Facing Intransigence From Manchin, Environmentalists Look for Ways to Slash Carbon Pollution

Advocates and Democratic lawmakers start crafting a plan B

Photo by VanderWolf-Images/iStock

Last week, Senator Joe Manchin, the Democrat from West Virginia who has made a personal fortune from his fossil fuel investments, pulled the rug out from underneath Democrats’ climate agenda. The senator said he would not vote for the Clean Energy Performance Program, or CEPP, the flagship climate policy of the Build Back Better legislation that would require power companies to rapidly replace fossil fuels with renewables such as solar and wind.

The move is a blow to President Joe Biden’s goal to reduce US greenhouse gas emissions by at least 50 percent below 2005 levels by 2030. A recent analysis by the clean energy research firm Energy Innovation found that the loss of the CEPP would cost the reconciliation bill up to one-third of its emissions reductions.

Now, Democrats in Congress and environmental groups are scrambling for a way to fill the gap before Biden leaves for an international climate summit in Glasgow, Scotland, at the beginning of November.

“In the end, the final deal must honor President Biden’s emissions reduction pledge,” said Ben Beachy, the director of the Sierra Club’s Living Economy Program. “If the CEPP is removed, congressional Democrats need to deliver bold new investments to close the gap.”

The CEPP employs a carrot-and-stick strategy to incentivize utilities to ramp up the amount of electricity they produce from renewable sources. Under the CEPP, if a utility increases its share of renewables at the rate set in legislation, it would get a payment (the carrot). If it increases its share at a lower rate, or not at all, it would pay a penalty (the stick).

Without the CEPP, Democrats will have to decouple that pain-versus-gain strategy. Their other meaningful emissions-reduction policy, a 10-year package of clean-energy tax credits (which, for the moment, remains in the draft legislation), could provide the carrot. But what about the stick?

One option Democrats have been throwing around is a carbon fee, which would force polluters to pay for every ton of CO2 they emit. This would likely provide a similar reduction in greenhouse gas emissions to the CEPP.

An analysis by Resources for the Future, a nonpartisan energy research organization, found that the CEPP and clean-energy tax credits would increase the share of renewables in the electricity sector to 78 percent by 2030. Replacing the CEPP with a carbon fee that starts at $15 per ton and escalates to $50 per ton by 2030 would increase the share of renewables in the US electricity sector to 79 percent. That’s just one point shy of Biden’s goal of an 80 percent clean electricity sector by 2030.

“It would be possible to meet the Biden administration’s goals purely through a carbon fee,” said Richard Newell, president of Resources for the Future. “But if you couple it with another policy, like the clean-electricity tax credits, then you could achieve those goals with a carbon fee that is more modest.”

Despite the endorsement of thousands of economists who say a carbon fee is the most effective way to reduce the greenhouse gas emissions that are warming the planet, politicians have tended to view it as a nonstarter. This summer, an undercover reporter for Greenpeace recorded a lobbyist for ExxonMobil saying that the oil company supported a carbon fee—only because it knew the policy would never pass. Environmental justice groups have warned that a carbon fee could end up being a regressive tax and have generally been critical of the idea. In July, The Atlantic eulogized the carbon tax in a mock obituary.

Still, for a few days last week, there was hope that Manchin might get behind the idea of a carbon fee. His alleged concern with the CEPP is that it uses “taxpayer dollars to pay private companies to do things they’re already doing.” And it’s true, renewables are increasing. Last year, they surpassed coal and nuclear to become the country’s second-largest source of electricity. But the shift is not happening nearly fast enough. Less than a dozen of the nation’s thousands of utilities are increasing their share of energy by 4 percent each year—the rate that’s needed if the United States is to meet Biden’s target.

If handouts are all Manchin is worried about, it seems a carbon fee would check all his boxes. Because it’s essentially a tax, it could be passed through Congress’s complicated budget reconciliation process. It would also be cheap: Democrats had proposed spending more than $150 billion on the CEPP, but a carbon fee would cost nothing—it would actually raise money. Problem solved, right?

Wrong. Manchin slammed the door on a carbon fee as well, telling reporters last week that the policy was “not on the board at all right now.” In hindsight, Democrats should have known there wasn’t much hope. After all, Manchin did fire a rifle at the Obama administration’s version of climate policy in a campaign advertisement during his first run for the Senate. Recently, it’s become clear that Manchin’s true beef with Democrat’s climate goals isn’t “how” to eliminate fossil fuels but the very idea of eliminating them at all.

So, if not a CEPP or a carbon fee, what else?

Another analysis published last week by the research firm Rhodium Group found that it is possible to meet Biden’s emissions reduction target without a carbon fee or CEPP. That, however, would require Congress to pass the dozens of additional climate investments still in the reconciliation bill either unadulterated or even expanded (a prospect that is very much uncertain with Manchin still wielding the scalpel). At the same time, there would need to be a concerted regulatory effort from the White House, states, cities, and corporations to bring down carbon pollution.

“There’s no single new policy that will fill the emissions gap left behind by the CEPP,” Beachy said. “Instead, we’re going to need a bundle of new, bold climate investments. The climate crisis is an economy-wide problem, so we’re clearly going to need economy-wide solutions.”

Up until now, Democrats’ strategy to meet Biden’s emissions reductions target has been to rapidly decarbonize the electricity sector. Indeed, most analyses show that decreasing emissions from electricity generation is by far the best way to reduce the most emissions in the shortest time. Even in the Rhodium Group’s sprawling scenario, most of the emissions reductions would come from the electricity sector.

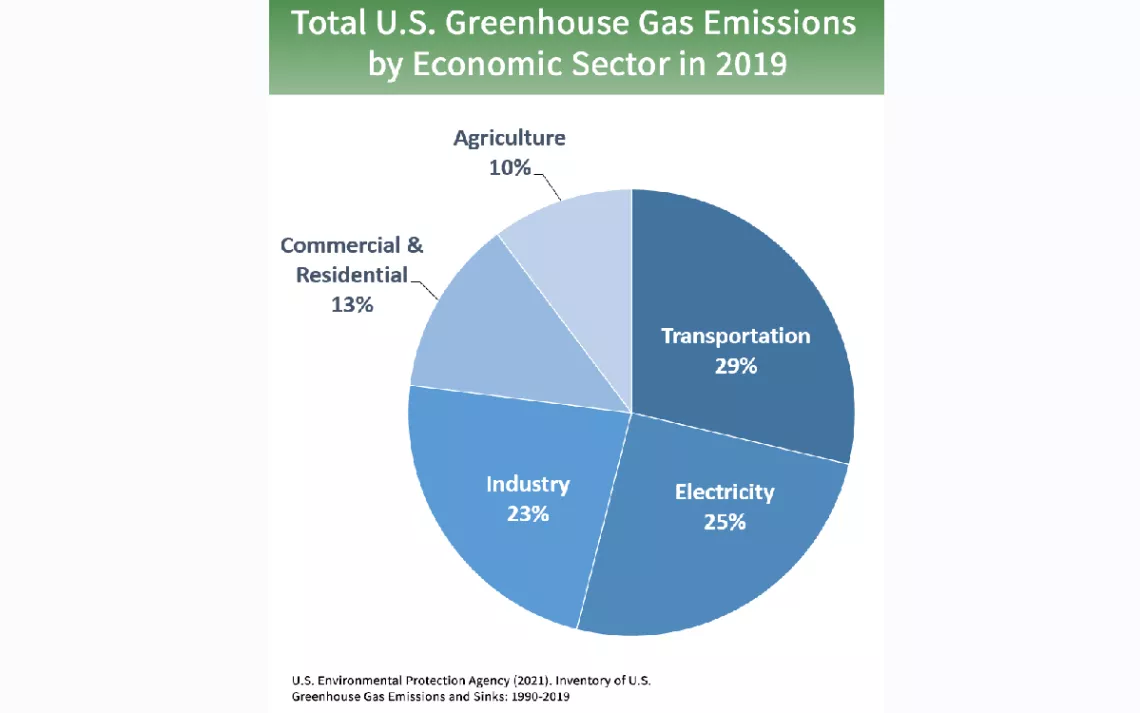

But power generation is not the largest source of greenhouse gas emissions in the United States. That’s transportation, which accounts for 29 percent of total US greenhouse gas emissions, according to the EPA. Slashing carbon pollution from America’s personal cars and trucks, freight, and buses is therefore imperative to bringing down overall emissions. The Sierra Club and other environmental organizations are pushing legislators to include a number of transportation-related measures to ratchet down tailpipe emissions. They include electrifying and expanding public transportation, electrifying the nation’s fleet of 60,000 school buses, and expanding the tax credits for people buying electric vehicles.

Cutting US emissions at a scale scientists say is needed will also require tackling emissions from the American manufacturing sector, which accounts for 23 percent of total US greenhouse gas emissions—and an even larger share when you include both the emissions factories produce directly and the emissions produced from generating the electricity they use. What’s more, US industry’s greenhouse gas pollution is expected to increase by about 18 percent through 2050—undercutting many of the emissions reductions the Biden administration might achieve from power and transportation.

At the same time, the United States has a shortage of manufacturing facilities for producing electric vehicles, wind turbines, and solar panels, all of which it is going to need in the transition to a clean energy economy. “We rely on importing clean energy goods from countries with low labor and environmental standards,” Beachy said. “Electric vehicles made with steel that is twice as polluting as US steel. Solar panels built with forced labor. US workers lose out while clean energy businesses risk supply chain shortages that could hamper the transition.

Yet the reconciliation bill is surprisingly mum when it comes to industry, Beachy said. This is a wasted opportunity. According to the Center for American Progress, every $10 billion invested in decarbonizing industry would cut more than 30 million metric tons of CO2. This appears to be one area where Democrats could try to close the gap left behind by the CEPP while setting the United States up for a successful transition to a clean energy economy in the years to come. After all, a 50 percent reduction by 2030—while a laudable goal—is still only halfway there.

“This is a real opportunity staring us right in the face right now,” Beachy said. “Congress could usher in a new era of clean manufacturing that bolsters the health of frontline communities, creates jobs, lowers emissions, and delivers the clean energy future.”

The Magazine of The Sierra Club

The Magazine of The Sierra Club