Six Lessons in Organizing From an Underground Abortion Network

In the pre–Roe v. Wade 1960s, the Janes became the doctors they wanted to see in the world

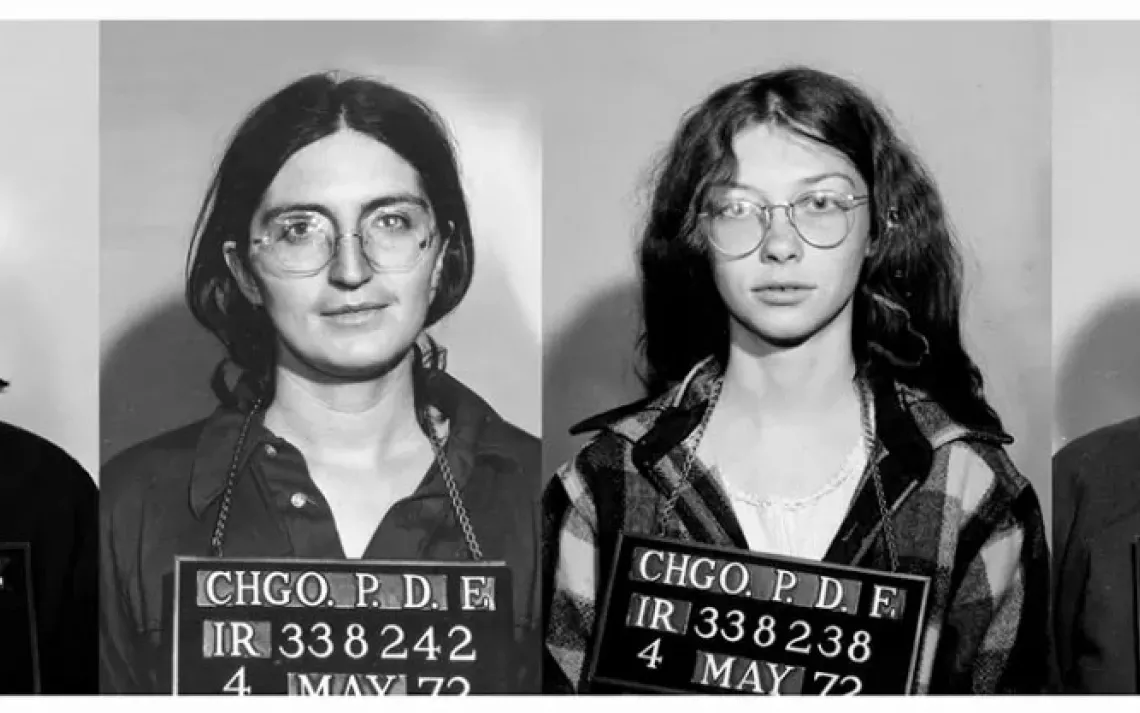

Mugshots of four Janes | Image courtesy of HBO Max

In 1964, Heather Booth, an undergraduate at the University of Chicago, traveled to the South as part of Freedom Summer. While she and other civil rights activists worked to register voters, police beat, arrested, and murdered those activists. Local and state officials—as well as members of the FBI— protected those same police from investigation. Booth never saw the law the same way again. “During that summer,” she says in the revelatory new documentary The Janes (HBO Max), “I learned I needed to stand up to illegitimate authority.”

A year later, a friend came to her for advice. His sister was pregnant, did not want to be, and was thinking of killing herself—did Booth know a way for her to get an underground abortion? Booth reached out to the medical wing of the civil rights movement, which connected her to Dr. T.R.M. Howard, a civil rights leader who had been forced to move to Chicago from Mississippi after learning he was on a Klan death list for helping to fund an investigation into the murder of Emmett Till.

Howard agreed to help. Booth made the connection, went back to civil rights and anti-war activism, and thought that was the end of that. But word got out. More people began to approach her. They were frantic—it was as though Booth had been suddenly granted access to a subterranean vein of desperation that branched out underneath normal society. Howard stopped responding to messages. Later, Booth would learn that he’d been arrested in an abortion sting.

At the time, underground abortions in Chicago—if you could find one—often involved dealing with the mob, and a tiered pricing scheme. A “Chevy” procedure cost $500 (over $4,000 in today’s dollars). A “Cadillac” cost $750 ($6,000), and a “Rolls” was $1,000 ($8,000). The astronomical prices were no guarantee of safety, or that the person who was performing your abortion had any idea what they were doing. Cook County Hospital had an entire wing dedicated to badly done abortions that had gone septic because of perforated uteruses, bladders, and intestines. The wing was always full, according to Dr. Alan Weiland, a medical student at Cook County (also interviewed in The Janes) and saw at least one death a week.

Booth decided that she needed help finding and vetting new abortion providers and advising the increasing number of people who were reaching out to her. At meetings of anti-war and civil rights activists, she began looking for women who seemed especially frustrated by the sexism that was epidemic in movement circles. (“It was always the guys. Always, forever, the guys,” recalls an interviewee named Judith Arcana. “With their macho stuff going on.”) Booth found about a dozen collaborators, and over the next four years they built an underground, feminist abortion ring together from the ground up, eventually adopting a shared persona named “Jane” to protect their anonymity.

Four of the Janes (Martha Scott, Jeanne Galatzer-Levy, Abby Pariser, Sheila Smith, and Madeline Schwenk) in 1972.

At the time, even the act of talking about how to get an abortion could get you prosecuted for conspiring to commit a felony. But Booth and other people working in the civil rights and anti-war movements had been forced to develop nearly Mafia-like skills in subterfuge just to keep doing social justice work. They already knew how to spot undercover officers, drive so that it was difficult to be followed, and communicate over phone lines that were almost certainly tapped. Until 1985, the Chicago Police Department had a “Red Squad” exclusively dedicated to surveilling progressives (and worse).

Carrying out any group project can be a challenge. Collaboratively managing an abortion ring in city full of hostile law enforcement, while trying to preserve the health and well-being of people who are, in all likelihood, reaching out to you at one of the worst points in their lives, is exponentially harder. But in the four years between when the group started and when Roe v. Wade made freedom of choice the law of the land in Chicago, the group managed to provide 11,000 abortions.

The Janes is a well-told story about a specific time, place, and collection of individuals, but watching it as a reporter who has spent nearly a decade covering grassroots movements, I kept spotting insights about organizing that felt universal. I could do with a whole activism symposium based on The Janes, but in lieu of that, here’s my own brief guide.

Potential allies might not have the same goals as you or agree with everything you do.

The Janes kept a list of which abortion providers were trustworthy and which were not, but ultimately they wound up working most closely with “Mike,” a man who had a great bedside manner and did good work, but whom several members suspected was not even a doctor. “I thought he was a blowhard,” says Jane organizer Marie Leaner. “But with heart.”

“Mike,” who manages to be one of the liveliest interviews in a consistently wild documentary, eventually admits that he was actually a union tuck-pointer who had learned several years earlier that he could make five times that doing abortions. “You would get real dirty doing tuck pointing,” he explained. “So abortions were a step up for me.”

The Janes were idealists, but Mike was in it for the money. They bargained him down to $200 per procedure in exchange for a steady volume of customers, but he refused to go lower. “I thought abortions were like mink coats,” he told one Jane. “Lots of women want them, but only some can afford one.” The discovery that “Mike” was not actually a doctor caused several Janes to leave the group—and others to train with him to learn how to perform abortions themselves. Once they could do their own procedures, they were able to drop their rate to $100 (with no one turned away due to lack of funds).

There are very few spaces where kids can’t belong.

Most of the Janes were in their late teens and early 20s when they began working together, but as the years passed, they began to have children. Allowing members—and patients—to bring children, if childcare was an issue, helped make the experience less forbidding and kept members from having to drop out of the group.

There are many ways to take on a system that you think is unjust.

The Janes were out there—even by 1960s radical standards—in the way that they deliberately chose to work on the front lines, even if that meant breaking the law. But there were other groups that operated in more of a legal gray area. Some people loaned their cars to the group, let them use their apartments for meetings or temporary clinics, or transcribed messages from the reel-to-reel tape recorder that the group used to record messages to their anonymous helpline. The University of Chicago Divinity School hosted a chapter of the national Clergy Consultation Service, which openly counseled people on how to travel to places where abortion was legal, like Mexico or England (they also often offered less legal advice off the record). Other allies worked at the state and national levels to overturn abortion bans, which ultimately helped the Janes when they failed to successfully evade the Chicago PD.

Burnout is real, and often hits the most committed the hardest.

Booth ultimately stepped back from the Janes to focus on other work, but it was not so easy for some. Jody Howard, who took a lead role after Booth left, was deeply, personally committed to abortion access. At the time, one of the justifications for not legalizing abortion was that women who really needed one, for medical or mental health reasons, could get permission from a hospital medical board. But Howard, by any empirical standard, had really needed one. She was undergoing treatment for lymphatic cancer and already parenting two young children when she discovered she was pregnant. Still, she was denied over and over again by medical boards before finally getting approval. Howard was one of the first Janes to learn how to perform abortions herself. “It was a great victory for me to challenge the medical profession,” she says in the documentary.

It was also incredibly draining. “It was a constant, endless line of suffering people,” she says. At one point, Howard left the group and signed herself into a psych ward, but it was only a temporary reprieve. Not long after, seven Janes were arrested in a police raid, and she promptly checked herself out. “I hope this doesn’t have anything to do with what I read in the paper,” Howard remembers a clerk at the ward saying as she signed her own exit paperwork.

If you can organize an underground abortion network, you can organize anything.

If you’ve spent time reporting on local government, you’ve seen this happen—people who get in the habit of organizing, whether it’s a protest or a party, find those skills to be endlessly transferable. Booth went on to have a long career as a political organizer, worked to make childcare more accessible in Chicago, started a school for grassroots organizing called the Midwest Academy, and helped start the Consumer Finance Protection Bureau. Another Jane, Abby Pariser, started a volunteer-run Planned Parenthood clinic. Sheila Avruch went on to work on maternal and child health at the Government Accountability Office. Laura Kaplan became a mover and shaker in public health advocacy. “It completely changed my life,” says Kaplan of the Janes. “I don’t think I even bothered to balance my checkbook before this. And here I was, taking responsibility for other people’s lives. It changed the way I thought about myself.”

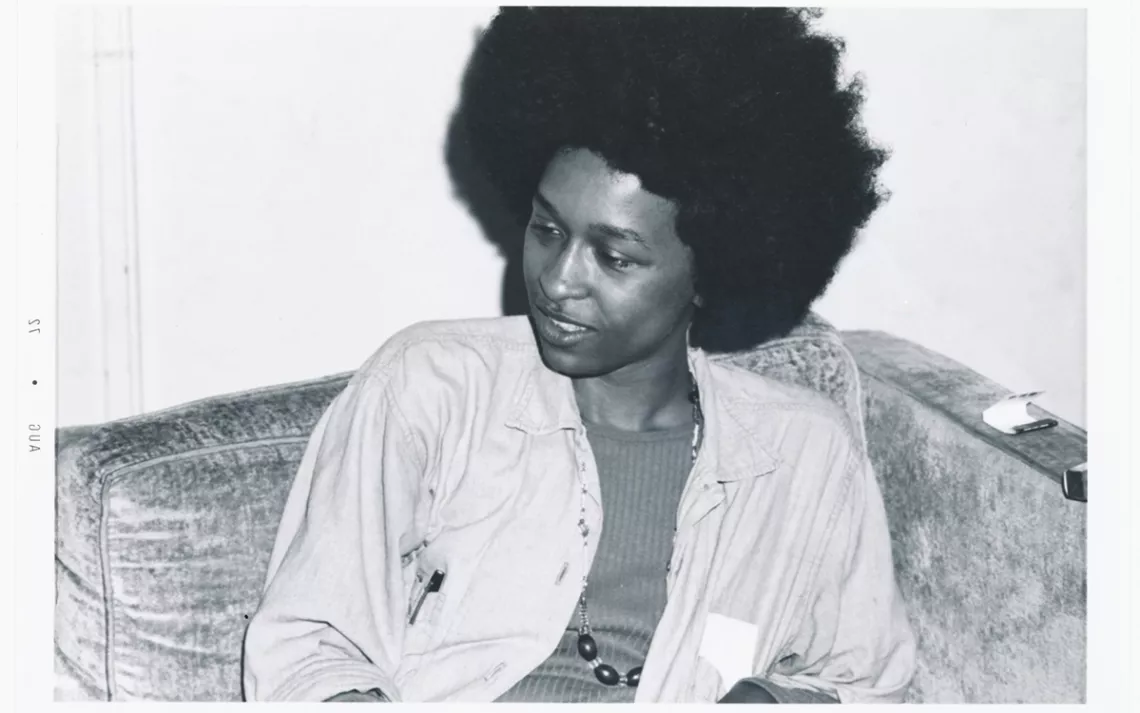

Marie Leaner during her time with the Janes

Build the world you want to live in.

It was the 1960s, and a college student in Chicago by the name of Eileen Smith was celebrating the end of the semester by getting extremely stoned. Then she heard a knock. When she opened the door, there was the girl from down the hall, with a trail of blood behind her.

Smith called the hospital. The doctor who answered the phone told her not to come in just yet. They might have seen this as an act of kindness—seeking medical attention ran the risk of police interrogation. The doctor told Smith to have the girl lie down with her legs elevated and then go buy a bag of ice for her to use as a cold compress. As Smith biked through the night, the bag of ice in her bike basket, all she could think about was how unfair it all was.

A few years later, Smith also found herself looking for an abortion—and found the Janes. At the counseling session beforehand, they served tea and snacks and described the procedure in detail. Afterward, they followed up with every patient to see how they were doing—and kept checking in for weeks after that, if patients needed it. “We wanted every woman who contacted us to feel like the hero of her own story,” says Leaner. Smith was so transformed by the experience that she became a Jane herself. “It was very different from the doctors of the day,” she says. “It was illegal, and it was the best medical experience I ever had.”

The Magazine of The Sierra Club

The Magazine of The Sierra Club