Earth’s Annual Average Temperatures Set to Breach 1.5°C for the First Time

The grave reality of a do-little-on-climate scenario is becoming clear

People watch the sunset from a peak at Papago Park in Phoenix, Arizona. | Photo by Charlie Riedel/AP File

Perhaps no other benchmark for climate action is as sacrosanct as limiting global warming to 1.5°C, or 2.7°F. In 2015, the world’s governments codified the 1.5°C goal in the Paris Agreement as crucial to avoiding the worst impacts from a changing climate. The world must hold average global temperatures “well below 2°C,” the countries that adopted the agreement stated at the time. Crossing the 1.5°C threshold would risk “unleashing far more severe climate change impacts, including more frequent and severe droughts, heat waves, and rainfall.”

Since then, the movement to “keep 1.5°C alive” has united everyone from youth organizers to climate envoys to corporate sustainability officers. Popular campaigns and climate commitments like “net zero by 2050” are based on meeting this commitment. Sultan al-Jaber, the president of the upcoming COP28 climate summit scheduled to take place in November in Dubai, has said that he has “no intention whatsoever of deviating from the 1.5° goal” during the summit and that “keeping 1.5° alive is a top priority.” And today in New York City, United Nations Secretary-General António Guterres convenes a Climate Ambition Summit to lift up that goal and compel industrial nations to commit to solutions that keep it actionable. “The world needs immediate and deep reductions in emissions now, and over the course of the next three decades, to limit global warming to 1.5 degrees above pre-industrial levels and prevent the worst impacts,” the UN summit organizers have declared.

But a scientific consensus is growing that annual global temperatures are set to breach 1.5°C for the first time perhaps even as early as this year. If that happens, it could be a signal that—due to the failure of industrial societies to systematically transform everything from food and energy to transportation systems, much of which are still powered by fossil fuels—the 1.5°C goal is at risk of falling out of reach, with grave implications for the efforts to rein in global warming’s worst impacts.

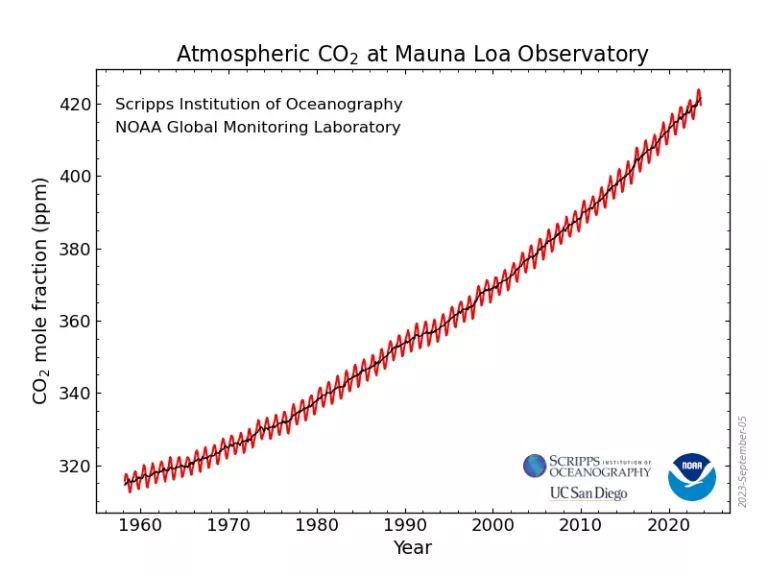

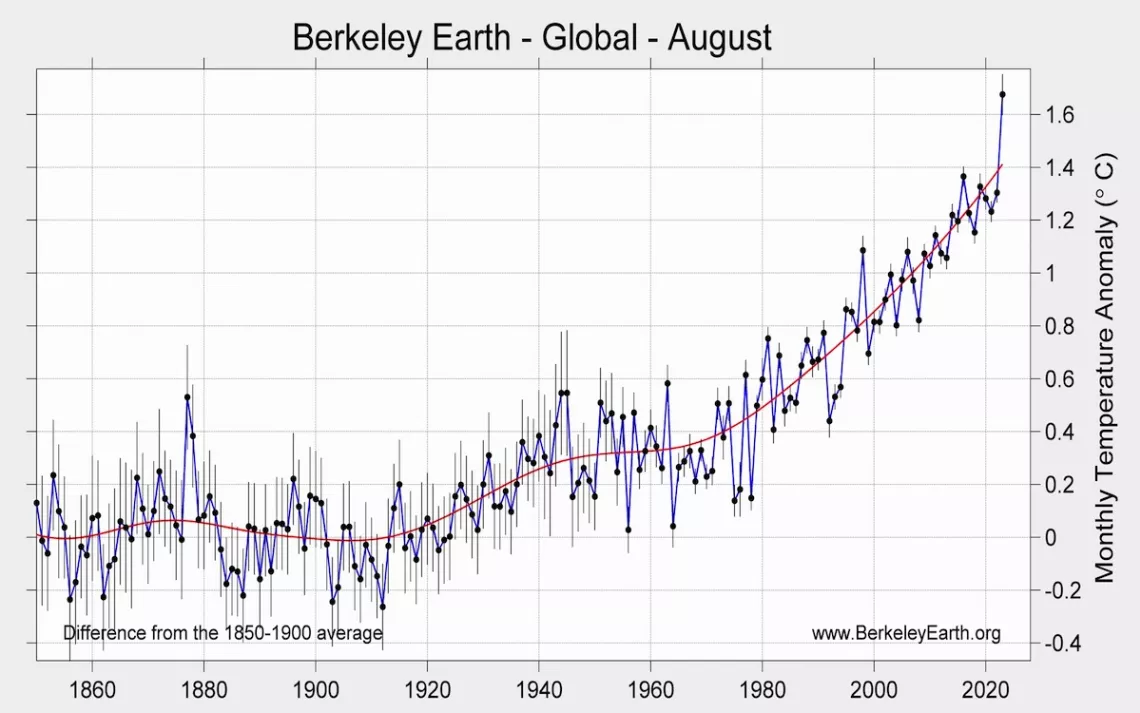

According to Berkeley Earth, the planet is currently 1.3°C (or about 2.3°F) hotter on average annually than it was before the Industrial Revolution, a temperature increase that squarely tracks with the expanding use of fossil fuels for energy during that time. There is currently more carbon in the atmosphere than there has been in over 3 million years. In the last 200 years alone, human activity has increased the carbon in the atmosphere from 280 parts per million to about 418 ppm—a rate and scale of human impact on global concentrations of greenhouse gases that is unprecedented. Ecosystems and the living species that depend on them, ours included, were not designed to adapt to such an accelerating pace of change to our climate.

Data by NOAA, measured at Mauna Loa Observatory, Hawai'i.

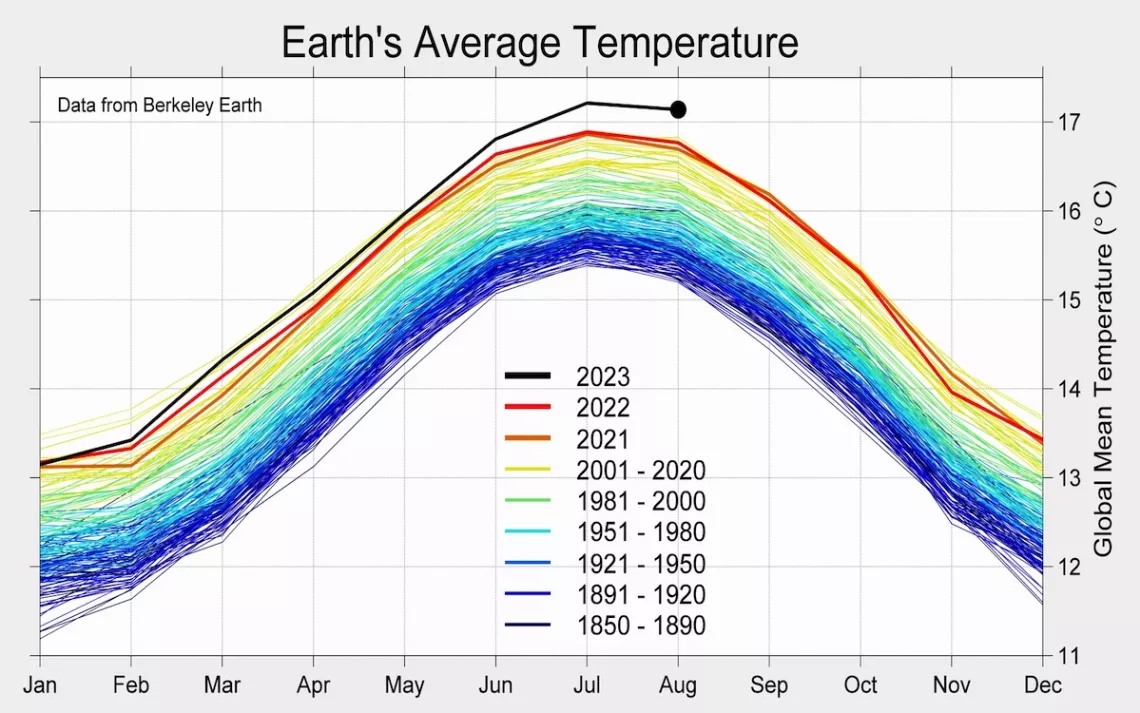

Data by Berkeley Earth

Already in a 1.3°C world, the impacts of warming have been global, costly, and in many cases, deadly. This year incidents of extreme wildfire and heat waves, flooding, drought, sea level rise, and desertification have smashed records. At one point this summer, half of all residents living in the United States were under an extreme heat warning. Over 5,000 wildfires burned in Canada so far this year alone, scorching over 37 million acres and dumping plumes of toxic smoke across North America. This year’s record-setting summer delivered the hottest temperatures in 125,000 years. Ocean temperatures have shattered records this year, reaching levels not seen in over 170 years. The National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) reported that Antarctica saw its third consecutive month of record-low sea ice.

And the costs of this warming are rising. In a report this month, NOAA confirmed a total of 23 separate billion-dollar weather and climate disasters this year—“the most events on record during a calendar year.”

“The phrase the new normal drives me a little bit nuts because to me that implies these are conditions we can get used to and can expect,” says Andrew Pershing, VP for science at Climate Central. “The reality is we can’t get used to these conditions. Next year, the pressure on us from climate change is going to be even stronger, and the year after that even stronger. We can’t adjust to the conditions we’ve observed. We have to anticipate where the ball is going and try to be ready for these future summers that are going to be even warmer.”

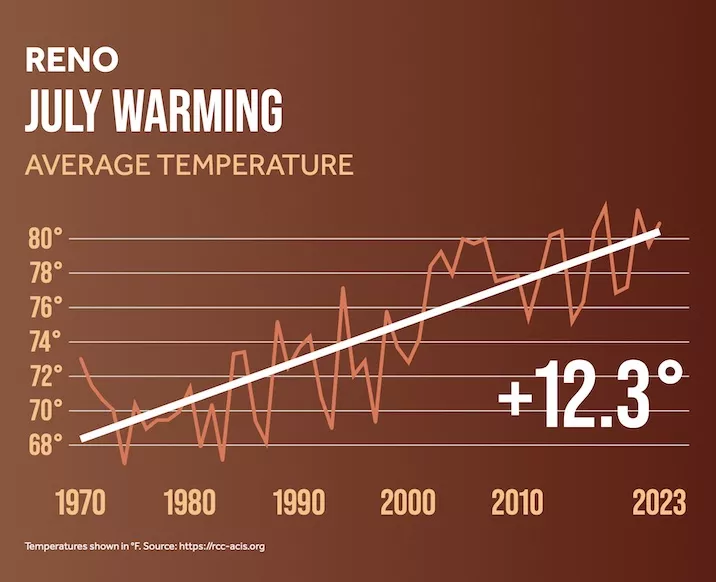

Climate Central tracks warming trends in approximately 200 cities with data going back to 1970. In San Francisco, average temperatures have risen by just 2.8°F since 1970. In Phoenix, which this past July suffered over 30 straight days of temperatures exceeding 110°F, the city’s average temperatures have increased by 3.6°F since 1970. In Reno, annual temperatures have increased on average by a whopping 12.3°F since 1970. Earlier this month, using analyses from its Climate Shift Index, Climate Central revealed that climate change increased temperatures this summer for nearly every human being on the planet.

Data by Climate Central

A world with a long-term annual average increase of 1.5°C of warming is virtually certain to see multiple and compounding climate shocks, with devastating extreme heat, drought, flooding, and arctic melting. Climate models still offer scenarios in which we could limit long-term average global temperatures to 1.5°C. But industrial societies would have to start reducing emissions immediately and force them down to zero by 2040 in order to avoid a 1.5°C world.

That’s not happening. In spite of accelerating investment in renewable energy sources such as wind and solar, fossil fuels still provide approximately 80 percent of the world’s energy. This “business as usual” reality of using fossil fuels for energy is the background to a growing consensus that the planet will breach the 1.5°C threshold soon.

“The growing consensus in the field is that we are headed to an overshoot world."

According to analysts at Berkeley Earth, there is a roughly 50-50 chance that global annual temperatures will overshoot 1.5°C this year, with an even stronger possibility of that happening in 2024. A World Meteorological Organization report that came out earlier this year confirmed this analysis and concluded that there is a two-in-three chance that one year in the next five will breach 1.5°C.

A single year at 1.5°C does not yet mean a long-term average, and IPCC targets like 1.5°C are defined as average climate thresholds that last over many years, not a single year. But crossing 1.5°C for a single year would represent the first signal that we are on a path to locking in that temperature for the long term. Climate scientists expect to see a single year of global average temperatures exceed 1.5°C up to a decade before the long-term average passes that threshold. We already got a sneak peek this summer.

Data by Berkeley Earth

“The growing consensus in the field is that we are headed to an overshoot world,” says Zeke Hausfather, climate scientist and energy systems analyst at Berkeley Earth who is also the climate lead for the payment processing company Stripe. “Whether or not we can get to net zero and remove enough carbon from the atmosphere to bring temperatures back down by the end of the century is very much an open question and would involve a huge amount of political will. If any year in the next five years is going to be above 1.5°C, it’s probably going to be 2024.”

So far there is little sign that the world’s top emitters have the political will to slash greenhouse gas emissions. If anything, carbon pollution continues to increase. According to the 33rd annual State of the Climate, an international annual review released jointly by NOAA’s National Centers for Environmental Information and the Bulletin of the American Meteorological Society, greenhouse gas concentrations, global sea level, and ocean heat all reached record highs in 2022.

Most scientists agree that 2°C of warming would risk catastrophic impacts. Yet that threshold could be breached should industrial societies fail to zero out greenhouse gas emissions. Some studies suggest that in a business-as-usual scenario, we could cross that 2°C threshold for the first time within the next 20 years. According to Earth’s Future, a recent NASA study, global temperatures could breach 2°C by 2041 if nothing is done to act on emissions.

Taejin Park, a research scientist at the Bay Area Environmental Research Institute and the lead author of the NASA study, emphasized that such models show that it is still within our power to change that outcome. “Many studies including ours clearly indicate that our actions have a significant impact on the projected changes in Earth's climate and the subsequent effects on us,” Park says. “So, let’s keep in mind that our decisions and actions really matter for our future climate.”

Hausfather emphasized the same point. “Every tenth of a degree matters,” he says. “If we can limit warming to 1.6°C, that’s a lot better than 1.7°C, which is a lot better than 1.8°C. There’s a pretty big solutions space between 1.5°C and 2°C.”

The Magazine of The Sierra Club

The Magazine of The Sierra Club