EPA Puts the Pedal to the Metal to Electrify Transportation

New guidelines will dramatically accelerate EV adoption

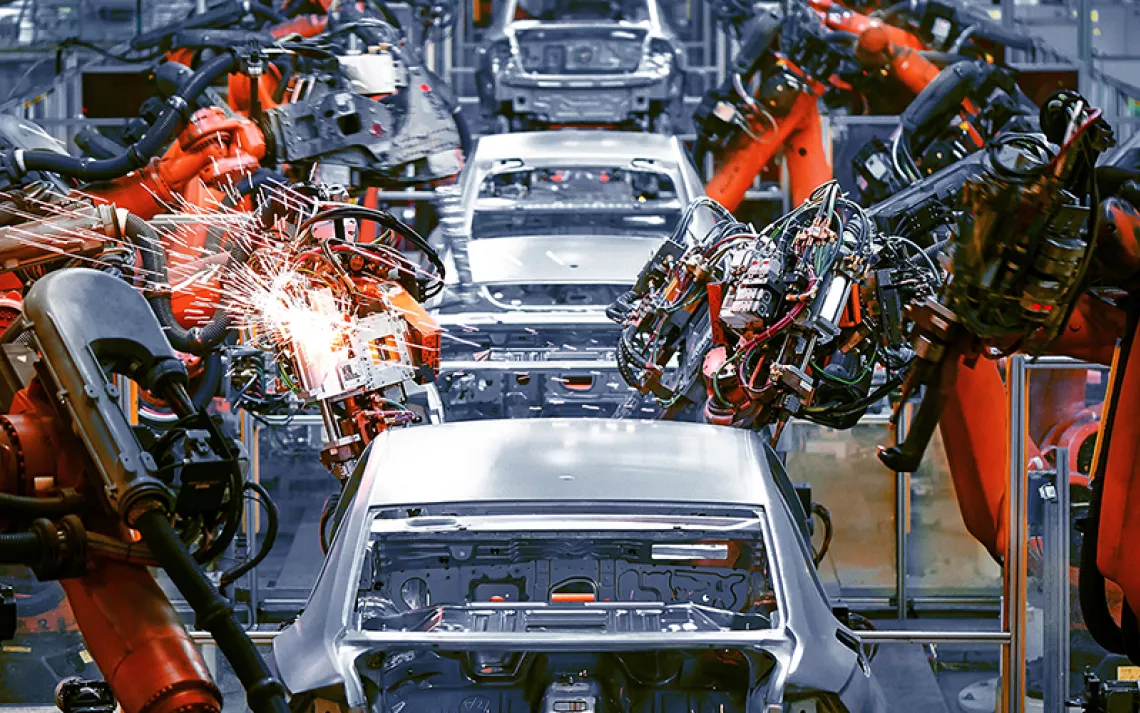

Photo by peeterv/istock

|

In a historic move, the Environmental Protection Agency this week announced new proposed tailpipe emission standards for light vehicles that could increase the new electric vehicle market share by tenfold in a single decade—from 5.8 percent in 2022 to as much as 67 percent by 2032.

EPA administrator Michael Regan called the new proposals “the strongest-ever federal pollution standards for cars and trucks together" and said, "These actions will accelerate the ongoing transition to a clean vehicles future.”

“The proposals are critically important for combating the climate crisis,” says professor Gregory Dotson, head of the Energy Law and Policy Project at the University of Oregon. “Transportation is now the single-largest source of greenhouse gas emissions in the United States. And light-duty vehicles are the single-largest portion of transportation in the country. This is the largest move in the history of our federal government to promote zero-emission vehicles.”

The standards, which would apply to new passenger vehicles beginning in 2027, would reduce carbon dioxide emissions by 7.3 billion tons through 2055, according to EPA’s analysis. The agency also announced new emission standards for heavy-duty trucks starting in 2023 that would cut an additional 1.8 billion tons of CO2.

“Reducing emissions is not only important from a climate change perspective,” Dotson adds. “It’ll also improve health in our communities.” That’s because in addition to CO2, internal combustion engines emit a mixture of other harmful pollutants, including nitrous oxides, sulfur oxides, benzene, formaldehyde, and fine particulates. Health impacts from this air pollution include asthma, bronchitis, heart disease, and cancer. Worldwide, tailpipe emissions kill about 20,000 people every year.

“In the US, those health impacts disproportionately affect Black and Hispanic communities,” explains Dr. Shelley Francis, a public health expert who is the first Black woman to serve on the board of the Electric Vehicle Association. “That’s a direct result of things like red-lining and transportation policies that placed highway corridors through communities of color. So these stricter emission standards will have a huge impact on the public health and well-being of folks residing in those communities.”

The United States lags behind several other nations in transitioning to electric vehicles, including the 27-member European Union, which recently banned the sale of new gasoline- and diesel-powered vehicles after 2035 while also mandating a 55 percent reduction in CO2 emissions for new cars in 2030.

“This is still a really big deal for the United States,” says professor Jeremy Michalek, who directs the Vehicle Electrification Group at Carnegie Mellon University. “These standards are the single most consequential policy affecting the largest source of GHG in the US. That sends a very strong signal to automakers to accelerate the shift toward electric vehicles.”

The new standards also represent one piece of a much larger puzzle. National electrification, transitioning all sectors of society off of fossil fuels, will require a Herculean effort. Another piece of the transportation puzzle is a massive increase in the number of public charging stations to accommodate all the new EVs.

“Right now, we’re not super dependent on public charging,” Michalek says. “But that’s going to change with the kind of numbers the EPA is pushing.”

Most EV owners today have chargers installed at home, usually in their garage. But as households without off-street parking swap out their gas-powered vehicles for EVs, more charging stations will need to be installed in public areas.

“People who live in apartments or in older housing without a garage will need a dependable way to charge their EVs,” Michalek says. “And that means more public charging stations.”

According to University of Oregon’s Gregory Dotson, the Biden administration and Congress anticipated the need for an expanded EV charging infrastructure. Dotson served as the Democratic chief council for the Senate Committee on the Environment and Public Works in 2021 and 2022, where he helped write the Inflation Reduction Act and the Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act. Each contains billions of federal dollars for public charging stations.

“We created new programs for states to do EV charging infrastructure and a community-charging program,” he says. “That’s another huge pot of money that allows them to build out EV charging stations wherever they choose, not based on proximity to federal highways.”

Which leads to another piece in the electrification puzzle: All those vehicles charging their batteries will put new demands on the nation’s aging electrical grid. “There’s still lots of spare capacity in the system,” Dotson says, “but we need to do a lot of work on the grid over the next 10 years. And over the next 20 years.”

While the enormity of the job may seem daunting, Dotson insists it’s both possible and necessary: “I haven't seen anything that says that the grid is a reason not to move to zero-emission vehicles. What I have seen is arguments that as we move toward zero-emission vehicles, and we generally try to electrify energy uses in a way that's going to be more sustainable, there's going to be a lot more electricity infrastructure needed.”

For those who doubt America’s capacity to make such large changes in the Biden administration’s timeframe, many experts point to the example of Norway. Last year, nearly 80 percent of all new cars sold in that country were fully battery powered, thanks in large part to a package of government financial incentives and simultaneous build-out of fast chargers in both urban and rural areas. At its current pace, Norway should reach its target, set in 2016, of 100 percent zero-emission new cars by 2025.

“Every country is different,” Michalek cautions. “I don’t think we can directly copy any other country’s models. But Norway does provide lessons we can learn from.”

One prime lesson is that transportation electrification depends on having a government that sets specific ambitious goals, a timeline for achieving them, and then creates a package of regulations and incentives for getting there. And, adds Dotson, never giving up when inevitable setbacks occur.

“During the 2000 presidential campaign,” he recalls, “Vice President Al Gore talked about phasing out the internal combustion engine. Twenty-three years later, the internal combustion engine is on the decline. Would it have been very valuable to have achieved emissions reductions much sooner? Sure, but we are where we are. And we now seem well on our way to transitioning to zero-emission vehicles.”

The Magazine of The Sierra Club

The Magazine of The Sierra Club