Meet the World's Most Bugged-Out Military Photographer

Check out Pablo Piedra's insect macrophotography

Pablo Piedra is proof that there’s no such thing as a retired artist. After 22 years in the military, most of which were spent as a photojournalist, he left Virginia for Costa Rica in 2019 and found himself bored and disillusioned. “I was in a creative vacuum and getting very grumpy,” Piedra recalls. He found inspiration in the work of Costa Rican insect macrophotographers like Marco Retana, and—taking stock of the fact he lived in the middle of the rainforest in one of the most biodiverse countries in the world—he decided to go find some bugs.

With help from his wife, Daniela, their seven-year-old son, Jaden, and the family dogs, Piedra started looking for native insect carcasses during morning hikes. “We’d find two or three new ones every time,” says Piedra, who also started studying his pool and terrace for deceased insects. Soon, he was scaling down the equipment in his home studio and adapting his workspace to his tiny new subjects. “I started making homemade diffusers and reflectors out of everyday things like cans and bottles,” he says. “It consumed my time in a positive way. I had dabbled in macro before, but really doing it took so much time and patience and technical skill and relearning, I fell in love with it—and with insects.”

Piedra first picked up a camera shortly after joining the Army Reserve at age 17. “We lived in Nebraska, and I was bored and didn’t want to work in the bean fields,” he says with a laugh. After high school, Piedra went active duty, got stationed in Heidelberg, Germany, and soon became his unit’s volunteer photographer. His images were good enough that army public relations pros often hounded him for them, and eventually, a sergeant major pulled him aside and said, “You know the army has professional photographers, right?”

“He introduced me to the field of combat photography and helped me with the paperwork, and within six months I was an army combat documentation and production specialist, or COMCAN—we’re the guys on the ground taking photos where civilians can’t go,” Piedra says.

Piedra traveled to more than 50 countries, on both conflict and humanitarian missions. He documented Puerto Rico in the wake of Hurricane Maria, did missions in Southeast Asia, and logged days and weeks in conflict zones in places like Burma, Ukraine, and the deserts of Kuwait. Every chance he got, he was off researching and shooting more nature- and travel-oriented imagery. “When others were hitting the gym or the bar, I’d get permission from whomever I was with to use my little bits of free time capturing parts of the world I figured I’d never get a chance to go back to.”

The son of a National Geographic cartographer and hobby photographer, Piedra may have come by this drive honestly. “I remember sitting for hours as a kid, watching my dad’s slideshows,” he recalls. “I was really struck by the power of being able to capture an image in nature and then years later, show the world to someone else the way I see it and get an emotional reaction from that.”

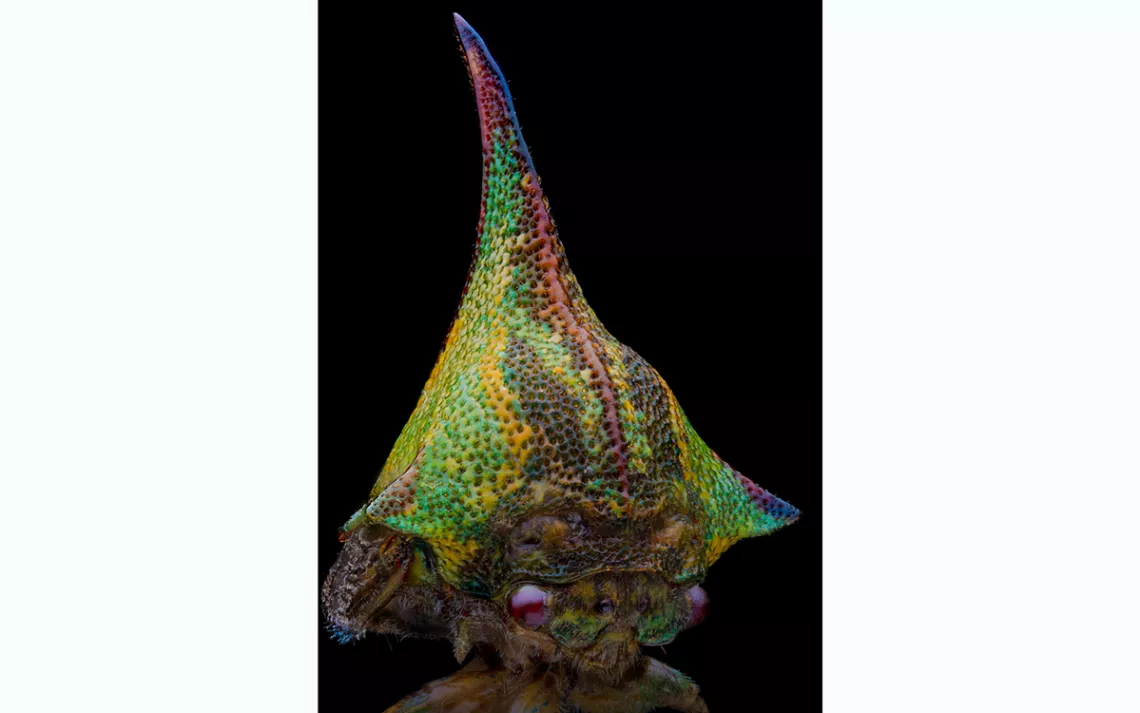

Well aware that most people’s emotional reactions to flies and roaches are, well, along the lines of ewwwwww, Piedra is all about providing that closer, completely different perspective. “Insects are the largest genome of animal life on this planet; it’s a hidden world that wows when we really look at it,” he says. “Even when I find a new insect, I don’t know what I’m actually going to see until after I spend hours cleaning and prepping it and finally get it in front of the camera." (This entails using a little blower and a size #00 pin/needle to pick the grains of dirt or hairs off the creature.) "Then I zoom, and it’s like Wow! Look at that eye! Or mouth!’”

That’s when Piedra decides what to emphasize about the insect, and thus how to style the photo. Each final image is composed of tens, sometimes hundreds of individual stacked frames. An average photo takes around six hours, but getting the light just right can require days. Since his subjects are all found dead, the decaying process creates its own race against time.

While he doesn’t have any formal entomology education, Piedra labors to correctly identify and research every insect he shoots—and thus to artistically emphasize whatever makes it special. “Bugs are very apt at whatever their evolutionary role is—their purpose is always really clear and fascinating,” says Piedra, who now liaises with entomology pros and donates images to universities. “I’ve photographed maybe 17 different types of wasps, and each has a different mandible for different things.” While his pursuit is purely artistic, the further he progresses in his new retirement vocation, the more he can tell, “Oh that moth or beetle is in that family or genre.” Finding a bug he hasn’t found before, he says, is “almost like a jigsaw puzzle—I still have photos I haven’t published because I don’t know what they are.”

Using experts, books, apps, and the internet, Piedra triangulates his way to answers. “It’s a very nerdy but very cool world,” he says with a laugh. “When you finally find the right obscure website and share it, it’s like you cracked the case!”

The most rewarding moments for Piedra occur when someone takes in a photo and says, “I used to be scared of bugs, but now I see them in a different way.” He adds, “Just like I used to approach my soldiers in the army, it’s about showing somebody mundane things in a special way, about taking them on your emotional adventure.” After all, “it’s the beauty that’s all around us that we don’t see, because we don’t take the time to see it. When we take the time to look at things from a different perspective, we find wonder all around us.”

Piedra's images appear in Sierra's Spring 2022 issue's "Aliens Among Us" feature. One of his bugs also stars on the cover of our Spring issue's Spanish-language edition.

The Magazine of The Sierra Club

The Magazine of The Sierra Club