Many Utilities’ Net-Zero Commitments Amount to a Big Zero for Climate

The new “Dirty Truth” report finds power companies often prefer greenwashing to green energy

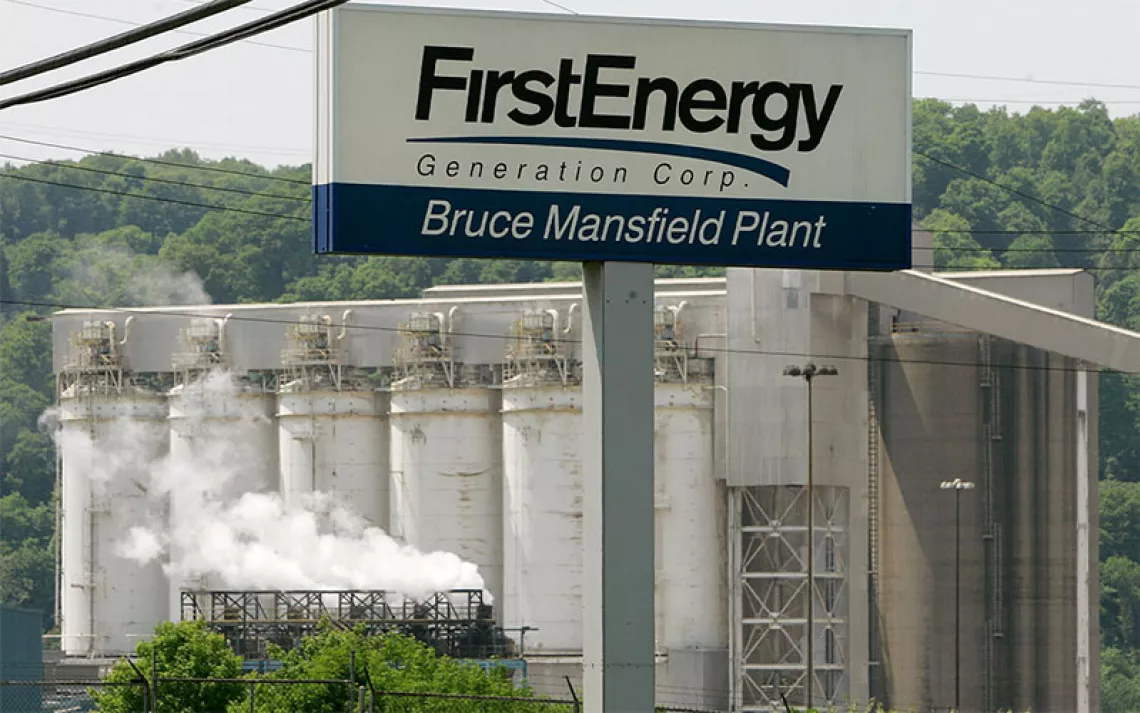

The Tennessee Valley Authority's Bull Run Fossil Plant. A coalition of environmental groups sued the EPA on August 25, 2022, over its refusal to regulate some older coal ash dumps, claiming they are polluting air and groundwater. | Photo by AP Photo/Wade Payne

For the United States to take meaningful action on climate change and draw down fossil fuel emissions to "net zero," it must transition the nation's power sector to clean energy. About a quarter of all US greenhouse gas emissions come from burning fossil fuels for power, such as coal, oil, and fracked gas. There will need to be a systemic change in how we power our homes, vehicles, and cities to tackle the climate crisis already underway.

When the utilities responsible for delivering that power commit to achieve “net zero by 2050,” the commitment—often publicized on social media, on websites, and in press releases—can be exciting. For example, Southern Company, a gas and electric utility based in Atlanta, tweeted on January 4 celebrating its 2050 pledge, and still has the tweet pinned to the top of its profile: “We’re taking action to achieve a net zero future for the customers and communities we are privileged to serve. Learn more about how we’re making strides towards our GHG emissions reduction goal of net zero emissions by 2050.”

The Twitter post, it turns out, is an example of how these companies are adopting clean energy rhetoric to distract from business as usual, according to The Dirty Truth About Utility Climate Pledges: 2022 Annual Report.

This is the second year that Sierra Club analysts investigated the climate action plans, or lack thereof, from 50 companies that own the 77 utilities most heavily invested in fossil fuel sources for energy (the first edition of The Dirty Truth was released in 2021). The report scores the companies from 0 to 100 for key variables, such as what progress those companies have made since 2021 to cancel plans to build new fracked gas plants, phase out dirty sources of energy such as gas and coal, and phase in clean sources such as wind and solar. The report assigns each company an overall letter grade and presents case studies examining whether the public statements utilities are making about their “net zero” plans have substance or amount to greenwashing.

The Dirty Truth reveals an energy sector defending the status quo over real change. When it comes to the crucial steps companies will have to take to achieve a real transition to clean energy—retire coal plants, build new clean energy infrastructure—the aggregate score for all companies studied was 21 out of 100, or a D. Of these, companies with climate pledges scored in aggregate nearly the same: also a D. Of all the utilities studied in the report, 28 scores dropped from 2021 and nine remained the same.

“Utilities have known that the federal government has a goal of transitioning to 100 percent clean energy by 2035, and yet we have not seen real progress from them since that last report,” Cara Bottorff, a senior analyst for the Sierra Club and one of the authors of The Dirty Truth, told Sierra. “It’s really disappointing.”

Electric utilities have spent more time in the past year and a half talking publicly about “net zero” pledges than pursuing real action to achieve that goal, according to the report. For example, while Southern Company might get an A for social media, it gets a lowly F for actual results. The utility has made no significant strides toward its net-zero pledge, analysts found, and has one of the worst records for keeping coal, one of the dirtiest sources of energy, online past 2030.

The report analyzes the public statements utilities are making about going net zero and compares those statements with a broad list of factors to evaluate whether they are following through. “We are seeing a lot of companies say that they are looking to be net zero by 2050,” Bottorff says. “But 2050 is very far away. We have to do things now, in this decade, by 2030. There is this overall greenwashing trend of setting very far-out goals like 2050. You might as well not have a goal at all, because at that point, we would have already overshot our carbon budget, accelerating a climate crisis already underway.”

Near-term goals such as reducing C02 emissions by 2030 aren’t immune to greenwashing. Without clear checkpoints, including a timeline and accountability process, those goals are also meaningless. According to the findings, many utilities that have committed to 2030 climate goals score similarly to those that don’t, because they lack such concrete benchmarks.

Still, the report did find signs of progress. The small portion of companies that have committed to the goal of making at least 80 percent emissions reductions by 2030 do better than the aggregate, with an average score of 43. The report shows that if utilities make specific promises that are timebound, they tend to score better than others that don’t.

In the first 2021 report, 17 of the 50 companies analyzed had no clean energy goal at all. In the current report, only 10 of those have no goal, showing that adopting some kind of clean energy pledge is becoming more common. Those parent companies that still have no clean energy goal score, on average, a rock-bottom 6 out of 100.

“These dirty utilities that are so critical to cleaning up the energy sector are not making the plans necessary to get to 80 percent clean power by 2030 and 100 percent clean energy by 2035,” says political scientist and energy analyst Leah Stokes. “It’s a little bit like procrastination. You can’t wait the night before a homework assignment is due to get started. These things take time. You have to be planning and working every day to make progress, and we just aren’t seeing that timely progress being made. If we don’t cut carbon pollution in half by 2030, we will blow past the 1.5°C warming target.”

Climate scientists affirm that industrial nations will have to cut carbon pollution in half by 2030 to limit warming to 1.5°C per the Paris Agreement. The warming already underway has been linked to extreme weather events such as severe droughts in the Southwest and destructive hurricanes and typhoons—just a glimpse of what’s to come if no action is taken.

"Hurricane Ian is a massive wake-up call to what the future will look like if we don’t make good on these climate pledges,” Susannah Randolph, senior campaign representative for the Sierra Club’s Beyond Coal campaign, said from her home in Florida the day before Ian made landfall. She had just returned from purchasing supplies while bracing for the storm. “We’re out of time. We’re out of excuses.”

Sign up to receive Sierra News & Views

Get articles like this one sent directly to your inbox weekly.

With this action you affirm you want to receive Sierra Club communications and may vote on policy designated by the Sierra Club Board.

The largest utility in the state, Florida Power and Light, announced in June a “Real Zero by 2045” pledge to eliminate its carbon emissions. The Dirty Truth gave the company a B for the work it’s doing to follow through on that pledge, such as plans to retire all of its coal by 2030. “Florida Power and Light acts as a trendsetter for the rest of the utility sector in the state,” Randolph said. “Its Real Zero pledge is ambitious and could set the stage for a rapid decarbonization for other utilities in the state.”

Florida Power and Light, though, is also an example of how even utilities improving their record on clean energy can present a mixed story. While the company is ramping up clean energy programs and battery storage technologies, it still holds a 33 percent stake in the Mountain Valley Pipeline, which, if completed, would carry 2 billion cubic feet per day of fracked gas from West Virginia across southern Virginia—a major source of the potent greenhouse gas methane. The company also has a poor record on energy conservation.

“When any company makes claims about ‘net-zero emissions’ or going ‘carbon neutral’ by some year, my greenwashing alert flag goes up,” says Bill Moll, the conservation chair of the Tennessee Chapter of the Sierra Club. “What counts is a company reducing its own carbon footprint in an overall environmentally sound manner. Subtracting dubious carbon credits from a company's carbon emissions for what someone else is purportedly doing to go ‘company negative’ is irrelevant to a company's responsibility for its own actions.”

The largest public utility in the nation, the Tennessee Valley Authority (TVA), is located in Moll’s backyard. The utility gets an F in The Dirty Truth report for its largely aspirational goal of reducing C02 emissions by 70 percent by 2030 and 80 percent by 2035. TVA also has a “net zero by 2050” commitment (click here for a feature article on the utility in Sierra’s Fall 2022 edition).

“TVA is the Tennessee Valley community,” Moll says. “In the TVA Act, it stipulates that the utility’s purpose is technological innovation, low-cost power, and environmental stewardship. We hope the utility can work to live up to those principles. It should take the time, effort, and money, and the engineering talents they have and move to economical, environmentally responsible mass energy storage. That would be a start. And they should avoid making enormous investments in gas plants.”

The push to clean up the nation’s power sector got a boost with the passage of the Inflation Reduction Act, which directs $370 billion for clean energy programs, including new tax incentives for the build-out of clean energy infrastructure, along with direct pay available for smaller utilities that don’t want to take the money through tax pathways. The bill also makes loans and grants available to help utilities transition off fossil fuels. The programs will be good for consumers, too, by lowering energy costs over time.

"If we can clean up this sector, we can reduce emissions by a quarter,” Bottorff says. “But we need to do more. Transitioning the electric sector to clean energy unlocks our ability to clean up other sectors. With clean energy, we can electrify transportation, for example, another big chunk of emissions. We must have clean energy to help decarbonize other sectors of our economy.”

The Magazine of The Sierra Club

The Magazine of The Sierra Club