Texas Activists Are Fighting to Stop Construction on One of the Biggest LNG Terminals in the Country

South Texas communities are also resisting other LNG projects underway

Photo by Art Wager/iStock

This article originally published in Canary Media.

Juan Mancias and I are sitting in his Dodge Ram pickup truck when a sharp jolt shakes him in his seat. The truck is stuck in deep muck on an unpaved road in southeastern Texas, and a rugged Jeep is trying to pull us out. With another forceful yank, the vehicle frees the Dodge. From my seat behind Mancias, I find my belongings flung on the floor.

Mancias is chair of the Carrizo/Comecrudo Tribe of Texas, an Indigenous people whose ancestral lands span the delta region where the 1,900-mile Rio Grande meets the Gulf of Mexico. On a drizzly day in December, we’ve come out to survey the patchwork of parcels the tribe recently purchased near the Bahia Grande tidal basin. These acres of sandy soil and hardy grass run along the proposed route of the Rio Bravo Pipeline—a 137-mile conduit that would funnel shale gas from East and West Texas to a major new fossil fuel project on the Gulf Coast.

Mancias was navigating the neglected county roads near the properties when we became ensnared in mud. By buying up acres of land, the tribe hopes to obstruct the pipeline’s development here and choke off some of the supply to the Rio Grande Liquefied Natural Gas export terminal. The facility, now in the early stages of construction, will super-cool and liquefy gas to be shipped overseas.

“They’re trying to justify and redefine everything as ‘critical infrastructure,’” Mancias says of the fossil fuel projects. “But the real ‘critical infrastructure’ is the air, the water, and the land,” he adds while we await the rescue Jeep. We pass the time by spotting hawks and blue herons and swatting at big mosquitoes that snuck in through the open windows.

Deep mud puddles abound on the back roads between Brownsville and Port Isabel, Texas. | Photo by Maria Gallucci/Canary Media

If completed as planned, NextDecade’s Rio Grande LNG export terminal will be one of the largest projects of its kind in the country—accelerating the boom in US LNG exports that’s taken hold over the last decade. The project’s first and largest phase is expected to cost around $18.4 billion to build.

The new terminal will also be the first large oil and gas development on this largely unspoiled coastline near the United States–Mexico border. Over the last century, as companies built polluting petrochemical plants atop wetlands in much of Texas and Louisiana, the southeastern tip of Texas has remained a haven for birds, marine life, and the thousands of people who live and work on the water.

Rio Grande LNG is set to span nearly 1,000 acres along the Brownsville Ship Channel and, at full scale, could produce 27 million metric tons of LNG per year. That’s enough fuel to meet the heating and cooling needs of nearly 34 million US households annually—except that the LNG is destined for other countries. Next door, on a 625-acre stretch of black mangrove, the developer Glenfarne Group is trying to build another export terminal, called Texas LNG.

Illustration by Binh Nguyen/Canary Media

The giant fossil fuel developments have garnered support from Cameron County officials and Brownsville business leaders, who welcome the developers’ promises to provide hundreds of permanent jobs and generate hundreds of millions of dollars in local economic benefits. The wider Rio Grande Valley, which is home to nearly 1.4 million people, has some of the nation’s highest rates of poverty and unemployment.

Yet many residents here say they fear the new LNG infrastructure will ultimately do more harm than good for communities and the nature-based economy. Over the last decade, a broad coalition of city council members, Indigenous leaders, environmentalists, and tourism operators has emerged to try to stop these projects through legal challenges and public protests.

Opponents worry that pollution-belching plants and enormous LNG ships will keep visitors away from the region’s wildlife sanctuaries, infinitely long beaches, and emerald waters filled with shrimp, fish, and back-flipping dolphins. They’re concerned the facilities will exacerbate the climate crisis and jeopardize people’s health and safety— worsening injustices in an area where the vast majority of people identify as Hispanic or Latino.

Residents need only drive northeast along the Gulf Coast to see their fears become a reality, says Bekah Hinojosa, an organizer with the South Texas Environmental Justice Network.

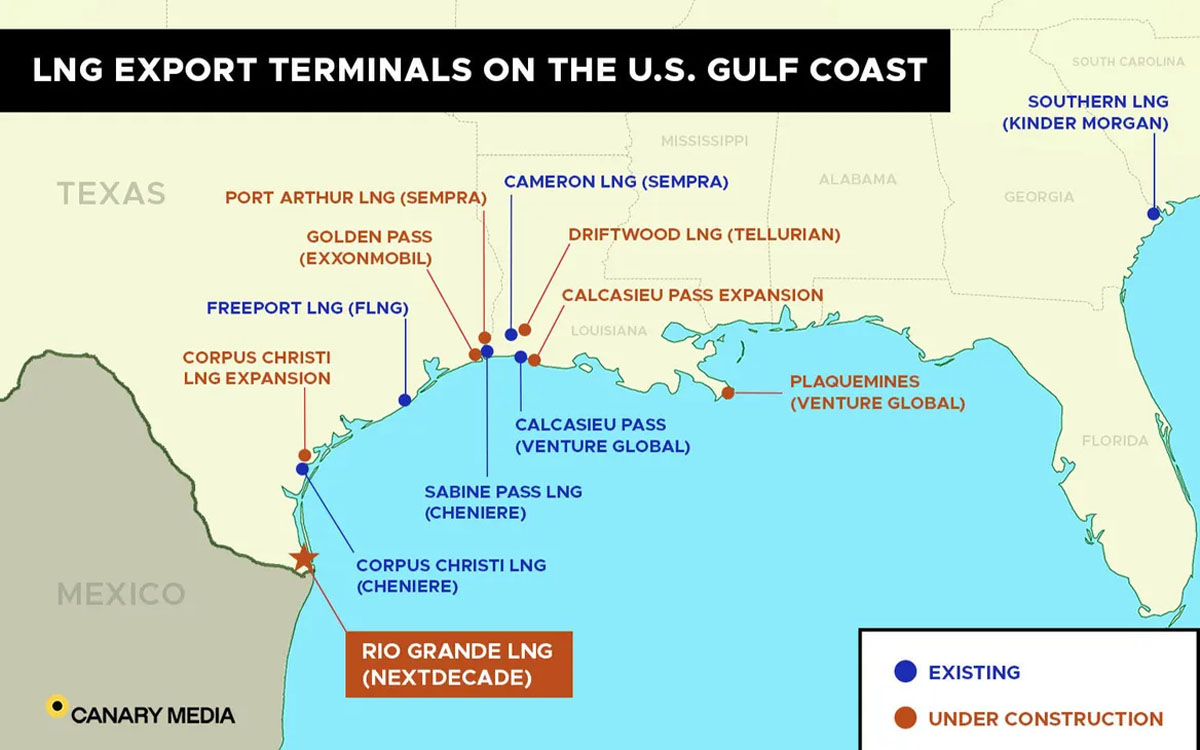

Massive LNG export terminals are already flaring gas and spewing significant levels of toxic air emissions near the cities of Corpus Christi and Freeport in Texas, and in the community of Hackberry and Sabine and Cameron Parishes in Louisiana. One of those facilities, the Freeport LNG plant, partially exploded in 2022, sending a fireball 450 feet into the air. Workers were injured, but the blast revealed systemic failures at the country’s second-largest export terminal.

Bekah Hinojosa has been fighting oil and gas projects in the Rio Grande Valley and beyond for nearly a decade. | Photo by Verónica Gabriela Cárdenas for Canary Media

“We don’t have exploding refineries here, and we want to keep it that way,” Hinojosa says from her office in downtown Brownsville, on a stretch of semi-vacant storefronts just blocks from the border crossing. “What we want to see instead is support for renewable energy that is led by the community.”

Hinojosa’s family has lived in the Rio Grande Valley for generations. In her previous job at the Sierra Club, she helped mount a yearslong effort to block a third proposed export terminal, called Annova LNG, through legal actions and by pressuring international banks and potential European customers not to support the project. In 2021, the developer scrapped its plans after failing to secure long-term offtake contracts.

Now, LNG opponents are working to block the two other export terminals slated for the area as well as the gas pipelines that will feed them, hoping to stop the construction trucks in their tracks before the projects advance further. Most recently, on February 27, members of the Carrizo/Comecrudo Tribe and environmental groups visited New York City to protest outside the headquarters of Global Infrastructure Partners, the largest investor in Rio Grande LNG. Activists brought wetland samples from the Texas construction site and a letter demanding that the private equity firm withdraw its support for the project.

“Our communities don’t want to be sacrificed,” Hinojosa tells me. “We don’t want these projects here or anywhere else.”

*

The fight to determine the future of South Texas is escalating just as the broader debate over LNG exports heats up in Washington, DC, and nationwide.

In late January, the Biden administration said it was pausing all pending decisions on new LNG export approvals. The US Department of Energy (DOE) will take a “hard look” at how those fossil fuel shipments impact climate change, domestic energy prices, and America’s energy security—for the first time since the LNG export boom began eight years ago.

The announcement was widely celebrated by climate activists and Democratic lawmakers, who have accused the DOE and the Federal Energy Regulatory Commission (FERC) of “rubber-stamping” LNG projects with minimal scrutiny. The decision also garnered support from a group of manufacturers, chemical companies, and consumer advocates, who say that exporting America’s gas supply could make energy markets more volatile at home.

Meanwhile, fossil fuel lobbyists and pro-LNG lawmakers from both political parties have blasted the Biden administration’s move as a “reckless” political ploy, one that undermines US energy security and hurts European allies trying to wean themselves off Russian gas. The Republican-controlled House recently passed a bill to overturn the LNG export pause; while unlikely to pass in the Senate, the bill earned praise from the head of Texas’s oil and gas regulatory commission.

The temporary pause is expected to last for months, and it will primarily affect the six major proposed LNG export terminals waiting to secure approvals from FERC, DOE, or both. But the Biden administration’s decision doesn’t impact any of the nation’s eight active facilities—which together made the United States the world’s largest LNG exporter last year. Since February 2016, when the lower 48 states first began exporting LNG, the amount of US fossil gas shipped overseas has risen from near zero to 88.9 million metric tons in 2023.

Illustration by Binh Nguyen/Canary Media

Nor does the pause affect the seven export terminals currently under construction—such as Rio Grande LNG—or any additional projects that have received the necessary federal approvals to start building, including Texas LNG.

Christa Mancias-Zapata, the executive director of the Carrizo/Comecrudo Tribe and Juan Mancias’s daughter, said that while she welcomes Biden’s decision, it represents only a “little win” for South Texas communities and the tribe itself. The Rio Grande LNG and Texas LNG terminals and two gas pipelines encompass land that is sacred to the Carrizo/Comecrudo people. The site of the Texas LNG project, for example, contains the remnants of an ancient burial site called Garcia Pasture, which the tribe is no longer permitted to access.

“Unfortunately, for what I’m protecting at the end of the Gulf in Brownsville,” the pause doesn’t stop development, the younger Mancias said during a Washington, DC, press event held in early February. “The area we are protecting is still being destroyed.”

But anti-LNG groups say they don’t think it’s inevitable that all these projects will be completed. Environmentalists and community leaders are working on multiple fronts to hold back the tide of fossil fuels, including an ongoing legal challenge led by the Sierra Club, the Carrizo/Comecrudo, and the South Texas Environmental Justice Network.

When FERC approved the construction of the Rio Grande LNG Terminal and the Rio Bravo Pipeline in November 2019, the Sierra Club and other parties took swift legal action, arguing that neither the developers nor FERC properly assessed the projects’ potential impacts on climate change or air pollution within environmental-justice communities. In August 2021, the US Court of Appeals for the DC Circuit sided with opponents, finding FERC’s analyses to be “deficient.” The court issued a “remand order” requiring FERC to reassess those issues. The commission did, and in April 2023, it reapproved the gas projects.

Now, environmental groups are fighting the remand order in the DC Circuit Court. Late last year, they filed a “motion to stay” with FERC hoping to stop construction work while the litigation is ongoing, but FERC denied the petition. On February 7, the Sierra Club pressed the DC Circuit Court to issue a stay order instead.

Juan Mancias, tribal chair of the Carrizo/Comecrudo Tribe of Texas, points to the tidal ecosystem in Boca Chica, near where SpaceX built a controversial rocket factory. | Photo by Maria Gallucci/Canary Media

Meanwhile, the Carrizo/Comecrudo are continuing their strategy of buying acres of land along the Rio Bravo Pipeline route to try to stymie development. During my December visit, Juan Mancias acknowledged the challenges facing the tribe. The developer, Enbridge Inc., could claim “eminent domain” to force its conduit through and, as Mancias puts it, occupy the Carrizo/Comecrudo’s ancestral lands once again.

“We want to bring back the native plants, for one thing,” he says when I ask him what future he sees for the ranchland around us. The tribe also plans to use about half of the 23 acres it’s purchased so far to set up a school to preserve the tribe’s lifeways. “We’re trying to protect our language as well, just as we’re trying to protect our land,” the tribal chair adds.

*

The day after my muddy excursion with Mancias, I decide to join a four-hour boat tour in the blue-green waters off of Texas—I want to take in the coastal beauty and to see how far construction on the Rio Grande LNG export terminal has progressed.

To get there, I drive east from Brownsville to Port Isabel, along Highway 48. On one side of the two-lane road is a sprawling tidal basin filled with seagrasses, redhead ducks, and redfish. On the other are construction cranes, trucks, and acres of dirt. At the water’s edge, the road rises into a 2.4-mile causeway connecting the mainland to Padre Island.

The barrier island was formed 2,000 years ago out of soil that washed into the Rio Grande and flowed down to the Gulf of Mexico. Much of the 113-mile-long strip of land is preserved as a national seashore and wildlife refuge. But the southernmost spear, called South Padre Island, is a tourist destination for millions of wintering Northerners, spring-breakers, and other visitors every year.

Seeking to preserve all of this, the seaside cities of Port Isabel, South Padre Island, Laguna Vista, and Long Island Village have all passed resolutions opposing the buildout of planned LNG export terminals.

“The natural environment is what sustains our economy,” says Jared Hockema, the city manager of Port Isabel, which is home to 5,000 people and a popular historic lighthouse. “In many cases, the way that we reap economic benefits from the environment is not by doing something, but by doing nothing—by leaving it alone.”

Construction on the Rio Grande LNG export terminal is visible from a tour boat cruising toward the Port of Brownsville. | Photo by Verónica Gabriela Cárdenas for Canary Media

At the dock, I follow a group of out-of-towners onto a tour boat called the Thunderbird. Soon we’re cruising in the hypersaline Laguna Madre bay, headed toward the Port of Brownsville. Bottlenose dolphins race alongside our vessel, bursting suddenly from the wake as we veer west to enter the Brownsville Ship Channel.

For a while, we’re surrounded only by choppy waters and thin sandy cliffs topped with stubby palms. In the distance, we can see the outlines of SpaceX’s Spaceport, a controversial rocket factory and launchpad on the coastal prairies of Boca Chica. Suddenly, on the channel’s northern bank, construction equipment comes into view. The orange claws of excavators move nearly in unison as they scoop dirt and clear the way for the export terminal.

Houston-based NextDecade broke ground on the first phase of its Rio Grande LNG project on October 3. Events that day featured ceremonial golden shovels and flutes of Champagne, with county and port officials in attendance. Esteban Guerra, chairman of the Brownsville Navigation District, which leased the land to the developer, praised the project for “strengthening the reputation of South Texas as a formidable place of business.”

To start, NextDecade plans to build three liquefaction “trains,” which together will be capable of liquefying enough fossil gas to produce 17.6 million metric tons of LNG per year. Where today we see cranes and trucks could soon become a vast and towering complex of gas turbines, generators, thermal oxidizers, and ground-flare systems, which are expected to start producing LNG in mid-2027.

A brown pelican floats in the waters near the Brownsville Ship Channel. | Photo by Verónica Gabriela Cárdenas for Canary Media

The shale gas will arrive here from the Permian and Eagle Ford basins via the Rio Bravo Pipeline and the Valley Crossing Pipeline, both of which are owned by Enbridge Inc. The second pipeline currently exports gas to Mexico, though Enbridge is seeking to expand the conduit’s carrying capacity and length. The Rio Bravo Pipeline—the one the Carrizo/Comecrudo Tribe is trying to thwart—is still going through regulatory proceedings involving four proposed route adjustments. Construction is slated to begin next year.

The piped-in gas will be liquefied through an energy-intensive process that cools the fossil fuel to -260 degrees Fahrenheit. In this form, companies can load greater volumes of the fuel onto big tankers, many of which will likely head to Europe and Asia. Once the Rio Grande LNG export terminal is operating, about four tankers stretching nearly 1,000 feet long could initially navigate the ship channel every week.

The terminal will produce “a lower-carbon-intensive LNG, supporting the transition to a lower-carbon economy and helping meet energy demand around the world,” a spokesperson for NextDecade said by email.

The company claims it will source gas supplies from producers that are taking steps to reduce leaks of planet-warming methane and eliminate harmful flaring and other environmental measures. NextDecade has pledged to use “net-zero” electricity to power its own operations near Brownsville. The company also plans to install systems that capture and store up to 5 million metric tons per year of carbon dioxide emissions at the site—something that hasn’t been done before at any gas export facility.

NextDecade didn’t provide any details about where the net-zero power will come from or directly address questions about the cost and construction timeline of the carbon-capture system, or where the company will store the captured CO2. Instead, the spokesperson pointed to NextDecade’s most recent corporate presentation.

Matt Schatzman, the company’s chairman and CEO, has said that he hopes the project will be one “that exceeds expectations and leaves a lasting legacy on this community.”

*

Noe Lopez says he worries that legacy will ultimately be a negative one, not just for the natural environment but also for the ecotourism that depends on it.

I meet Lopez after my boat tour through the Brownsville Ship Channel. Driving back onto the mainland from South Padre Island, I stop by a bright-yellow waterfront shop beside the causeway. Lopez is a manager and co-owner of Dolphin Docks, a company he’s run for nearly three decades in Port Isabel. He greets me with a bright smile, an unlit cigarette dangling from his mouth, then invites me to talk inside a boat that’s docked in the back.

In the peak summer season, he explains, his crew can take up to 300 people a day out on five or so dolphin-watching and fishing tours. Once the lumbering LNG vessels start traversing the ship channel, recreational boats are expected to experience frequent delays, which Lopez worries will limit the number of tours Dolphin Docks and other companies can offer.

Noe Lopez stands aboard one of his tour boats at Dolphin Docks in Port Isabel, Texas. | Photo by Maria Gallucci/Canary Media

“So many months out of the year, that’s how people survive around here,” he explains. “When the [LNG] ships come in, will we have to shut down then?” If that happens, “It’s gonna be bad,” he says with a dark laugh.

Another legacy of the LNG developments will be their impact on the planet’s climate.

When burned, fossil gas emits about half as much carbon dioxide as coal. However, gas is primarily composed of methane—a potent greenhouse gas whose near-term warming power is many times that of CO2. Methane is prone to leak throughout its complex supply chain, from the gas well to the power plant that burns it, further increasing the fuel’s life-cycle emissions.

The net climate impact of exporting LNG ultimately depends on whether the fuel is displacing cleaner renewables or dirtier coal in the importing countries—and on the types of measures companies take to prevent methane leaks at every step, Arvind Ravikumar, an associate professor at the University of Texas at Austin, recently wrote in MIT Tech Review.

Even so, scientists are clear that over the long term, gas production is “inconsistent” with the Paris Agreement’s goal of limiting global warming to 1.5 degrees Celsius. In South Texas, the two LNG export terminals and two gas pipelines could together generate about as much greenhouse gas emissions as driving about 40.4 million cars per year, according to the Sierra Club.

Each facility also represents a major potential source of air pollution; together, their cumulative impacts on air quality would be significant. The Rio Grande LNG terminal alone is expected to spew thousands of tons per year of carbon monoxide and nitrogen oxides, as well as hundreds of tons of volatile organic compounds. The chemicals can cause neurological effects like headaches and dizziness, damage people’s lungs and trigger asthma attacks, and contribute to soot and smog.

Emma Guevara, the Sierra Club’s Brownsville organizer, says these public-health threats are even more concerning when considering that many people in the Rio Grande Valley lack access to affordable, high-quality health care. In the four-county region, between 24 and 33 percent of residents under 65 lack health insurance, compared to 9.8 percent nationwide.

“We’re already one of the most underserved areas in the entire United States,” she says, adding a direct plea to fossil fuel companies: “Please don’t come into our already very marginalized community and try to play in this place.”

Emma Guevara is the Sierra Club's organizer in Brownsville, Texas. | Photo by Verónica Gabriela Cárdenas for Canary Media

NextDecade said that “the safety of the communities and environment where we operate are at the heart of all we do.” The Rio Grande LNG export terminal “is not expected to have an adverse impact on offsite beaches or tourist areas,” the spokesperson said by email, while noting that NextDecade has worked to involve community members by hosting open houses and over a dozen safety demonstrations at local schools over the last year.

Back on the palm-tree-lined streets of downtown Brownsville, when I meet Bekah Hinojosa at her shared office space, she shows me a stack of photocopied forms with handwritten entries in English and Spanish. The organizer has been gathering and translating public comments about the Rio Bravo Pipeline to submit to FERC.

On the forms, residents write their concerns that the pipeline and LNG terminal could drain water supplies in a region prone to drought. They worry about dirty air. They wonder about the projects’ proximity to SpaceX’s launchpad—recent launch attempts shook buildings as far as several towns away and flung debris onto the surrounding area. (NextDecade said the company has developed safety protocols should a launch or other event pose a risk to the facility.)

Along with collecting comments, Hinojosa says she and fellow organizers are meeting regularly with financial institutions, including the Washington State Investment Board, or protesting outside their headquarters—like the most recent action in New York City—to try to dissuade would-be financiers and insurance companies from supporting the LNG developments, a tactic that proved effective with the now-canceled Annova LNG terminal.

“There’s no secret recipe to stop an LNG facility,” Hinojosa says.

Activists will certainly need every strategy they can muster. Every day, it seems, another yellow dump truck or gnawing excavator appears on the banks of the Brownsville Ship Channel. In a state dominated by the oil and gas industry, on a coast where LNG terminals already stretch across large swaths of swampland—and in a country where regulators are reluctant to scrutinize fossil fuel projects—the LNG industry can feel like a juggernaut, a fast-moving train without any brakes.

Faced with this reality, Guevara, the Sierra Club organizer, is matter-of-fact.

“We get a lot of questions like, ‘You don’t really think you’re going to stop this, do you?’” she says. “We’ve done this before. I don’t see why we can’t do it again.”

This article has been updated since publication.

The Magazine of The Sierra Club

The Magazine of The Sierra Club