Climate Treaty Signatories Gather in Marrakesh for “COP of Action” in the Global Fight Against Climate Change

Push to decarbonize economies while promoting equity among nations will be central as conference gets underway

Photo by Epitavi/iStock

The governing body of the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC) opened its 22nd session in Marrakesh today as diplomats from across the world gathered to respond to the global climate crisis. It is the first meeting of the Conference of the Parties (COP) since the landmark Paris Climate Agreement was reached at last year’s COP21 meeting in France. The agreement, which is currently ratified by 100 nations and counting, including the United States, entered into force on Friday.

After decades of unchecked global greenhouse gas emissions even as international negotiations inched forward, the Paris Agreement represents a watershed moment for the struggle to avoid a climate change point of no return. According to some experts, that threshold may have already been breached, with new research showing substantial melting beneath the Antarctic ice shelves.

COP22 begins just days after the United Nations Environment Program (UNEP) released its annual Emissions Gap Report, which included a stark warning that not enough was being done to keep the world on track toward achieving the temperature reductions targets set by the Paris Agreement. The UNEP stated that even with the Paris Agreement, global temperatures will rise between 2.9 and 3.4 degrees Celsius. Just a degree increase in temperature can lead to more destructive weather events like floods and wildfires, sea level rise from melting glaciers, and extreme drought.

But unlike other landmark climate protocols reached since 1994, when the UNFCCC entered into force, the Paris Agreement is significant for the speed with which nations have ratified it and pushed for implementation.

“It’s unprecedented to see an agreement like this enter into force so quickly, in less than a year and ahead of the Marrakesh meeting,” said Rachel Cleetus, lead economist and climate policy manager at the Union of Concerned Scientists. “It really signals a strong continued commitment from countries since Paris. There was a snowball affect as nations like the United States joined early.”

A number of other major climate change agreements have already been finalized since the COP21 meeting in Paris. A legally binding deal agreed to in Kigali, Rwanda, last month by 170 countries will cut the use of hydrofluorocarbons, or HFCs, used in air conditioners and refrigerators. Also in October, national governments reached an agreement on capping aircraft carbon emissions beginning in 2020.

The COP21 agreement produced ambitious commitments to mitigate the most devastating impacts of climate change, including long-term goals to decarbonize industrial economies, initiatives for a more renewable energy sector, and a target of limiting global temperature rise below 2 degrees Celsius (3.6 degrees Fahrenheit) above preindustrial levels. It also included a commitment to pursue a more ambitious 1.5 degree limit. Few believe the 2 degrees Celsius target would be enough to mitigate the most devastating impacts of climate change, especially for island nations that are already seeing a rising sea level.

The COP22 in Marrakesh will focus on establishing the timeline, rules, and processes for delivering on those commitments.

Dr. Jonathan Pershing, special envoy for climate change at the U.S. Department of State, said that the discussions in Marrakesh would focus on the details of negotiations for implementing the framework from Paris, including guidelines for transparency and the rules for how countries will report on their progress in meeting key benchmarks.

“If we take a look back at our domestic circumstances, flooding in Florida is a real consequence of climate change,” Pershing told reporters in a press briefing. “The issues around Superstorm Sandy and the flooding of New York subways is a climate change issue. If we think about the increasing drought in the American Southwest, probabilities have increased substantially because of climate change.”

What differentiates the Paris Agreement from previous protocols, according to Pershing, is the holistic involvement of all nations producing individual agendas to reduce emissions. “It’s built from the national circumstances and national decisions of countries,” Pershing said. “It’s not a top-down negotiation where the globe decided internationally about what each country should do. Each country put forward its own development plan in the context of aggressive efforts to reduce emissions.”

Rachel Cleetus said the COP22 will concentrate on developing “the rule book for Paris.” “How are we going to actually deliver? How are countries going to continue to maintain the trust that we’ve built? That trust is going to come both from countries moving forward with domestic policies that meet the kinds of commitments they’ve made and some processes to help verify and create transparency, around not just mitigation commitments but also finance. So I would say in Marrakesh, it’s not glamorous Paris. It’s where you roll up your sleeves and start talking about the details.”

The Marrakesh sessions will also feature planning meetings to contribute outlines and ideas for a special report the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) intends to deliver in 2018 on the impacts of temperatures rising 1.5 degrees and emission pathways that will help limit global temperature increase. The Paris Agreement has a mechanism for increasing its emissions reductions targets over time, and the IPCC report is expected to have an impact on those discussions.

In the second week of COP22, the United States is expected to share a sweeping long-term plan to decarbonize its economy by 2050. The United States is filing its plan early, which has generated optimism that the world’s second largest emitter of greenhouse gases (after China) will present an ambitious, comprehensive plan identifying technology pathways that other countries can for moving toward a net zero economy.

COP22 sessions will deal with issues that did not get resolved in Paris: in particular, the unfinished business around equity among nations, and the thornier issue of climate finance, or climate compensation. Developing countries are waiting to hear about whether they will be compensated for the climate dislocations to which developed countries have contributed during decades of industrialization. Poorer nations are also expecting to hear about financing mechanisms that will help them transition to a low-carbon economy while responding to significant climate impacts already underway.

COP22 opens one day before the election of a new U.S. president, following a campaign season notable for the near total absence of climate change as a topic of public debate. But while Donald Trump has vowed he will withdraw the United States from the Paris Agreement if elected, John Morton, director for energy and climate change for the National Security Council, says the global effort to achieve the agreement’s goals is moving forward regardless of the election’s outcome.

“What we have seen in recent months and years is a recognized, now inevitability of the transition to a low-carbon economy,” Morton said. “The international business community, the international policy community, is moving forward, and will continue to move forward. The question of commitment to action is no longer one which is being debated. It’s a question of how quickly it will move forward, and frankly, who will lead and will benefit most, from this transition to a lower-carbon economy.”

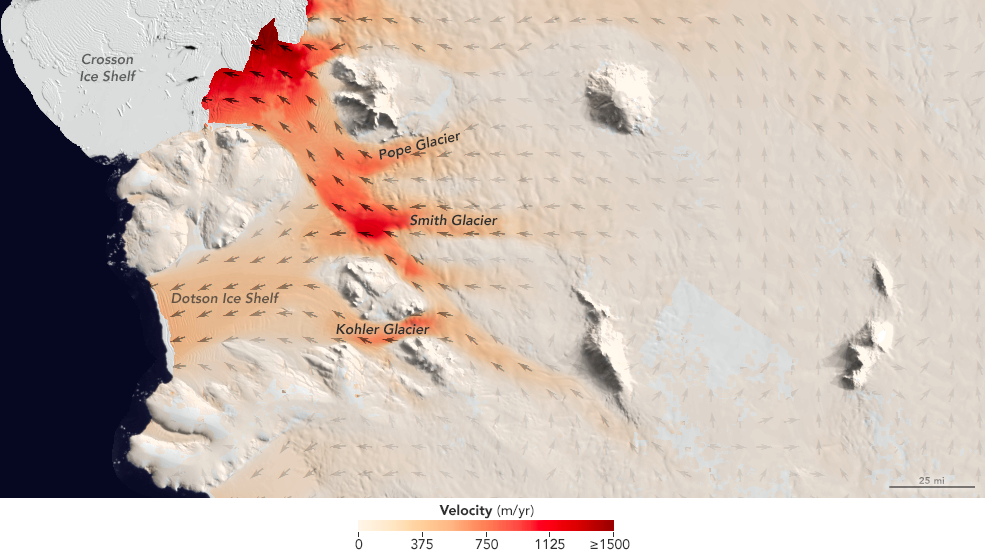

The COP22 meetings come at a time when new research has detected accelerating melting rates in west Antarctica. Researchers at the University of California at Irvine and NASA analyzed two ice shelves and three glaciers that feed them in the Amundsen Sea Embankment region. The researchers found evidence of continued retreat of the grounding line of two of the three glaciers—the line at which the ice starts floating. The largest rate of retreat was seen with the Smith glacier. The study produced new evidence of ice melting at the bottom of the glaciers.

“The grounding line retreat is happening pretty much in all areas of the region,” said Dr. Bernd Scheuchl, lead scientist for the study and associate project scientist at the Department of Earth System Science at UCI. “There’s significant potential that this retreat will continue for some time to come. More ice is melting and being transported into the ocean than is being reproduced through snowfall, meaning that this ice being lost will contribute to sea level rise.”

Photo courtesy of the University of California, Irvine

Dr. Scheuchl did additional background research on how areas in the United States will be impacted. For example, Huntington Beach, California, would be severely affected by a one-meter sea level rise by 2100, including severe coastal flooding. He also points out that the United States military is currently present in 156 nations, and there are 95,471 miles of coastline along which 1,774 U.S. military sites reside across the globe. Such sites face significant risk from rising sea levels. “The armed forces is considering what impact global sea level rise will have on their bases and the sites they are using worldwide,” he says.

While experts acknowledge that climate change is no longer a phenomenon that can be averted, most agree it’s not too late to slow it down. The Paris Agreement is a bold step in that direction as nations around the world have demonstrated unprecedented unity, and urgency, around the need to take action.

“The obstacle we face is not technology or feasibility. The obstacle we face is political will,” Rachel Cleetus said. “The only way we change that is if a lot of people everywhere raise their voices and put pressure on their policymakers to make this a priority. Paris showed us that it is possible for nations to rise above their narrow self-interest to see the greater common good. We just need to continue that momentum, and that doesn’t happen in a vacuum. It happens if people get engaged, if people add their voices, if people continue to put pressure on their policymakers.”

The Magazine of The Sierra Club

The Magazine of The Sierra Club