Mexico’s “Jaguar Warriors” Risk Their Lives to Save Big Cats

A team of researchers grapple with poachers, loggers, and narcos to track jaguars

Photo courtesy of Joe Figel and Rayo Garcia

Night is coming on, and the research team is in a hurry. We’ve been on the move since early morning, climbing into the upper reaches of the Sierra Madre del Sur along a web of smuggling trails and old logging roads. Hurtling from site to site in cuatrimotos (ATVs), we’re out collecting data from a series of camera traps meant to track the movements of jaguars and other big cats in the area. I’m here with an intrepid, rain-soaked, eight-person patrol made up of research students and local guides and headed by biologist Fernando Ruiz, one of Mexico’s foremost jaguar experts.

We made good time earlier in the day, but at higher elevations the trails are choked with bracken and debris, forcing us to clear the way with machetes. Midafternoon, it began to rain, the trails soon growing so slick that at times we’ve had to get down and push the cuatrimotos. Now it’s starting to get dark.

Dark is not a good time to be out and about in these mountains. Horned pit vipers are endemic to the area, as are five species of big cat. But the most dangerous predator to prowl these slopes walks on two legs. That’s because this part of the sierra—in rugged Guerrero State—is also cartel country.

One of Mexico’s most violent states as well as one of the poorest, Guerrero—sprawling along the coast of southwest Mexico—is home to several organized crime groups, including the powerful Jalisco New Generation Cartel (CJNG). About 60 percent of the heroin that enters the United States from Mexico comes from Guerrero, which is also a hotbed for the production of the synthetic opioid fentanyl.

“We know it can be dangerous up here, and we don’t take it lightly,” says Ruiz, as he kneels beside a camera trap strapped to the trunk of an encino sapling. “But we can’t let them scare us off. We’ve still got a job to do.”

Ruiz, who teaches at the National Autonomous University in the state capital of Chilpancingo, and his team have an ambitious plan. One goal of their “Jaguar Warriors” project is to form a corridor that will link existing pockets of big cats in this region with other parts of Mexico—up to and including the US border—to create space for a healthy breeding stock. A related objective is to curb illegal hunting and range reduction within the corridor.

Both goals require knowledge of jaguar movements. And that means taking the risk of running into the narcos. When I ask Ruiz if he’s ever thought about an armed escort, he just shrugs.

“Not even the army is safe in the sierra,” he says, referring to brazen cartel ambushes in Guerrero. Then he guns the engine of his ATV, turns on the headlights, and we start the long, wet trip back to the base camp.

Photo courtesy of Fernando Ruiz

Photo courtesy of Joe Figel and Rayo Garcia

The cameras we’ve been checking are triggered by motion sensors and can record both still and video images. They’re also equipped with night vision and infrared. In some six years of work, Ruis and his team have identified 18 individual jaguars by carefully studying the unique patterns of their rosettes, or spots. They’ve also discovered four other species of big cat living within the study area of about 40 thousand acres—puma, ocelot, jaguarundi, and margay.

And they’ve documented unexpected behavior—allegedly nocturnal jaguars out during the day and roaming in the chilly, pine-and-oak cloud forests as high as 8,000 feet. Perhaps most important, they’ve been able to study information about the cats’ interactions with farmers and ranchers with the hope that reduced poaching will expand their range.

In Guerrero, hunting and deforestation have combined to reduce the state’s jaguar population to about 120 animals, all of which remain highly endangered. At least seven cats were killed so far this year in the Tecpan Galeana municipality where the Jaguar Warriors project is based.

Part of the Warriors’ strategy to stave off jaguar extinction in Guerrero involves working with Mexico’s National Forestry Commission (CONAFUR) to reward campesinos (small farmers) for helping to safeguard the cats.

Many farmers live in land-sharing communities called ejidos, which take a cooperative approach to resource management. The Warriors use funds provided by CONAFUR to reward the campesinos for grassroots conservation. In the ejido of Cordon Grande, within the Tecpan district, more than 50 percent of community lands are protected, off-limits to farmers and cattle alike.

Such mountainous corridors “facilitate jaguar dispersal and therefore promote genetic diversity,” Dr. Joe Figel explains by email. He is a jaguar researcher with the Mexico-based Institute for the Management and Conservation of Biodiversity (INMACOB). “Throughout Mexico,” he says, “the greatest threats to jaguars are habitat loss and poaching.”

Unlike jaguars in the Amazon basin, those in North and Central America are “at much greater risk due to the greater extent of fragmentation across populations,” Figel continues. Illegal hunting of jaguars, often “in retaliation for livestock depredation,” remains an ongoing problem, despite attempts to compensate farmers for their losses.

A few days after the camera-trap excursion, I accompany the Cordon Grande comisariado—sort of a cross between mayor and sheriff of the ejido—to hear the complaint of a farmer who has lost several goats to a jaguar.

A jaguarundi caught on a camera trap

Photo courtesy of Fernando Ruiz

Photo courtesy of Fernando Ruiz

We ride horseback through high country covered with parota and higera trees. Red-winged vaquero birds call from the brush. We stop to drink from a spring just off the trail and the comisariado, whose name is Luis Casares, twists a large and fleshy leaf from a lampa plant into a perfect drinking vessel, complete with a stem for the handle.

Casares, 36, was only elected to his post a few months ago he tells me as we water the horses from the folded lampa leaves. In fact, he used to be a poppy farmer, like all his neighbors. But most of them have gotten out of the business. The opium market has crashed over the last year, replaced by synthetic opioids like fentanyl, and forcing farmers to focus on other revenue streams.

“Now they all want to run more cows, more goats. So they see the jaguar as a threat,” he says. “Many are jealous that they can’t clear more trees because of the cats.”

But Casares himself is an avid deer hunter, and as such he knows the value of the animal he calls el tigre.

“When we walk the forest, they flee before us. They aren’t like ocelots, who will live near humans. And unlike the puma, they don’t attack people. Also, the tigres control the deer and peccary so they don’t overpopulate and strip the woods—or come into our fields and eat the corn.”

We ride on to meet the farmer who lost his goats. His name is Dionicio Rodriguez, and he’s brought a neighbor as a witness. The jaguar came upon Rodriguez’s flock sheltered under a boulder on the side of a hill and killed nine of them in one night, but ate only one.

“It’s like it killed them all for sport,” says neighbor Rosendo Hernandez.

“Or out of spite,” says Rodriguez.

“We’re sick of jaguars around here,” Hernandez says. “There are too many of them, and they’re pests.”

When I ask them about the risk of jaguars going extinct in Guerrero, the men say they’re skeptical of such claims.

“The biologists don’t know everything,” Hernandez says. “Those things [jaguars] are all over these mountains. And the economy is very bad. We need our goats to live. Why should we suffer so the cats can eat well?”

The preferred method of killing a jaguar, Rodrguez explains, is to track it down with hounds until it’s treed and then shot. Such poaching is punishable by fines or even prison time, but because the hunter must be caught in the act the rules are rarely enforced.

“A friend of mine in the next village kills them with poison instead of shooting,” says Hernandez. That way the hide doesn’t get mutilated and will fetch a better price.

Photo courtesy of Fernando Ruiz

Photo courtesy of Fernando Ruiz

An ocelot caught on a camera trap | Photo courtesy of Fernando Ruiz

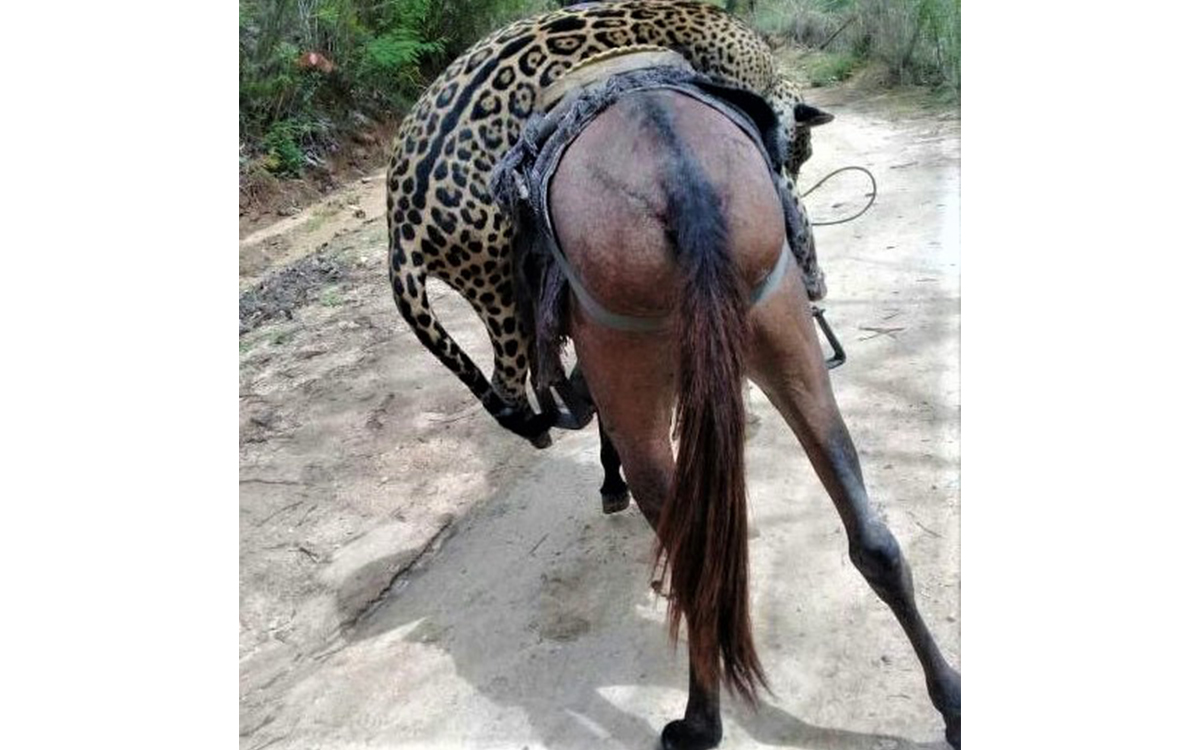

A poached jaguar | Photo courtesy of Elizabeth Muñoz

Thanks to grants from the CONAFUR, Casares is able to promise the farmer he’ll receive 2,500 pesos [$130] for each goat killed. Once we take our leave, he explains that the neighbor is confused about the number of jaguars in the area.

“Tigres are always on the move,” Casares says. “There can be a sighting here and then one the next day a few kilometers away and then again somewhere else, so the people think there are so many. But it’s often the same one showing up in different places.”

Then I ask him the same question I put to the farmer, about the cats dying out, and Casares frowns and shakes his head.

“I have heard them cough and growl in the night, in the woods, and it is like no other sound in the world. I would not like to think of a Guerrero without tigres,” he says. “I would not like to think of my children growing up in such a place.”

On their last night in Cordon Grande, the research team gathers in Casares's tin-roofed house in Cordon Grande. When they are out in the field, the team sleeps in tents set up in a clutch of old and battered cabins, without electricity or running water. Here in the village, however, the Casares family always opens their home to the Warriors, providing shelter and hot meals cooked on a wood-fired, clay stove.

As they sip coffee and nibble tortillas fresh from the comal, Ruiz and his students review the recently collected data from the camera blinds. Some of the researchers have made plaster casts of ocelot tracks they came across, and these are passed around with reverence.

There’s a sense of awe in the clean but humble casa. Grown men and women stand around a laptop, laughing like children over the retrieved photos and videos—exclaiming over a big male jaguar they’ve not seen in some time; a puma who looks to be pregnant; a female jaguar with a pair of cubs. They’ll stay with their mother for at least two years, Ruiz says. The species’ long adolescence means a female might only give birth to three or four litters during her lifetime.

The Warriors have applied for funding from a national conservation program sponsored by Volkswagen, and there is much hopeful talk this evening about what to do with the funding should they win. The communications director suggests eco-tourism as a long-term means of financial support for the project, although the presence of the cartels makes that dream seem unlikely to come true anytime soon. Another team member mentions expanding their outreach program to local schools, until someone reminds her that many of the children’s parents resent such programs, even as they resent the cats themselves.

I’m sitting in a camp chair taking notes when Ruiz comes over to hand me a mug of coffee. In response to a question about why he decided to specialize in jaguars in the first place, he cites the emblematic nature of the cats in his native culture, which made a deep impression on him growing up.

“The dances, the tigre masks, the costumes,” he reminisces. “The jaguar is mystical. Sacred. And that quality of charisma helps us. If we can convince people to save the jaguar, we can convince them to save all the animals in the jaguar’s kingdom.”

A few weeks later, Volkswagen will announce that the Warriors project won the grant, and so will receive just over $26,000 for research. On the same day the winner is announced, a poacher will post a series of photos on social media, posing proudly with another slain jaguar in the Tecpan sierra. Then reports will surface indicating the two cubs seen on the camera were also killed. Shortly thereafter, armed men from an unknown cartel in Guerrero will gun down a Discovery Channel photographer in a targeted assassination, sending a powerful message to journalists and environmentalists throughout the state.

That last night at Casares’s house, I ask Ruiz about the risk-to-reward ratio of his efforts in such a dangerous place. His response makes it clear he’s not about to back down anytime soon.

“I’m willing to risk my life for my work,” he says, in service to the “common conscience” of humankind.

“There is no sacrifice too great if it means that future generations will know el tigre still lives among them. And that they won’t be dressing up and dancing in honor of an animal they’ve lost.”

The Magazine of The Sierra Club

The Magazine of The Sierra Club