This North Carolina Hamlet Faced Hurricane Helene With Intent

Could intentional communities like Celo offer a blueprint for new climate harbors?

With the public schools shuttered after Hurricane Helene, teachers launched a makeshift outdoor school in Celo for any kids who could get there. In the days just after the storm, kids talk through and draw responses to how they experienced the storm. | Photo by Jeff Goodman

In the depths of the Great Depression, the flood engineer Arthur E. Morgan, head of the Tennessee Valley Authority and president emeritus of Ohio’s Antioch College, searched large tracts of river valley for sale in the Southern Appalachians to stake an idealist experiment: If given land and development support, could people wrecked by the nation’s economic, industrial, and environmental ills come together in rural regions and build intentional community?

Morgan believed that seeding small communities across the nation would build culture and resilience, and help keep wealth local. He planted one such seed in the Black Mountains of western North Carolina in 1937. Morgan convinced a conservative industrialist to buy 1,250 acres of forest and farmland in the Toe River Valley, about 50 miles northeast of Asheville, and to fund initial development of a community called Celo. It is now one of the oldest intentional communities in the United States not run by a religious organization.

My father-in-law, Paul Hoover, first walked Celo’s tranquil stretch of the South Toe River in 1958 as a 19-year-old Antioch undergraduate. On the morning of September 27, 2024, Paul, now 85 and Celo’s second-oldest resident, watched Hurricane Helene’s torrents turn the river into a slurry of debris and uprooted trees. The muddy onslaught swept away Celo’s food co-op and mountain-crafts store; gutted the Celo Inn; and severed roads and the bridge to the community before the South Toe peaked at a record 25 feet above normal.

Following Hurricane Helene, Celo residents gather at the destroyed bridge that leads into the community. Many crossed using the ladder shown on the right. | Photo by Tal Galton/Snakeroot Ecotours

Within hours of the storm, Celo members had accounted for most of their 54 families and nearby neighbors. At 4 p.m., they gathered and broke into teams: some to check on surrounding neighbors, others with tractors and chainsaws to clear roads and trails so every house could be accessible in case of cascading emergencies. Paul’s house became a water-filling, tool-charging, and hot-shower station, saved from water and power outages by the gravity-fed spring and off-grid solar system he built in 1980.

It's what has happened since the flood that makes intentional communities like Celo potential models to support Americans seeking refuge from climate-charged calamities like Hurricanes Helene and Milton. “There is no safe place to live, but there are good places,” said Cedar Johnson, 46, who was raised in Celo and returned with her husband, Ben McCann, to start an organic farm and raise their children, Robyn and Naomi, there.

The South Toe River rose 25 feet above normal during Hurricane Helene, drowning Celo’s common areas. | Photo by Tal Galton/Snakeroot Ecotours

When she saw the South Toe River engulf the bridge, rebuilt after a 1977 flood to withstand imaginable storms, Johnson’s mind went to her teenagers. At least Robyn was safe at college at the University of North Carolina in Asheville and wouldn’t face the chaos Naomi was about to, she thought. The family spent the next hours wading through floodwaters and bushwacking to the homes of more-vulnerable neighbors to lead them to safety.

“On-the-ground operations in the North Carolina mountains have been defined by compassion rather than conspiracy."

As it turned out, Robyn had to flee Asheville, which still lacks clean drinking water three weeks after the storm. UNC-Asheville classes will not resume until October 28, and then online. Johnson has reappraised which child was safer. “We were equally damaged,” she said, “but [Celo] had many more resources.”

In the wake of the disaster, the family has donated their farm’s harvest to flood victims in the South Toe Valley via the Celo Community Center, which became a hub for daily post-storm meetings drawing more than 100 area residents.

Such resourcefulness and generosity have marked the response to Helene throughout the largely rural swath of six states ravaged by the hurricane. The far-right extremists, disinformation dealers, and chaos-sowing politicians who have harmed relief efforts are mostly outsiders. On-the-ground operations have been defined by compassion rather than conspiracy.

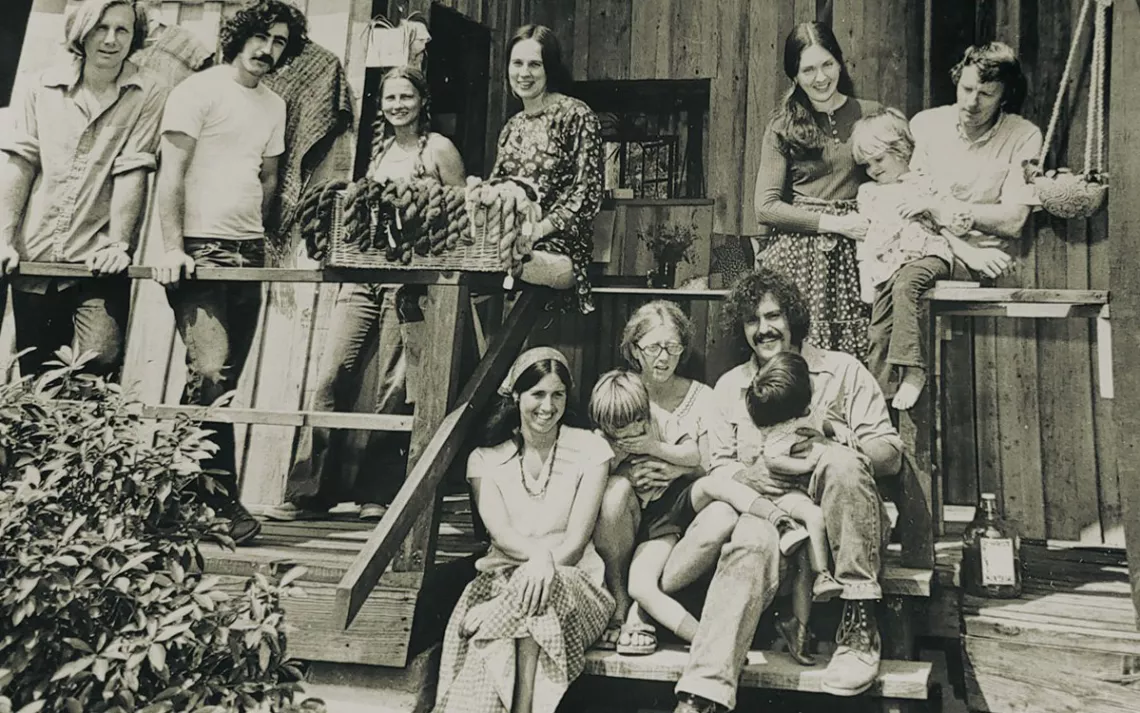

The Toe River Crafts store in Celo on opening day in 1974. | Handout

In her book A Paradise Built in Hell, Rebecca Solnit writes about how extraordinary community arises from disasters because, “in the suspension of the usual order and the failure of most systems, we are free to live and act another way.” Beyond just clawing out from failure, extraordinary community can also be the system that lays out an effective course to recovery. Celo’s founding documents made cooperation and care for the environment the usual order. Organized as a land trust with the great majority of acreage left wild, members lease their holdings and manage community business and commons areas by consensus, a Quaker influence that runs through Celo’s past and present.

Its 90-year history shows that sustainable communities can be planned. They can be built with solar and integrated farms. They can be launched by philanthropists, NGOs, government grants, or combinations of those. In the face of repeat climate disasters set to force millions of Americans fleeing from the nation’s riskiest areas, they can be deployed with intention, on a much larger scale, to make new ways of living available and affordable for more than a few.

Jeff Goodman and Margot Atuk joined the Celo community 30 years ago after meeting as young teachers at Arthur Morgan School—Celo’s middle school with a working farm. They recently retired from Appalachian State University and the Yancey County public schools. With public schools shuttered in the wake of the flood, they and other teachers have launched a makeshift outdoor school for any kids who can get there. Four students showed up the first day; last week there were 25. The high schoolers discussed college essays. The middle schoolers wrote poetry from the river’s perspective:

I tasted a road.

I swept away houses.

For science, kids worked on energy and electricity, building circuits with small solar panels, motors, and LED lights and learned about currents, voltage, and how generators work. For math, the young ones calculated how many board feet of lumber could be salvaged from downed trees.

“Beyond just clawing out from failure, extraordinary community can also be the system that lays out an effective course to recovery.”

The novelist Anne Tyler lived in Celo as a child; she tells the story of how, when her family moved away to Raleigh in 1952 when she was 11, she could strike a match on the sole of her bare feet but had not yet used a telephone. Johnson, the organic farmer, said her life’s work was sparked tending the garden at Arthur Morgan School. My husband traces his love for splitting firewood to his seventh-grade Arthur Morgan School teacher who taught him how.

All of that might sound like a training ground for individual self-reliance. And that was, in fact, the vision of the Chicago textile mogul who underwrote Celo’s land purchase and seed capital. William Regnery “harbored a nostalgic belief that people who lived in rural villages and earned their living by subsistence farming constituted the virtuous and self-reliant bedrock of republican government,” writes Timothy Miller, a University of Kansas scholar who researches the history of intentional communities in America.

Toe River Crafts artists set pottery and other works out to dry following a major flood in 1977. | Handout

But that vision clashed with Arthur Morgan’s, and Regnery did not last as Celo’s benefactor. Goodman points out that Celo evolved much closer to Morgan’s goals for a shared commons and mutual support than it did a millionaire’s myth of Jeffersonian self-sufficiency. The Helene disaster underscores the extent to which community members—who were viewed with suspicion in Yancey County in Celo’s early years when it drew conscientious objectors during World War II—ultimately wove into the fabric of the South Toe Valley. They became public school teachers, firefighters, health providers, farmers, other local business owners, and part of the valley’s significant collective of artists.

Make every day an Earth Day

Get articles like this one sent directly to your inbox.

With this action you affirm you want to receive Sierra Club communications and may vote on policy designated by the Sierra Club Board.

During the storm, as the wind whipped the trees, Goodman wore a red bicycle helmet as he checked on neighbors. At their gathering that first afternoon when the rains had passed, he led community members in a rendition of the folk song “The Water Is Wide.” It is not exactly a picture of Rambo resilience in end times. And community members stress that Yancey County and other responders—especially the arrival Sunday morning after the storm of volunteers from South Toe Fire & Rescue who rolled up with excavators and made the bridge crossable—have been pivotal to recovery. Celo “is really about interdependence,” Goodman said.

“It’s not like we had planned all the right things or put aside the right things,” he said. The food co-op’s idea of storm preparation—raising its 50-pound bags of oats to high shelves to stay dry—didn’t matter when the whole building washed away. “It’s more that when tragedy struck, we knew how to have one another’s back to the best of our capability, and to be sensitive to the grief that people were going through.”

Hurricane Helene wiped out the 50-year-old mountain-crafts store and Celo’s food co-op next door. | Photo by Tal Galton/Snakeroot Ecotours

That’s a fine definition for modern intentional communities, which need not be pastoral. Urban examples include cohousing built around themes like single-parent families or tech workforces. Bastion, in the Gentilly neighborhood of New Orleans, was made for veterans who served in Iraq and Afghanistan. Las Abuelitas Kinship Housing in Tucson is centered on grandparents raising grandchildren.

Intentional communities ordered around sustainable agriculture, solar and renewable tech, the arts, and other themes are especially well-suited to places suffering economic losses and population declines, including in interior north Florida, the Carolinas, and the Rust Belt. People relocating from riskier flood zones or mountain slopes need not entirely abandon place; intentional communities can be planned for the safest close location possible. These kinds of creative climate transitions are urgently needed in regions with repeat disasters.

But so far, planned climate harbors like Florida’s Babcock Ranch remain unaffordable for many working families and older Americans whose retirement dreams have been wiped out in disasters. Rural counties, meanwhile, have been shut out from large-scale philanthropy and federal infrastructure grants given their lack of financial and professional resources and time to compete.

The anthropologist Joshua Lockyer, who wrote Celo’s story in his book Seeing Like a Commons, points out the irony that Arthur Morgan created the community as an experiment in the commons in Appalachia. As the first chairman of the Tennessee Valley Authority, Morgan “had just finished imposing an industrial-scale, state-based development program on local residents,” Lockyer writes, “massively displacing local populations and contributing to ongoing processes of commons enclosure and dispossession.” Morgan envisioned planned worker villages throughout the TVA region but built only one, Norris, which excluded Black residents.

Then Tennessee Valley Authority chairman Arthur E. Morgan founded Celo as an intentional community in 1937. Unlike his vision for TVA communities, he carefully avoided prescribing detailed goals for Celo, but wanted to create a place for people with shared values to build their own version of community. Here Morgan arrives at the White House in March 1938 to join a special meeting called by President Roosevelt. His one-time champion pushed him out that same month over clashes with fellow directors who rejected his vision of the TVA as a force for life-changing regional planning versus the narrower technical aims of power production and flood control. | Photo courtesy Library of Congress

A converted Quaker, Morgan spent later years on racial and social justice issues, including helping the Seneca Nation fight the federal government’s plans to drown a third of its Allegany reservation for Pennsylvania’s Kinzua Dam. Morgan was in the middle of fighting that battle—later lost—in the late 1950s when my father-in-law met him at Antioch College. Morgan, tall and always formal in a suit and tie, taught his courses in the parlor of his colonial-style home in Yellow Springs.

One of those courses, “The Small Community,” led Paul to Celo. As an undergraduate, he helped build the school’s walls from South Toe River rock. He has spent his days since Helene helping neighbors install emergency solar.

Morgan’s older years were also filled with purpose. “The Small Community” and another Antioch course, “Dams and Other Disasters,” became two of his more than 20 books, the latter a 422-page takedown of the Army Corps of Engineers published in 1971, four years before Morgan’s death at age 97.

In that book, he quoted from proverbs: Where there is no vision, the people perish.

Arthur Morgan’s ultimate vision of intentional community was neither state-based nor spiritual commune nor survivalist bunker. It was not a utopia like New Harmony, Indiana, or Oneida, New York, whose reliance on eccentric leaders helped caused their collapse. It was not a religious regiment like the Shakers, Mennonites, or Amish.

The guiding spirit was the intention of people who wanted to come together, in the case of Celo, to live simply and cooperate on behalf of the common good in the face of what Morgan described as the “staggering shocks” brought on by industrial development. He could have been describing climate change.

Celo succeeded on a number of fronts, not least sustaining new generations in mutual support; as its elders remain vital, the community this year welcomed two new babies. But it is only one seed—at a time when the world needs a whole forest of safe shelter and care for the common good.

The Magazine of The Sierra Club

The Magazine of The Sierra Club