The Most Important Environmental Stories of 2016

A look back at this year’s headlines—and a glimpse of things to come

Photo by JaysonPhotography/iStock

|Christmas has come and gone. New Year’s is right around the corner. That must mean it’s time for my annual roundup of the most important environmental stories of the past year. Some of these topics got a ton of attention (cue: Trump, Standing Rock) while others didn’t get half as much as they deserved (think the Kigali HFC deal and a proposed delisting of the Yellowstone grizzlies). No matter how much ink and airtime they earned, all of these stories revealed some larger trend about the state of the environment and environmental advocacy.

Without further ado, here’s my list of the big, the bad, and the good from 2016.

1. Climate Science Denier-in-Chief

Photo by fleetingphoto/iStock Donald Trump’s stunning Electoral College victory over Hillary Clinton was the biggest story of 2016, period. American progressives were gutted by the upset, and have spent much of the time since figuring out how to resist the Trump-Pence administration.

Photo by fleetingphoto/iStock Donald Trump’s stunning Electoral College victory over Hillary Clinton was the biggest story of 2016, period. American progressives were gutted by the upset, and have spent much of the time since figuring out how to resist the Trump-Pence administration.

Many people reasonably fear that a Trump White House will threaten women’s reproductive rights, basic civil liberties, undocumented immigrants, the rule of law, and any hope of political discourse (and policy-making) rooted in, well, facts. Trump also poses a clear and present danger to our shared environment—especially the maintenance of a (more-or-less) stable climate.

Make no mistake: A Hillary Clinton presidency wouldn’t have been all rose petals and kumbaya for the environmental movement. At the very least, though, Clinton would have continued President Obama’s efforts to reduce greenhouse gas emissions. Now, we’re facing a climate science denier-in-chief, as Trump will hold the distinction of being the only head of state not to accept the basic science of human-driven global warming. Since the election, he has flirted with environmental luminaries like Al Gore and Leonardo DiCaprio, but his cabinet picks make plain he’s determined to stall, if not reverse, the United States’ recent progress on climate change. Scott Pruitt—a longtime oil and gas industry bagman and fellow climate change denier—has been chosen to lead the EPA. The CEO of ExxonMobil has been nominated for secretary of state. The Clean Power Plan will face attacks from within the federal government beginning on day one of Trump’s presidency. In the face of the coming onslaught, environmental leaders say they are ready to fight like hell to preserve clean air, clean water, a stable climate, and the integrity of public lands and wildlife protections. Expect four long, tough years of political battles to maintain a healthy environment.

2. The Standoff at Standing Rock

Photo by Brian Nevins When LaDonna Brave Bull Allard, a member of North Dakota’s Standing Rock Sioux nation, set up an encampment near the Missouri River in April to draw attention to a planned petroleum conduit, hardly anyone had heard of the Dakota Access Pipeline. By September, the resistance camp of “water protectors” had grown to include thousands of people, and the standoff between indigenous and environmental activists and Energy Transfer Partners and North Dakota law enforcement had catapulted into the national headlines. Scenes from the weeks of rolling conflicts—women set upon by attack dogs, people arrested in the midst of prayer, sound cannons targeted at marchers and their horses, heavy equipment lit on fire—galvanized public sympathy for the Native American-led resistance. Solidarity caravans and resupply convoys poured into the water protectors’ camps throughout the fall. Then the water protectors’ (provisional) victories sparked new hope for the power of grassroots activism. In early September, the Obama administration halted pipeline construction at the Missouri River, and in a sweeping statement said the controversy should prompt “a serious discussion on whether there should be a nationwide reform with respect to considering tribes’ views on these types of infrastructure projects.” On December 4, Obama called on the Army Corps of Engineers to look for a different pipeline route.

Photo by Brian Nevins When LaDonna Brave Bull Allard, a member of North Dakota’s Standing Rock Sioux nation, set up an encampment near the Missouri River in April to draw attention to a planned petroleum conduit, hardly anyone had heard of the Dakota Access Pipeline. By September, the resistance camp of “water protectors” had grown to include thousands of people, and the standoff between indigenous and environmental activists and Energy Transfer Partners and North Dakota law enforcement had catapulted into the national headlines. Scenes from the weeks of rolling conflicts—women set upon by attack dogs, people arrested in the midst of prayer, sound cannons targeted at marchers and their horses, heavy equipment lit on fire—galvanized public sympathy for the Native American-led resistance. Solidarity caravans and resupply convoys poured into the water protectors’ camps throughout the fall. Then the water protectors’ (provisional) victories sparked new hope for the power of grassroots activism. In early September, the Obama administration halted pipeline construction at the Missouri River, and in a sweeping statement said the controversy should prompt “a serious discussion on whether there should be a nationwide reform with respect to considering tribes’ views on these types of infrastructure projects.” On December 4, Obama called on the Army Corps of Engineers to look for a different pipeline route.

The battle over the Dakota Access Pipeline is huge for two reasons.

First, it made visible the strength and sophistication of a resurgent Native sovereignty movement. This movement has been building for years. As I wrote in an article for The American Prospect, “From the Coast Salish nations of the Pacific Northwest, to the Ojibwe lands around the Great Lakes, to the Iroquois territory of New York, a new fighting spirit is sweeping across Indian Country.” The mediagenic images from the banks of the Missouri River put that spirit front and center of (non-Native) Americans’ attention. Environmental organizations have long sought to create alliances with indigenous peoples, with whom they share a similar worldview about how humanity should treat the planet’s lands and waters. The fight against the Keystone XL pipeline was a good example. Now environmental groups are taking leadership from Native Americans. And just in time. When it comes to disputes over resource extraction and environmental protection, Native Americans’ moral authority can supply a countervailing force to the ethic of greed and corruption that will likely emanate from a gilded Oval Office.

Second, the #NoDAPL movement offers a template for resistance in the Age of Trump. We know what to expect from a new resource rush: attempts to put in place more fracking wells, more pipelines, more oil trains, more gas terminals, more clear-cutting, more mining. And with the Standing Rock experience fresh in our minds, we also know how to oppose that resource rush: with blockades, marches, petitions, and prayer in the face of violence. The water protectors showed the power and force of putting bodies on the line to keep oil and gas and coal in the ground.

3. Fires and Floods

Photo by Mike Daniels We did it again! According to the World Meteorological Organization, 2016 will be the hottest year in history, breaking the record set in . . . well, set just a year ago. Meteorologists project that average global temperatures in 2016 will be 1.2 degrees Celsius above preindustrial levels.

Photo by Mike Daniels We did it again! According to the World Meteorological Organization, 2016 will be the hottest year in history, breaking the record set in . . . well, set just a year ago. Meteorologists project that average global temperatures in 2016 will be 1.2 degrees Celsius above preindustrial levels.

Though it’s difficult to peg any single freak weather occurrence to global warming (obligatory environmental journalist caveat), it’s not hard to spot signs that things are amiss. A couple of big phenomena grabbed headlines.

First, in May a wildfire of unprecedented size and ferocity swept through the boreal forests around Fort McMurray, Alberta. The fires—which burned some 1.5 million acres, destroyed 2,400 buildings, and forced the evacuation of nearly the entire community—were fueled by freakishly dry and warm weather. While fire is a natural part of forest ecosystems, the fires grew out of control due to record high temperatures—as high as 91 degrees F, in May, in far northern Alberta. At least we can say this for Mother Nature: She has a sense of irony. Fort McMurray, you may recall, is the boom town at the center of the tar sands industry.

After the fires came floods. In August, extreme rains brought biblical-scale flooding to southern Louisiana. In Livingston Parish, 31 inches of rain fell in just 15 hours. The floods drove tens of thousands from their homes, caused some $30 million in damage, and contributed to the deaths of at least 13 people. The Red Cross said it was the worst natural disaster to hit the United States since Hurricane Sandy in 2012.

Speaking of disaster, I’d be remiss not to include this other downer: In April, oceanographers reported that, due to an influx of warmer and more acidic seawater, 93 percent of Australia’s Great Barrier Reef is suffering from coral bleaching. While it may be too early to write the reef’s obituary, there’s no doubt that the ecosystem is in dire straits. Here’s how researcher Terry Hughes, writing on Twitter, described reaction to his findings: “I showed the results of aerial surveys of #bleaching on the #GreatBarrierReef to my students. And then we wept.”

4. Kigali + Paris = Progress on Climate

Photo by Epitavi/iStock But not all hope is lost. Even as climate change becomes more evident, global leaders continue to take steps to address the crisis. Two important climate mitigation developments happened this year.

Photo by Epitavi/iStock But not all hope is lost. Even as climate change becomes more evident, global leaders continue to take steps to address the crisis. Two important climate mitigation developments happened this year.

The first one was something of a sleeper story. In October, negotiators from 170 countries meeting in Kigali, Rwanda, agreed to a binding agreement to phase out the use of hydrofluorocarbons, or HFCs. What’s an HFC?, you might be asking (especially since the agreement got little media attention). Basically, HFCs are the primary component of air conditioning. While AC is a great thing to have while the planet gets hotter, HFCS are, unfortunately, a powerful heat-trapping gas—about 1,000 times more potent than carbon dioxide. So this is a big deal, one that will, as it goes into effect, avoid the equivalent of 70 billion tons of CO2. Also—and this is crucial—unlike the Paris Agreement, the Kigali deal is legally binding.

And what about the Paris Agreement? On November 3, it officially went into effect. To be sure, the great weakness of the (otherwise landmark) Paris Agreement is that its greenhouse gas reduction targets are voluntary. Nevertheless, the major signatories say they are committed to fulfilling their obligations—and they reaffirmed those commitments at a November UN meeting in Marrakesh, Morocco, even as news of the Trump victory sunk in. “It is global society’s will that all want to cooperate to combat climate change,” a senior Chinese negotiator said in Marrakesh, adding that “any movement by the new U.S. government” won’t distract China from its move toward a renewable energy economy.

Perhaps the most important post-U.S. election climate change news has been the firm statements by major emitters like China and India that they plan to continue their transition toward a clean energy economy. The transition appears inexorable due to the falling price of renewables, a fact that offers an important lesson to Donald Trump, should he care to heed it: The clearest path for reviving American manufacturing lies in making investments in clean energy; a failure to make those investments will leave the Unite States scrambling to catch up.

5. Monument Man

Photo by zrfphoto/iStock Since the election, the Obama White House has been racing to do everything it can in terms of environmental protection in advance of Trump taking office. But even before the election results came in, the president knew that his environmental legacy would rest on what he could do with executive actions—and few executive actions are bolder than the creation of national monuments.

Photo by zrfphoto/iStock Since the election, the Obama White House has been racing to do everything it can in terms of environmental protection in advance of Trump taking office. But even before the election results came in, the president knew that his environmental legacy would rest on what he could do with executive actions—and few executive actions are bolder than the creation of national monuments.

As if making up for lost time, in 2016 Obama used his powers under the Antiquities Act to protect millions of acres of lands and waters. In February, the president established three new national monuments in the California desert that, combined with existing monuments and national parks, knit together a vast wildlands corridor. To mark the centennial of the establishment of the National Park Service (another big conservation story this year), Obama created the Katahdin Woods and Waters National Monument in Maine. Less than a month later, he established the first marine monument in the Atlantic Ocean. Obama continued his drive for marine protection in December, when he banned offshore oil and gas drilling in the Arctic Ocean and part of the Atlantic.

Altogether, Obama has used the Antiquities Act more than any of his predecessors, and in the process has protected nearly 4 million acres. Those protections are permanent. While the Trump administration will be able to roll back some of Obama’s other environmental accomplishments, there is no precedent for abolishing a national monument once it has been created.

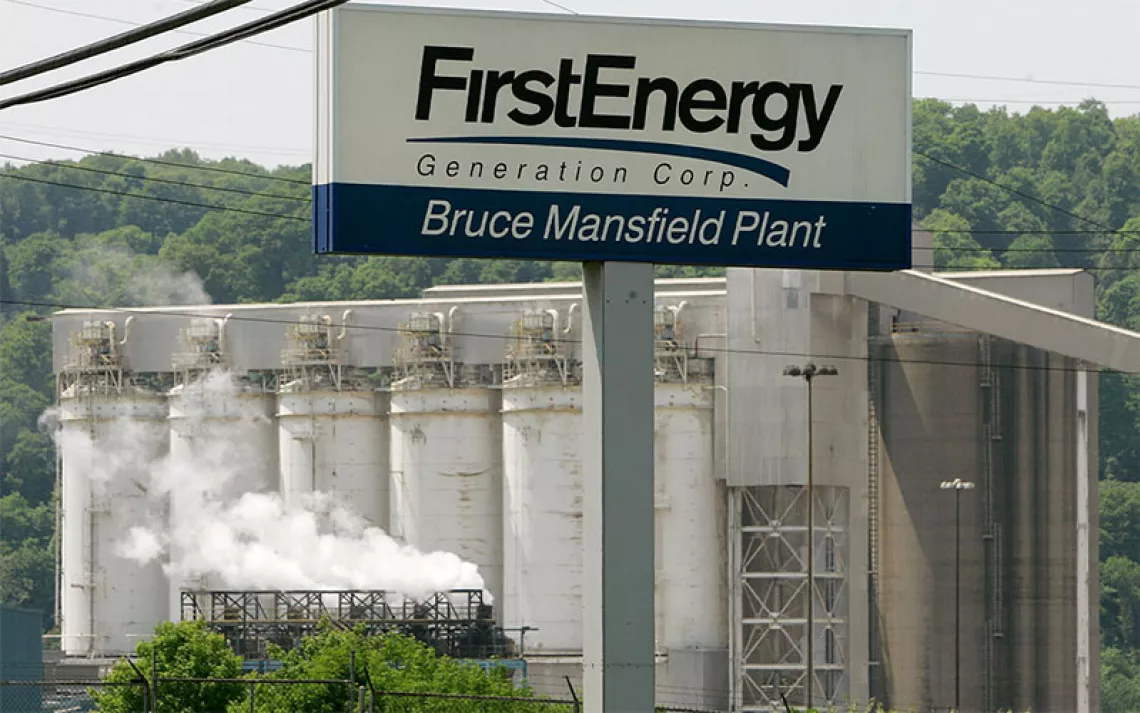

6. Big Coal Goes Bankrupt

Photo by DmyTo/iStock On the morning after the U.S. elections, coal mining corporation Peabody Energy’s stock price jumped 50 percent as investors assumed that a Trump administration would be a friend of the coal industry. It was more of a blip than a market correction. Earlier this year, in April, Peabody had filed for bankruptcy. The company’s move to seek protection from its creditors was just the latest in a string of coal industry bankruptcies: Arch Coal, Alpha Natural Resources, and Patriot Coal have also filed for Chapter 11.

Photo by DmyTo/iStock On the morning after the U.S. elections, coal mining corporation Peabody Energy’s stock price jumped 50 percent as investors assumed that a Trump administration would be a friend of the coal industry. It was more of a blip than a market correction. Earlier this year, in April, Peabody had filed for bankruptcy. The company’s move to seek protection from its creditors was just the latest in a string of coal industry bankruptcies: Arch Coal, Alpha Natural Resources, and Patriot Coal have also filed for Chapter 11.

While campaigning in coal country, Trump pledged that he was going to put coal miners back to work. It’s a false promise. There is little Trump can do to reverse the steady demise of the industry. A combination of factors—an overabundance of cheap gas, the plummeting price of renewables like solar and wind, and a determined grassroots effort (led by the Sierra Club’s Beyond Coal campaign) to halt proposed coal plants and shut down existing ones—has turned the industry into what one market analyst has called a “dead man walking.”

The economics simply don’t add up for the coal industry. State-regulated utilities have a legal mandate to provide their customers with the cheapest rates possible, and in many places coal no longer meets that requirement. The cost of installed solar is 1/150th of what it was in the 1970s, and wind continues to get cheaper, too. Wind accounts for about 40 percent of new installed capacity; in December America’s first offshore wind farm went online. No wonder even staunch coal ally Senator Mitch McConnell of Kentucky has sought to dampen expectations of a coal industry revival.

All of which presents a major challenge to the incoming administration. Will Trump have the courage and the candor to tell his supporters in coal country that they best prepare a Plan B? Will he and a GOP-dominated Congress make the kind of public investments that can soften the blow? Coal’s demise is also a test for the American environmental movement. Greens will have to do a much better job of reaching out to coal workers and creating alliances to push for policies that ensure a clean energy economy will work for all.

7. California Shows What’s Possible

Illustration by tkacchuk/iStock If you need evidence that it’s possible to grow an economy and create jobs while also tackling greenhouse gas emissions, you don’t have to look any further than California.

Illustration by tkacchuk/iStock If you need evidence that it’s possible to grow an economy and create jobs while also tackling greenhouse gas emissions, you don’t have to look any further than California.

Mid-year economic statistics released in July showed that the Golden State’s economy grew 2.9 percent from 2015 to 2016 and added close to a half million new jobs. Compared to a national economic growth rate of 1.7 percent, it’s clear that California’s economy is not only big, but it’s booming, too.

(The economies shrank in the fossil-fuel-producing states of North Dakota, with a 6.7 percent decline, and Wyoming, with a 2.9 percent decline. Evidence of a resource-curse, anyone?)

Here’s the important thing: California’s gangbusters growth has occurred even though the state has some of the strictest energy efficiency requirements and pollution controls in the country. Per capita electricity usage has been essentially flat for the past 40 years. In 2016, state leaders doubled down on their commitment to the environment when the legislature passed, and Governor Jerry Brown signed, a bill that requires the state to cut greenhouse gas emissions to 40 percent below 1990 levels by 2030.

California has the world’s sixth-largest economy (bigger than that of France and Brazil), and its success in balancing carbon pollution controls and economic growth is part of an encouraging global trend: The decoupling of growth and greenhouse gas emissions. For two years in a row now, according to the International Energy Agency, human-made greenhouse gases have stayed flat even as the global economy has increased in size.

The takeaway? Economic prosperity today doesn’t require mortgaging the climate of tomorrow.

8. Berta Cáceres Assassinated

Photo by Chixoy Environmentalists around the world were horrified when, in early March, Honduran environmental leader Berta Cáceres was murdered in her home. Cáceres—a mother of four who was assassinated on the eve of her 45th birthday—was a cofounder of the Council of Popular Indigenous Organizations of Honduras, a group that has spearheaded opposition against a mega-dam project in the Gualcarque river basin. That resistance earned Cáceres enemies within the Honduran political and economic elite; in a country with an awful record of political violence and impunity, those enemies felt free to destroy her.

Photo by Chixoy Environmentalists around the world were horrified when, in early March, Honduran environmental leader Berta Cáceres was murdered in her home. Cáceres—a mother of four who was assassinated on the eve of her 45th birthday—was a cofounder of the Council of Popular Indigenous Organizations of Honduras, a group that has spearheaded opposition against a mega-dam project in the Gualcarque river basin. That resistance earned Cáceres enemies within the Honduran political and economic elite; in a country with an awful record of political violence and impunity, those enemies felt free to destroy her.

Cáceres’s murder earned international attention in part because she already enjoyed a global reputation, having won the Goldman Environmental Prize just the year before. Sadly, though, such political assassinations are all too common. According to a June 2016 report by Global Witness, murders of environmental activists are at a record high. At least 185 environmental activists were killed in 2015, a 60 percent jump from the previous year. “As demand for products like minerals, timber, and palm oil continues, governments, companies and criminal gangs are seizing land in defiance of the people who live on it,” Billy Kyte, a senior campaigner for Global Witness and author of the report, told the Guardian. “Communities that take a stand are increasingly finding themselves in the firing line of companies’ private security, state forces, and a thriving market for contract killers.”

For American environmentalists, the chronic killings of activists in other nations pose a test of our solidarity and our commitment to our cause. Most of the time our advocacy is painless and risk-free. If that’s the case, maybe it’s time for us to raise the stakes.

9. Flint Water Crisis

Photo by svedoliver/iStock 2016 wasn’t a week old yet when Michigan governor Rick Snyder declared a state of emergency for Genesee County in response to revelations that the water supply for the city of Flint contained dangerous levels of lead.

Photo by svedoliver/iStock 2016 wasn’t a week old yet when Michigan governor Rick Snyder declared a state of emergency for Genesee County in response to revelations that the water supply for the city of Flint contained dangerous levels of lead.

By mid-January, the national guard had been mobilized to deliver water supplies to Flint residents, and the city—already an emblem of Rust Belt desperation since Michael Moore’s breakout documentary Roger and Me—had become a symbol of structural environmental racism.

Flint is notoriously poor (more than 41 percent of residents live below the poverty line) and primarily black (56 percent of the population is African American), and it wasn’t difficult to draw a connection between those facts and the official neglect the community has suffered. The city’s water system had been a mess for years (there were repeated water contaminations of fecal coliform bacteria). As early as February 2015, the EPA warned Michigan’s Department of Environmental Quality about lead contamination in the water. Yet state officials continued to dither even as city residents became increasingly vocal with their concerns about water quality. By the time officials acknowledged the scale of the problem, thousands of people, including vulnerable children, had been exposed to lead poisoning, and a dozen people had died of Legionnaires disease.

Some people are finally being held accountable for this man-made disaster; investigators have filed criminal charges against 13 current and former state and local officials. Nevertheless, the water crisis in Flint could serve as a parable for many of the dysfunctions in the United States today. It’s evidence of the persistence of racism, the short-sightedness of austerity policies, and the neglect shown to poor communities when it comes to public health. It’s also one more example of how by investing in repairs and upgrades to our infrastructure, we can create on-ramps to prosperity (are you seeing a trend here?).

If Donald Trump is truly committed to “making America great again,” here’s an idea: Let’s start with overhauling the water systems in Flint and the other communities in the United States beset by dangerous water. At the very least, we should be able to provide our citizens with the basic human right to clean, potable water.

10. Bad News for the Bears

Photo by JaysonPhotography/iStock I’ll admit that this last story didn’t get all that much national attention, but it’s an important one in that it could be a glimpse of things to come in 2017. In March, the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service announced its intention to remove grizzly bears in the Greater Yellowstone Ecosystem from protection under the Endangered Species Act. While the feds—supported by state officials in Montana, Wyoming, and Idaho who are eager to resume trophy hunting—say the bear’s numbers are sufficiently recovered, conservation organizations have pushed back. Conservationists argue that the grizzlies remain at a fraction of their historic numbers and that they are at risk of a genetic bottleneck since the GYE population is disconnected from populations to the north. At a series of public listening sessions that took place this summer throughout the northern Rockies, emotions ran high as wildlife lovers sought to defend the bears against hunters eager to stalk them again.

Photo by JaysonPhotography/iStock I’ll admit that this last story didn’t get all that much national attention, but it’s an important one in that it could be a glimpse of things to come in 2017. In March, the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service announced its intention to remove grizzly bears in the Greater Yellowstone Ecosystem from protection under the Endangered Species Act. While the feds—supported by state officials in Montana, Wyoming, and Idaho who are eager to resume trophy hunting—say the bear’s numbers are sufficiently recovered, conservation organizations have pushed back. Conservationists argue that the grizzlies remain at a fraction of their historic numbers and that they are at risk of a genetic bottleneck since the GYE population is disconnected from populations to the north. At a series of public listening sessions that took place this summer throughout the northern Rockies, emotions ran high as wildlife lovers sought to defend the bears against hunters eager to stalk them again.

At this point, the Obama administration has punted the decision to its successors—and that’s bad news for the bears. The 2015 Christmas card of Montana congressman Ryan Zinke, Trump’s pick for secretary of the interior, featured a dead wolf slung across Santa’s sleigh—an indication, of a sort, about Zinke’s feelings toward predators and perhaps wildlife more generally. It seems likely that the Yellowstone area bears will lose ESA protection, and that other animals will find themselves under threat, too. Conservationists worry that an Interior Department under Zinke will try to delist the wolf populations in the Great Lakes and will undo Secretary Sally Jewell’s efforts to protect the greater sage grouse.

All of which has me, even in this holiday season, about as ornery as a grizzly bear in a trap.

The Magazine of The Sierra Club

The Magazine of The Sierra Club