Inside the Rise of Bee Lawns

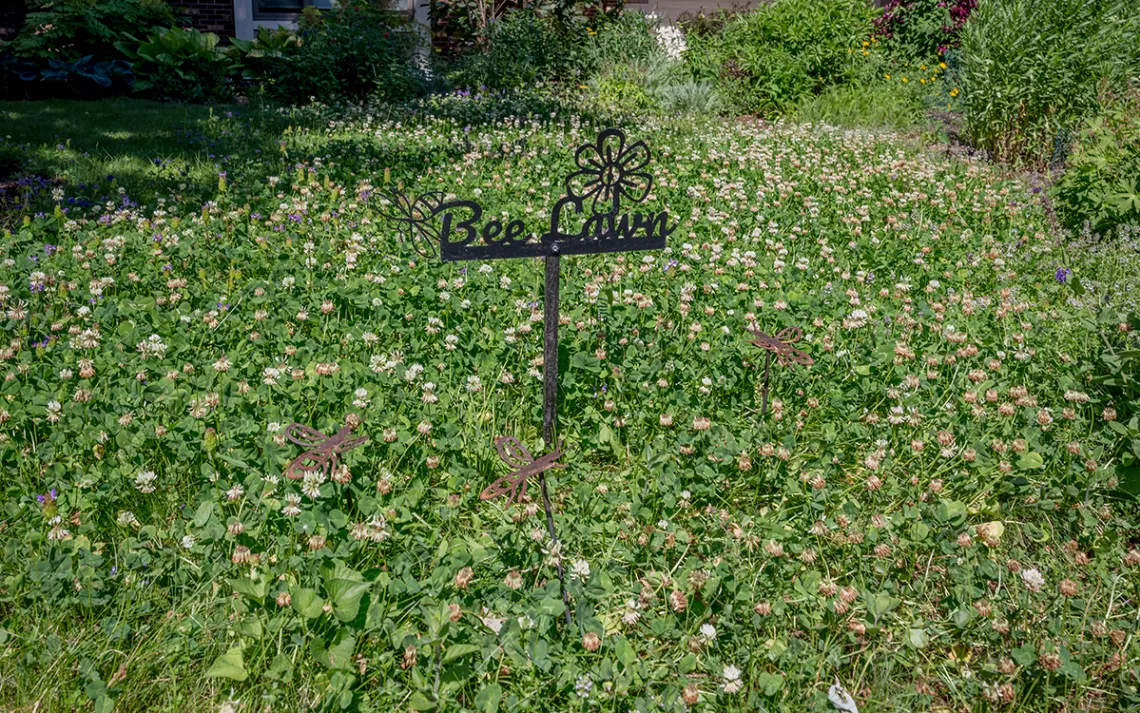

Laurie Pellerite, a retired schoolteacher and avid gardener, had already filled her flower beds with native plants but wanted to do more to attract pollinators. So, a few years ago she installed a “bee lawn” in her Woodbury, Minnesota, front yard.

“It’s just this thick, lush, sea of blossoms,” Pellerite told Sierra. “You can stand on the edge of the lawn and hear it buzzing.” An anomaly her lawn is not—rather, it’s part of a decade-long effort to transform Minnesota’s lawns into ecological boons.

Nearly one in four of North America’s native bee species are imperiled, in large part due to habitat loss. While lawns compose a whopping 40 million acres of land in the United States, most are effectively green deserts for bees.

Marla Spivak, a University of Minnesota professor and recipient of the MacArthur Foundation “genius grant” for her work on honeybees, hatched the bee lawn brainchild a decade ago. Riding her bicycle around Minneapolis, Spivak began musing about the city’s expanses of perfectly manicured grass: “Why do we think that’s beautiful, and how did that get started, this idea that a manicured lawn is desirable?”

Until World War II, white clover lawns were common, so Spivak wondered if homeowners today might embrace the concept of a flowering lawn. To find out, she teamed up with Eric Watkins, a professor and turfgrass specialist at the University of Minnesota who’s spent much of his career creating more sustainable lawns.

With research funding from the state, Spivak and Watkins developed a novel seed mix that combines white clover, self-heal, and creeping thyme with fine fescue (a.k.a. “no mow” grass). When they planted the seed in Minneapolis parks, they found the ensuing flowers attracted over 50 species of bees and supported a higher diversity of bees than lawns with clover alone. “It was very surprising,” Spivak says.

People took to the idea like, well, bees to honey. Surveys showed that over 95 percent of Minneapolis locals supported installing bee lawns in city parks. “There were a few fears about stings,” Spivak says, “but mostly people liked the idea.” The Minneapolis Park and Recreation Board took note, integrating bee lawns into its master development plans. “People asked for bee lawns,” says MaryLynn Pulscher, environmental education manager of the board. “They’re seeing the value and want to be supportive of it.”

State politicians also got on board. In 2016, Governor Mark Dayton created a pollinator protection task force intended to, among other things, raise public awareness of pollinator issues. Three years later, Minnesota created a Lawns to Legumes program that pays residents as much as $350 to convert their lawns into pollinator-friendly habitat. Bee lawns are one such project type that can receive funding. It was “really helpful information for us, knowing that incorporating flowers into lawns can have benefits to pollinators,” says Dan Shaw, senior ecologist at the Minnesota Board of Water and Soil Resources.

In its first year, the wildly popular program received more than 7,500 applications and was featured in Oprah magazine, says Shaw. To date, it’s received close to $3 million in funding.

But why install a bee lawn instead of native plants? James Wolfin, a conservation specialist and former graduate student of Spivak's and Watkins', encourages people to add native plants to their yards but notes that many residents want to designate some portion of their yard to gather and play. For those areas, “a bee lawn is a great tool,” says Wolfin. Native pollinator gardens can also look a little wild, chuckles Spivak in agreement, “like Jackson Pollock art.” While she and many others have installed native plant gardens, she acknowledges that “some people really want or need that manicured look,” which bee lawns can handily deliver.

Bee lawns are also proving to be an easy first step for people interested in integrating pollinator habitat into their yards. And, once people feel “the buzz” from that first conservation action, they often want to do more.

Once people feel “the buzz” from that first conservation action, they often want to do more.

Sandra Walto, a registered nurse, didn’t intend to install a bee lawn—at least not initially. She had planned to install a rain garden in her front yard in Eden Prairie, Minnesota. However, when COVID hit, her extra workload prevented her from attending the rain garden class she’d signed up for. So, she searched for other options and discovered bee lawns. “It seemed like something I could do on my own that didn’t require a lot of cost and not much effort,” she says.

That bee lawn was Walto’s entry point into at-home bee conservation. Since then, she’s added native plants to her garden beds. “The pandemic started it all,” Walto says. “You couldn’t go anywhere or do anything, so I started planting.”

Walto and Pellerite aren’t the only bee lawn converts—interest is sweeping the state. “If you talk to people that sell seed,” Watkins says, “they’re seeing a lot more of this seed mixture move.”

While only a few local garden centers initially carried bee lawn seed, Wolfin says it can now be found at large garden centers around the state, and that one, Twin City Seed, sells it throughout the country via Amazon. Wolfin adds that when he first started offering bee lawn workshops as a graduate student, attendance was in the single digits. Today, his workshops can hit the Zoom limit of 1,000 registrants.

Pulscher compares the growth trajectory of bee lawns to what happened with native plants, noting that in the 1980s, it was hard to find native plants and seeds, while today, she can bike to a local garden center and get 150 different native plants. “There has been an explosion of interest in bee lawns,” she muses, “in part because it’s so much easier to find bee lawn seed in garden centers now.”

Wolfin has also started to receive large-scale orders from municipalities. The Minnesota Department of Transportation, for instance, is interested in using bee lawns along roadways. And Minnesota’s Golf Course Superintendents Association now encourages local courses to install bee lawns.

Watkins hasn’t received complaints about bee lawns. Neither have Pellerite or Walto, who live in traditional neighborhoods where one might expect pushback (even in uber-polite Minnesota). Pellerite credits this, at least in part, to taking good care of her front lawn and keeping it weeded. “If you’re nontraditional, you can only push the envelope so far,” she says. “I wanted to make sure that what I have is clearly well cared for.”

The biggest bee lawn criticism is that clover (a non-native plant) is included in the seed mix. Spivak, however, points out that while we need more native plants in yards, bees really like clover. It’s attracting a lot of diversity of native species.” Indeed, Spivak and Watkins have found 56 bee species feeding on clover alone.

The benefits of bee lawns go well beyond pollinators. Traditional lawns require a lot of “inputs,” such as fertilizer, mowing, pesticides, and water, unlike the fine fescue grass used in the bee lawn seed mix. “Fine fescue has one-sixth the fertilizer needs of a traditional turfgrass lawn,” says Wolfin. “You can go four weeks without watering it, and you can mow it only three times per year.”

And then there’s the fact that in 2021, Minnesota suffered one of its most severe droughts. The following year, many parts of the state faced drought again. “People are really interested in growing grasses that don’t need to be watered as much, or will do better during a drought,” says Watkins. Thus, showing people that there are other more sustainable grass options—even if the people aren’t driven by a desire to help pollinators—is another important aspect of the team’s work.

The decade of research and development that has already gone into bee lawns is only the beginning. Researchers at the University of Minnesota and a few other institutions were recently awarded a $7 million National Science Foundation grant to study 80 bee lawns in Minnesota over six years. Turfgrass researchers at Mississippi State University are also developing bee lawns specifically for the southern United States, which is “a whole different system—different grasses, different pollinators,” says Watkins.

Overall, the bee lawn movement evinces an evolving view of lawns. Indeed, over the last decade, Spivak has noticed a shift in how people are managing their lawns in Minneapolis. She believes that the desire for a perfectly manicured lawn is changing. “I still ride my bike around, and now people’s yards and gardens are quite different, at least where I ride,” she says. “It kind of warms my heart.”

The Magazine of The Sierra Club

The Magazine of The Sierra Club