludovico Sculpture Trail.

Hawk Mountain Sanctuary, Pennsylvania

Rosalie Edge’s conservation work started in 1929, when she was 52 years old. The amateur poet and feminist is most known for creating the world’s first preserve for birds of prey, who were being hunted mercilessly at the time.

Hawk Mountain was a popular spot for sport hunters, who shot hawks migrating through the area. Edge leased 1,400 acres of the mountain and hired a warden, Maurice Broun, to take care of the property in 1934. Broun moved there with his wife and fellow bird conservationist, Irma Broun. The next year, Edge opened the area to the public as a wildlife sanctuary.

Edge was active in the women’s suffrage movement and often drew on her experiences fighting for women when struggling to gain rights for the birds of prey she cared so much about.

Sierra suggests hiking one of the many trails on Hawk Mountain, which provide stunning vista views. Don’t forget your binoculars!

If you aren’t up for a hike, just be really fierce for the rest of the month, taking a feather from Edge’s hat (not literally, she would have gotten mad about feathers on hats).

Maestrapeace murals on the San Francisco Women's Building, 18th and Valencia Streets (copyright Juana Alicia, Edythe Boone, Miranda Bergman, Susan Cervantes, Meera Desai, Yvonne Littleton, and Irene Perez).

The Women’s Building, San Francisco, California

The Women’s Building was the first women-focused community center in the United States. In 1994, seven muralists, all women, created the MaestraPeace Mural on two of the building’s walls. The mural, which is five stories high, is one of San Francisco’s biggest, unified in its theme of depicting women from different times, cultures, and even myths. “The message we are sending is that women are standing tall and holding their place,” says Tatjana Loh, development director of the organization.

Today, the building is managed according to two mandates: removing barriers that women and girls still face in the world and providing an affordable space for community groups to continue their work to improve the lives of women. The building will celebrate its 40th anniversary this year, and the mural its 25th.

La Llorona’s Sacred Waters, acrylic mural on stucco, 30' x 70', York and 24th Streets (copyright Juana Alicia).

After you visit the Women’s Building, Sierra suggests taking a short walk to Balmy Alley, where women artists have painted images of 38 women activists on a mural called Women of the Resistance. Just a five-minute walk away is La Llorona’s Sacred Waters at 24th and York. Painted by Juana Alicia, it is a stunning depiction of women fighting—in India, in Bolivia, in Mexico—for their rights, and the earth’s. Clarion Alley, at 17th and Valencia, also features murals by women artists. And if you just want to enjoy the city’s skyline and have a laid-back afternoon, head over to the Mission Dolores Park, picnic basket in tow.

Photo courtesy of Luther Bailey/NPS

Rosie the Riveter WWII Home Front National Historical Park, Richmond, California

Richmond, California, was one of many small cities and towns across America that experienced a boom during WWII, as the country industrialized for the war effort.

World War II saw 6 million women entering the workforce and "Rosie the Riveter" with her "We Can Do It" motto became a symbol of their spirit. “You have to remember that this was the time for predominantly white middle-class women to enter the workforce and shed their traditional gender roles,” says Kelli English, chief of interpretation for four national park units in the Bay Area. “But poor women and women of color had already been in the workforce for a very long time; it’s just that they now had access to these better jobs.”

These opportunities for women and minorities opened the door to equal rights and had profound impacts on the civil rights movement and women's movement during the following years.

Sierra suggests visiting the museum on Rosie Fridays, when women (most in their 90s now) who were part of the war effort come and hold court, telling their stories.

The park is walking distance from the Lucretia Edwards Shoreline Park, where you can enjoy the breeze while looking across the water to San Francisco. It also borders the San Francisco Bay Trail, a 500-mile walking and cycling path around the Bay.

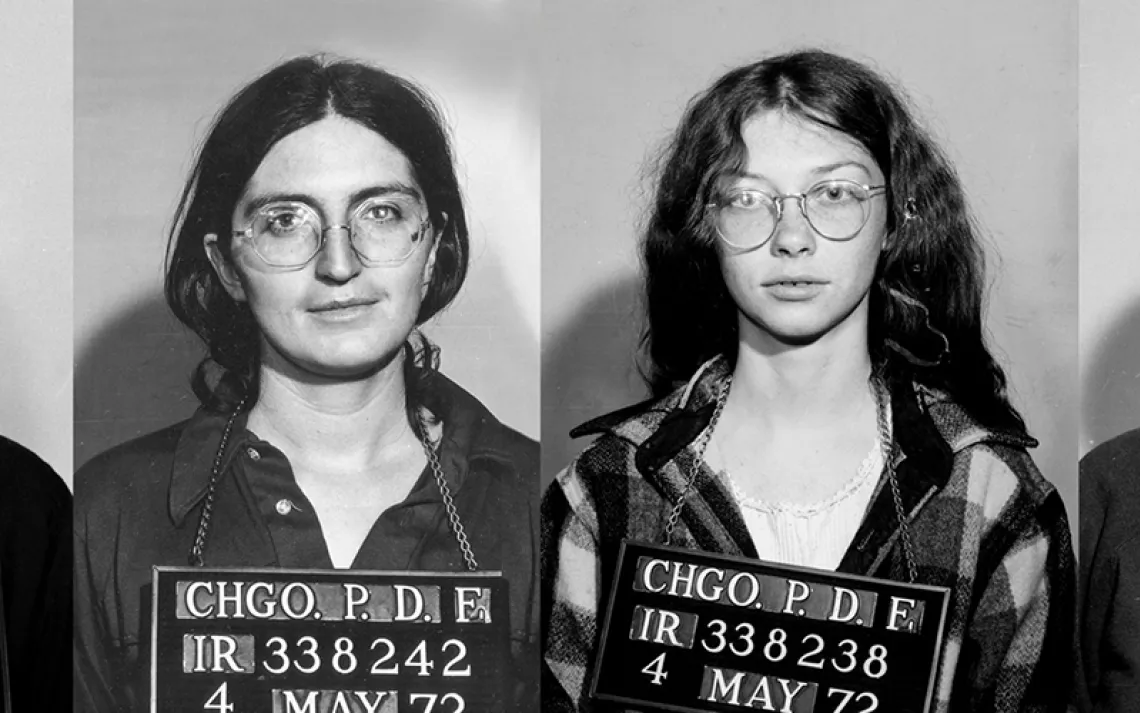

Hallie Daggett | Photo courtesy of Siskiyou County Museum, Yreka, California

The Eddy Gulch Lookout Station, Klamath National Forest, California

Hallie Daggett was the first woman fire observer in the US Forest Service. She was hired in 1913 to be a fire lookout at the remote Eddy Gulch and continued living and working at the station for 14 years, with just her dog as a companion, despite her male colleagues predicting that she would be frightened and lonely within a few days. She lived at the lookout because she loved the land and felt it was her duty to protect it. “She was a stalwart who paved her own way and paved the way for other women to do this,” says Lisa Gioia, director at the Siskiyou County Museum.

Hallie was the daughter of John Daggett, a successful miner who also served as California’s lieutenant governor. The Daggett children enjoyed exploring the trails in the Siskiyou mountains and knew how to hunt, fish, and ride.

“My interest is kept up by the feeling of doing something for my country, for the protection and conservation of these great forests is truly a pressing need. . . . To me it is work more than useful. It is a grand and glorious vacation outing, for the very lifeblood of these great foliated mountains surges through my veins,” Daggett said. “I like it. I love it! And that’s why I’m here.”

Sierra suggests visiting Eddy Gulch—solo, if possible. If you aren’t in the vicinity though, climb any peak (alone, or in the company of your dog), and look out into the wilderness. Enjoy the solitude and tip your hat to the woman “full of pluck and spirit” who did it every day for a very long time, over a century ago.

Abiquiu, New Mexico

Georgia O’Keeffe, known as the "mother of American modernism," is internationally renowned for her dramatic paintings. Born in 1887, she studied at the Art Institute of Chicago and the Art Students League in New York. Through her 20s, O’Keeffe tried to find a way of painting that expressed her ideas; her language looked radically different from what was being painted at the time.

In 1929, O’Keeffe made her first trip to New Mexico and kept coming back. The landscape, the Indigenous art, and the regional architectural style greatly inspired her.

Sierra suggests visiting the Georgia O’Keeffe home and studio and then hiking at what she called "The White Place." Known as Plaza Blanca in Spanish, it offers a stark but beautiful landscape with white cliffs and castles on view.

Alternatively, take a tour of Ghost Ranch, also made familiar by O’Keeffe. For many years, she spent her summers here, eventually buying a small parcel of land and a house on the ranch. Guided tours highlighting sites that Georgia O’Keeffe painted are also available.

Amelia Earhart Birthplace, Atchison, Kansas

Amelia Earhart was born in this home, which overlooks the Missouri River, in 1897. Earhart’s accomplishments are many, including making the first solo flight across the Atlantic in 1932 and being the first woman to make a solo round-trip of the United States. In her own words, “My ambition is to have this wonderful gift produce practical results for the future of commercial flying and for the women who may want to fly tomorrow’s planes.” In 1937, she and her navigator, Fred Noonan, disappeared over the Pacific Ocean, leaving behind one of the greatest unsolved mysteries.

Sierra suggests walking to the Atchison Riverwalk after visiting the museum. Use this time to plan your next adventure, something that catches your fancy, makes your heart sing, lights a fire in your veins. Like Earhart says, “Flying may not be all plain sailing, but the fun of it is worth the price.”

Got any favorite nature spots that are also women’s history sites? Send them to us or add them in the comments below so we can include them in a future article.

The Magazine of The Sierra Club

The Magazine of The Sierra Club