Nearly 100 Community Water Systems in California Contain Illegal Levels of Arsenic

A new report clarifies the extent to which poor and rural communities still lack basic access to water

Maricela Mares-Alatorre at a September 8, 2016 El Pueblo and Greenaction community meeting. Photo courtesy of Greenaction.

Maricela Mares-Alatorre has lived in Kettleman City, a small, unincorporated town in Kings County, California, for 39 years. A largely farmworker community hugging State Route 41, Kettleman City is home to pistachio growers, cattle producers, cotton fields, and sprawling fruit orchards. The California Aqueduct runs right past the town—ferrying water from the Sierra Nevada to farms and cities, and serving millions of people throughout the state.

Mares-Alatorre hasn’t poured a glass of drinking water from the tap since she was in high school. Her eight-year-old daughter has never done so.

“In the Central Valley, we have a lot of pistachio growers, and their trees get better water then we do,” she says. “That’s not right.”

The groundwater in Kettleman City is contaminated with arsenic in amounts that are well in excess of federal safety standards. And Kettleman City isn’t alone. It is one of 95 public water systems in California with arsenic levels that failed Safe Drinking Water Act standards in 2014 and 2015, according to new data released on Monday by the Environmental Integrity Project (EIP).

“Every American has a right to clean and safe drinking water,” says Eric Schaeffer, executive director of EIP. “But the contamination of Flint, Michigan’s water supply earlier this year reminded us that we can’t take those rights for granted. That’s especially true for lower-income citizens and minorities.”

Researchers from EIP, after reviewing two years of state records, documented multiple cases of arsenic-contaminated water in systems that serve more than 55,000 people statewide, with poor and rural communities affected the most.

“Almost all of these systems violated the arsenic limit for at least the past five years, and probably longer,” Schaeffer says.

California has a long history of drinking water problems. Many communities exposed to the polluted water are poor and/or Latino or African American, according to the report Arsenic in California Drinking Water. In the most egregious example, a home for troubled teenage boys in Madera County, the Valley Teen Ranch, had water with arsenic concentrations averaging more than 12 times the federal limit of 10 parts per billion.

Arsenic is a poison if consumed in high concentrations. According to the World Health Organization, there are a number of health risks to drinking high levels of arsenic over time, including bladder cancer and skin lesions. There is also some evidence that it contributes to diabetes and is a risk factor for cardiovascular disease.

Dr. John Balmes, a professor of medicine at the University of California at San Francisco and a professor of environmental sciences at the UC Berkeley School of Public Health, was part of the group of researchers who first discovered a correlation between ingesting arsenic-contaminated water and lung cancer. The group, led by Dr. Allan Smith, an emeritus professor at the UC Berkeley School of Public Health, and Dr. Craig Steinmaus studied cases of contaminated drinking water in Antofagasta, Chile, and in West Bengal. The group was the first to show respiratory health effects related to drinking arsenic, especially if the exposure is early in life. Their findings form the basis for the EPA’s stricter standard regarding arsenic.

“One thing that we’ve learned from our work in Chile is that even fairly remote exposures in childhood seem to increase risk for lung cancer,” Balmes says.

The team showed that in Antofagasta, arsenic exposure, especially during childhood, increased the risk of lung cancer compared with similar cities in Chile that didn’t have contaminated water. In their West Bengal study, the team showed drinking high levels of arsenic-contaminated water led to a greater risk of bronchiectasis, a rare respiratory disease.

“They’ve cleaned up the situation in Antofagasta, and they now have clean water, but there is still a lung cancer risk from the previous exposure,” Balmes says. “It’s kind of like asbestos that way. Asbestos also has a long latency with regard to certain kinds of cancers, meaning that exposures 40 years before diagnosis can be important. Arsenic exposure in childhood also seems to increase risk many years later.”

In California, 12 school districts serving over 5,000 students had arsenic levels that averaged from 30 percent higher to three times the federal limit, according to EIP. In Fresno County, the Lakeview Improvement Association, which serves 160 residents in Shaver Lake, had water with an average arsenic concentration of nearly nine times the federal limit. Some 16,000 soldiers at the U.S. Army Base Fort Irwin in San Bernardino County were found to live in facilities with tap water containing arsenic at 50 percent higher levels than the federal limit.

Officials from some of the water utilities cited in the study blamed the problem on bureaucratic obstacles, according to the report. Others indicated that failure to address the issue was a matter of time and money.

The EIP makes a series of recommendations for addressing the problem, including revising state regulations and guidance around warning people to stop drinking or cooking with water that fails to meet federal standards, and mailing public notices to consumers with information about options for treating contaminated water.

State data reveals that from 2011 to 2015, the average levels of arsenic in Kettleman City were 20 percent above the legal limit. The arsenic is naturally occurring, while decades of oil field operations have led to high levels of benzene pollution as well. The town is dependent on a state-funded program that supplies 30 gallons of bottled water per household per month.

Kettleman City has long been known as one of the most polluted places in California. All told, the community has multiple points of pollution exposure, including toxic water, pesticides from fields around town, poor air quality from thousands of diesel trucks passing by every day, and sewage sludge from Los Angeles that is dumped on the fields. The city is also home to the largest hazardous waste and PCB landfill in the western United States. Run by Chemical Waste Management (a subsidiary of Waste Management), the Kettleman Hills landfill has been a battleground of environmental justice issues for years.

Residents and activists are convinced that, whether cumulative from various sources or from a single source, environmental pollution is responsible for a rash of unusual birth defects, such as cleft palates and a number of infant deaths.

For Mares-Alatorre’s parents, Kettleman City was a refuge of sorts: They moved there from Los Angeles to get away from big city traffic and smog. Instead, they found water that regularly came out of the tap dark brown and mostly undrinkable.

In the late 1980s, her parents cofounded People for Clean Air and Water of Kettleman City (El Pueblo Para el Aire y Agua Limpia), a community environmental justice group to advocate on behalf of local residents. Today, Mares-Alatorre is one of its most vocal members.

“I kind of inherited the fight,” she says.

Poor rural communities using well water instead of a public water system are often the most affected by arsenic-contaminated water. While a municipal water system is able to test and filter out arsenic, people who get their water from individual wells usually aren’t able to do so, leaving them at risk.

“Many rural communities in the San Joaquin Valley have been found to have contaminated drinking water, and many of them are with arsenic,” says Bradley Angel, executive director of Greenaction for Health and Environmental Justice.

Greenaction and People for Clean Air and Water recently reached a landmark settlement in a civil rights complaint against the California Department of Toxic Substances Control and the California Environmental Protection Agency over the permit process involving the Kettleman Hills landfill. In 2014, DTSC approved a permit to expand the site over objections from Greenaction and People for Clean Air and Water. The groups filed federal and state civil rights complaints in March 2015 in response, claiming state agencies improperly approved the landfill expansion using a racially discriminatory process that granted permits even though they knew it would have a harmful impact on a community the state already admitted was vulnerable. At the time, the CalEnviroScreen tool had identified Kettleman City as being in the top 10 percent of environmentally vulnerable communities in the state. The DTSC approved the landfill expansion anyway.

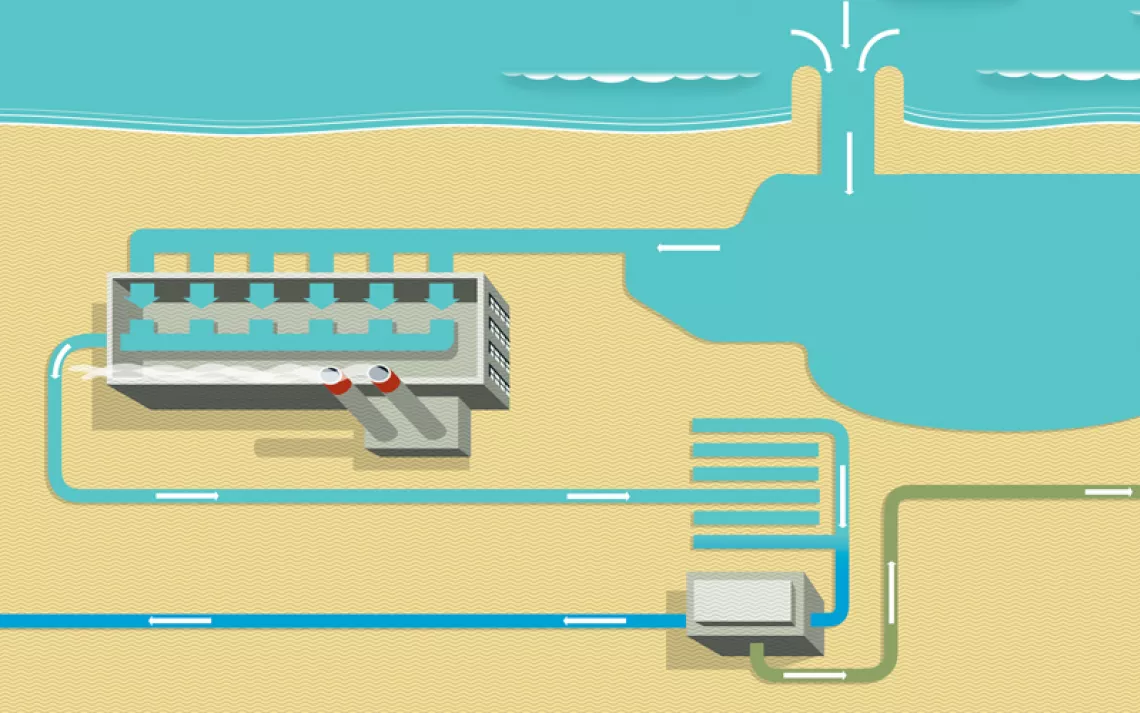

The complaint led to a settlement, announced on August 10, which explicitly requires the DTSC to consider the cumulative impacts of pollution on upcoming permitting decisions in Kettleman. The settlement has a provision requiring that the state not only keep the community informed, but also use its best efforts to expedite the implementation of a clean water project. Construction on the project is supposed to start in spring 2017.

“Kettleman City happens to be the picture postcard of environmental racism,” Angel says. “People of color are treated differently: They are more dumped on, more polluted, and more discriminated against in environmental decision-making, both by industry and government. It’s a pattern and practice of everything from indifference to negligence to outright racism, where the government doesn’t carry out their responsibility to provide clean drinking water for the people.”

The day after signing the civil rights agreement, Greenaction and People for Clean Air and Water received calls from the state water board asking for their help to organize a meeting about the water project and the status of the town’s water.

Ms. Mares-Alatorre says the timing wasn’t a coincidence. “We achieved that through the civil rights agreement.”

She said that the meeting, which occurred on August 31, included some positive developments. A school representative announced that filters had been installed on all school drinking fountains to reduce the level of arsenic in the water to safe levels. Also, the state announced its commitment to continue delivering bottled water.

“But,” she says, “when we asked them if there are filters on the bathroom sinks where they wash their hands, they said, ‘No, they don’t drink that water so it’s safe.’ Kids put that water over their face when they’re hot. It gets all over their fingers. They’re mistaken that kids are not still getting exposed.”

Angel has worked with diverse communities across the nation in almost 30 years of environmental justice work on a wide range of pollution and health issues. He says the community has been asking for clean water for decades, but it never happened—a trend he sees all too often.

“Typically, when the government issues a permit for some polluting facility and we challenge them, their response has always been, ‘Well, we followed our regulatory checklist, and we have to issue the permit.’ I always say, ‘You forgot to check off one box: complying with the law of the land. Specifically, civil rights law.’”

The Magazine of The Sierra Club

The Magazine of The Sierra Club