Heat’s Deceptive Nostalgia

Don’t let memories of summers past prevent you from seeing the dangers of heat waves in today’s changed climate

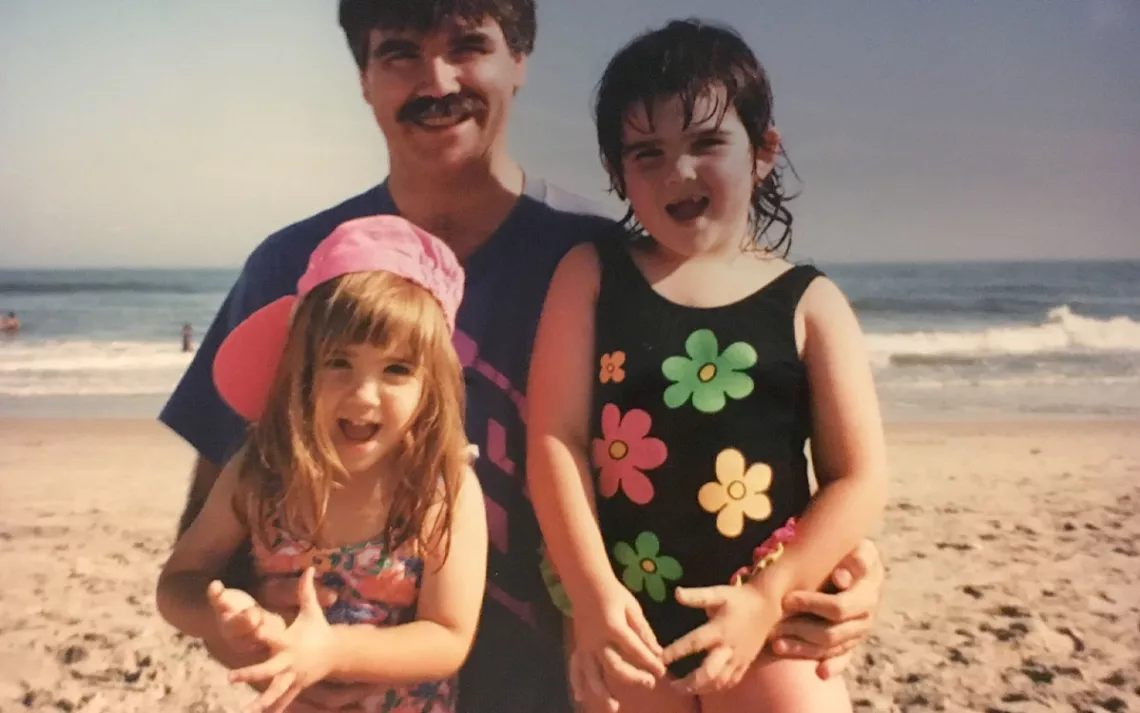

The author (left) with her father and sister finding summer relief at the Jersey Shore in the 1990s. | Photo courtesy of Colleen Hagerty

Growing up in New Jersey, there was a swell to the start of my summers. What began as a gentle heat, the sort that might draw sweat from your skin only after dedicated time outdoors, would turn full and all-encompassing by July. It radiated from the sun; it was in the air around you, carried by breezes that blew hot and damp.

This type of heat invited my friends and me outside, away from classrooms and supervision, and into extended playdates timed to the late-setting sun. It was also a temporary state—the promise of relief was never too far away. I could wave down a roving ice cream truck, lay my sticky skin onto the cool dewy grass, or jump into the always packed (but somehow still freezing) public pool. I could go inside my air-conditioned home, open the refrigerator, and pour myself glasses of water until the chill filled my stomach.

As a reporter who covers extreme-weather-related disasters, my memories of these summers now clash with my knowledge of how dangerous a hazard heat can be. If you’ll briefly indulge my journalistic reflex to share the statistics, the World Health Organization recognizes heat stress as the leading cause of weather-related deaths, killing an estimated 489,000 people worldwide annually. Extreme heat is also tied to an uptick in emergency room visits, fertility issues, and violent crime. And there are scores more studies about the many ways heat is impacting us as climate change continues to drive baseline temperatures higher.

We’ve reached a point where records are made and immediately broken: this July, we lived through Earth’s hottest day on record, only to do it again the next day. Researchers are trying to redefine what even constitutes a heat wave in this new climate. Already, the term is loosely defined by the National Weather Service as “a period of abnormally hot weather generally lasting more than two days,” purposely vague in order to accommodate the many climates within the United States. But what happens when the abnormal becomes normal? How do you warn people of an emergency that’s happening daily?

When will they stop caring? When will they start?

Whenever I write about heat, I think of a man I met in New York City’s Astoria Park in 2012. I was working for a local television station, and I had been sent out to do the sort of man-on-the-street interviews that fill the time between breaking stories. The city was in the midst of a heat wave, which New York City defines as at least three consecutive days above 90°F, and my task was to talk to people about how they were dealing with the weather. This, according to the man I stopped, was a silly question.

It’s the summer in New York City, he said. Of course it was hot.

Some amount of heat is an anticipated feature, not a bug, of summers in the Northeast. But this familiarity can create a false sense of safety, acting as blinders to the realities of our changing climate.

In the opening chapter of The Heat Will Kill You First, published in 2023, Jeff Goodell does not focus on a particularly extreme example of high temperatures but instead looks at what happened on a day that started off deceptively normal. The climate reporter shares the story of a young family who went out on a hike on what turned into a 100-degree day and never made it home. The parents, their infant, and their dog had died on the trail after exhausting their water supply.

Goodell titled the chapter “A Cautionary Tale,” and it’s an entry into what’s becoming an increasingly crowded genre. So far this summer, at least five hikers have died after setting out on their own hot-weather treks in state and national parks. Children are dying during outdoor gym classes, and their parents are dying at work. In many cases, these people were doing something they’ve done countless times before, without realizing that things were different until it was too late.

Heat is silent, Goodell cautions. It lacks the drama of smoky skies or the warning of a clap of thunder. It’s harder to point to the moment things change, and it’s harder to know when you become at risk.

Heat is also personal. Like pain or love, it’s something we each experience and gauge in our own way, making it difficult to standardize. While there are some scientific thresholds of what the human body can and can’t handle, we each have our own windows of preferred temperatures and humidity. We each have our own memories of heat and what we feel confident we can withstand. Temperatures that feel unbearable to someone in Maine might be routine to someone in Arizona; different cities and states have varying thresholds for heat emergencies depending on their historical temperature averages, infrastructure, and socioeconomic makeup.

That means recognizing heat as a threat requires coming to terms with our own vulnerabilities. Heat disproportionately impacts people who have underlying health conditions, who are both young and old old, and who have lower incomes. At some point, we will all fit into at least one of these categories, but we don’t always recognize it in ourselves. Researchers from the University of Albany have been looking into how heat risk communication misses the mark by using blanket terms like “elderly,” which can be misinterpreted and easily dismissed. “You know, I’m 75. I don’t consider myself elderly,” one focus group member told the researchers (the Centers for Disease Control considers anyone 65 and up to be at heightened heat risk).

I’ve spent the past six years living in Los Angeles, a city famous for its sun-soaked, perma-pleasant weather (though that, too, is changing). The first summer I returned to New Jersey, I felt nauseated for days. I wondered if I was sick, only to realize my stomach would churn each time I lingered outdoors in the humidity. This, from the person who stood outside unaffected for hours interviewing people during a heat wave. I was no longer accustomed to this sort of wet heat. Embarrassed, I joked that LA had made me “weak,” and I reflexively pushed myself to get past my discomfort.

I’ve reported outdoors on some of these record-breaking days, telling myself that this is nothing compared to what so many of the people I’m interviewing have been dealing with. I’ve let these thoughts convince me to linger outside despite my body’s protests. Off the clock, I’ve driven past highway signs warning of extreme heat on my way to a hike and swiped away emergency notifications on my phone.

I’ve felt comfortable doing this because I’ve done it before, and because I’ve been lucky—lucky enough that the promise of cool relief has never been too far away. But that’s something I know I shouldn’t be taking for granted anymore.

The Magazine of The Sierra Club

The Magazine of The Sierra Club