A Letter From Phoenix

Record-breaking heat is the latest signal of a climate in crisis

A bus stop in Phoenix where a man was found slumped over on a day when temperatures reached 118°F.

On July 22, a little after 11 a.m., a man was found slumped over on the bench at a bus stop in front of the Walgreens near my house in Phoenix, Arizona. Workers there attempted to revive him. When that failed, they called 911, but it was too late. My wife happened to be driving by just as emergency workers pulled a white sheet over his face.

“I don’t know for sure,” a worker at the store told me soon after that, “but with this heat, it’s probably got to figure into what killed him.” That does seem likely. The temperature was around 108°F at the time. The medical examiner’s office for Maricopa County, which includes the Phoenix metropolitan area, reported 82 confirmed or suspected heat-related deaths in their latest update, issued on July 15. Eight out of 10 heat deaths occurred outside and half of those who died were homeless.

I don’t know if this victim was unsheltered at the time, but that seems likely too. When I went to the bus stop, the man’s blue blanket was still balled up on the bench. On the ground beneath it were a few pennies and a gallon water jug, empty, with the plastic cap lying nearby.

I’ve lost count of how many records we’ve broken.

A record-shattering heat wave is dominating this city with high temperatures at or above 110° for 27 days in a row. At this writing, an enormous heat dome is still parked over the Southwest, including Phoenix, America’s hottest large city. On the day the man died, the high temperature reached 118°, a record for that date.

I’ve lost count of how many records we’ve broken. The first to fall was when the string of 110-plus-degree days reached 19, breaking a record set nearly 50 years ago. That was followed by the highest low temperature ever recorded (97°), the highest daily average temperature (108°), the longest stretch of nights with temperatures not dropping below 90°, the first large American city to go a month with daily average temperatures (both day and night) of 100°, and many more. At this point, all I know is that we’ve broken a record number of heat-related records.

I knew Phoenix was an extreme environment when I moved here over two decades ago. It is, after all, in the middle of the Sonoran Desert. But the desert is why I moved here. I discovered I’m a “desert rat” at heart when I went to the University of Arizona in Tucson. I fell in love with the place—the giant saguaros and ocotillos, barrel cacti, cholla, the lizards, and countless bird species, the pungent scent of creosote that fills the air during monsoon season, and, yes, even the heat itself.

Most people move here despite the extreme environment, certain that air conditioning will get them through the hot summer months so that they can enjoy the delightfully temperate fall, winter, and spring. But in the toolkit of heat adaptation, air conditioning is the technological fix we reached for first despite the fact that it should be the method of last resort—after planting shade trees, installing green or light-colored roofs (black ones are still the most popular), and using cool pavements that don’t absorb the sun’s heat, releasing it at night. Air conditioning indoor areas increases the heat outside while also requiring an enormous amount of electricity, too often generated by burning fossil fuels—a vicious circle that leads to even higher temperatures. Air conditioning also strains the electrical grid, making power failures more likely. The loss of electricity in Phoenix during the summer would be catastrophic. A power outage lasting five days during a heat wave like the one we’re in now would result in the deaths of 13,000 people, according to a recent study.

And even with air conditioners running at full tilt, global warming has reached the point when the summer heat can’t be ignored. This July is unlike the other 23 summers I’ve experienced in Phoenix, when the effects of brutally hot days were offset by cool desert nights. The lethal impact of heat on the human body is cumulative. If you’re young, healthy, able-bodied, and have plenty of water and shade, you might survive several days in a row of extreme heat. But if your body can’t cool down and recover at night, those same conditions will kill you.

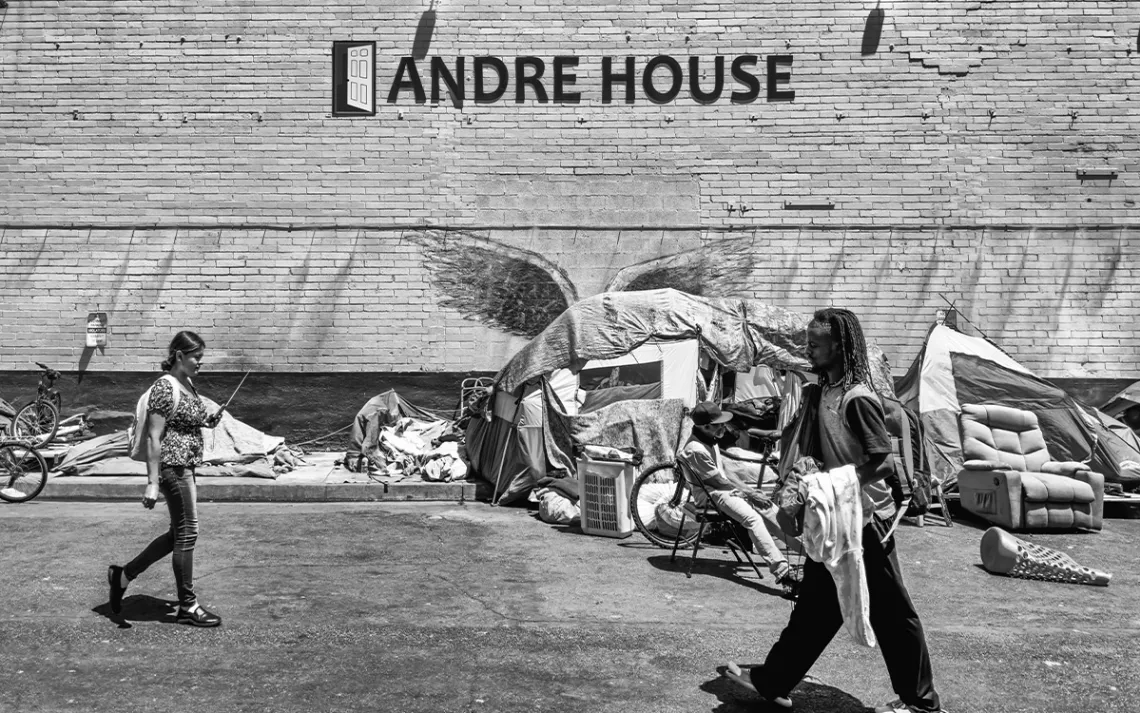

Scenes from an encampment of the unhoused in Phoenix known as "the Zone."

Like most other Phoenicians in my zip code, with the heat dome above, I’ve been spending most of the day inside my air-conditioned home office where the temperature is 82° for most of the day. But different zip codes within Phoenix may as well be on different continents. Like every large American city, location here is a surrogate for wealth, and wealth is a surrogate for survival in extreme heat. That’s particularly true in Phoenix today because of an acute affordable housing shortage. Only 22 percent of homes sold last year were affordable for families making the area’s median income, compared with 42 percent of houses sold nationally.

Some of the homes I’ve visited in upscale zip codes are as cool as an autumn day in New England. People in less wealthy zip codes have air conditioners, but their houses are often uncomfortably warm, the thermostat turned up a few degrees to avoid budget-busting electric bills. Many elderly people, who are just scraping by on Social Security, live in the poorest zip codes, where a lack of shade trees and irrigated lawns contribute to temperatures several degrees warmer than in wealthier neighborhoods. Some have air conditioners, but their old window units may be broken or their AC may simply be off. After paying rent and buying food and medicine, cool air is frequently a luxury that lies beyond their means. But even they aren’t the worst off. That distinction belongs to the estimated 7,000 unhoused people living in a city with just over 3,000 shelter beds.

Phoenix may be a canary in a coal mine, but it’s a coal mine from which none of us can escape—unless we end carbon pollution, quickly and completely. Whether the end comes from floods, wildfires, hurricanes, or heat, is ultimately irrelevant.

Phoenix has been called America’s least sustainable city. I don’t think that’s true, but even if it is, that characterization gives other places a false sense of security. This last July 4, Phoenix reached a sweltering 113°. But it was also the hottest day ever recorded on the planet. And now, in addition to the Southwestern heat dome, other high-pressure domes have formed over the northern hemisphere, bringing lethal temperatures to Siberia, Europe, and Asia. The problem is global.

Phoenix may be a canary in a coal mine, but it’s a coal mine from which none of us can escape—unless we end carbon pollution, quickly and completely. Whether the end comes from floods, wildfires, hurricanes, or heat, is ultimately irrelevant. What really matters is the fact that on a warming planet, there are no safe places.

The Magazine of The Sierra Club

The Magazine of The Sierra Club