Ecologist Jennifer Grenz Has a Plan to Decolonize Land Management

Her university lab applies Indigenous values to restoration ecology by collaborating with communities

Jennifer Grenz runs the Indigenous Ecology Lab at the University of British Columbia, where she's applying Indigenous worldviews to her restoration projects and incorporating local knowledge. | Photo by Paulo Ramos/UBC Forestry

The Garry oak ecosystem in western Canada is one of the country’s most endangered. Just 3 percent of the original ecosystem remains, yet it contains about one-fifth of the country’s at-risk plant species. It’s also a historically important food system for the Coast Salish people, who rely on these forests for starch farming. But years of fire suppression have allowed the forest canopies to sprawl so much that low-lying plants no longer have the space and sun to grow. When the tribes suggested felling some of the trees, people in nearby nontribal neighborhoods protested.

“This is the problem of environmental education now,” said Jennifer Grenz, a Nlaka’pamux restoration ecologist at the University of British Columbia and the author of Medicine Wheel for the Planet, whose family comes from the Lytton and Bonaparte First Nations. Even though tribes maintained this landscape with fire for centuries, an othering of “nature” has trained people to think of human-managed landscapes as unnatural, she explained. “Indigenous practices shaped landscapes since time immemorial,” Grenz said. “All of these landscapes require human relationship.”

At the University of British Columbia, where she runs a lab focused on decolonizing ecology, Grenz leads with a strong message to her students: “We are disruptors.” By prioritizing Indigenous communities and their needs in her research, her goal is to inform more equitable land stewardship in a way that treats invasive species management, food systems, and restoration as one.

The backdrop to Grenz’s ecological work is rooted in her family’s story. Canada’s genocide of Indigenous peoples meant the only way for her ancestors to survive was to hide in plain sight. Their greatest accomplishment, her elders told her, was avoiding registration under the Indian Act by pretending to have a different identity. “Now that I'm older, I realize how Indigenous my upbringing was without really recognizing it as such, because assimilation was how people survived a lot of racism,” she said. “Our family’s reclamation of identity is so deeply tied to this cultural resurgence and reclamation of our land stewardship.”

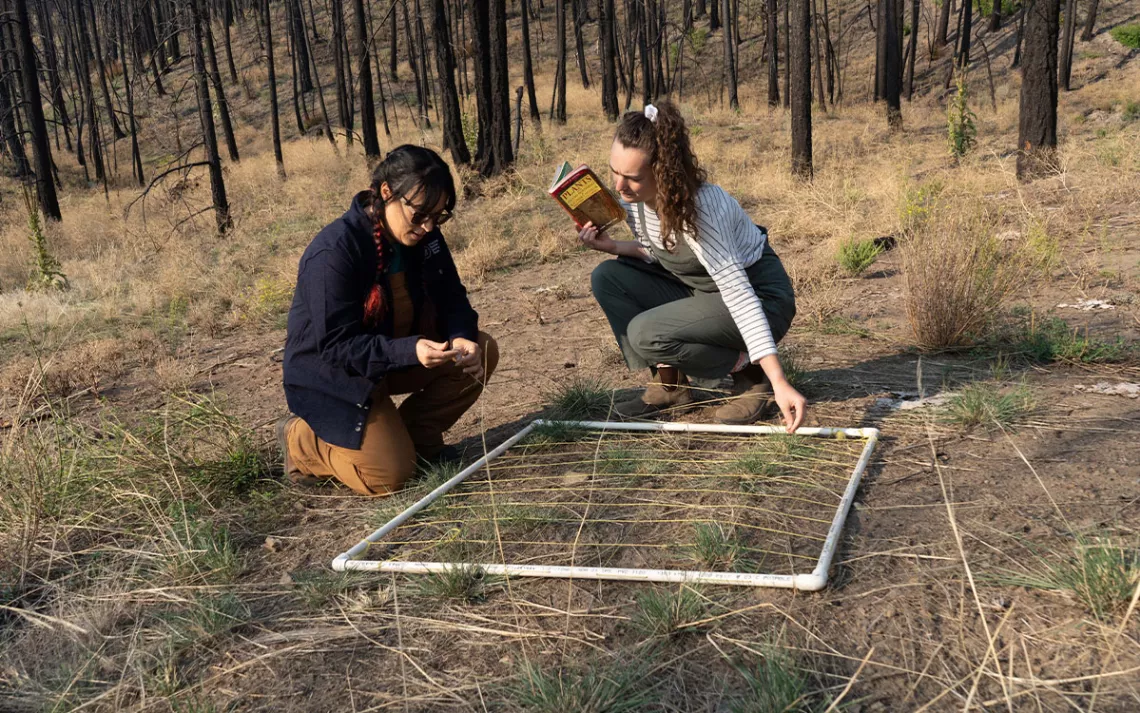

Jennifer Grenz and UBC graduate student Virginia Oeggerli assess invasive and culturally important plant species affected by the McKay Creek Wildfire in St'at'imc Nation territory, north of Lillooet, British Columbia.| Photo by Cheyanne Watkinson

Grenz is no stranger to assimilation in her own career. “I was speaking at a weed science conference and got told I didn’t have enough letters after my name,” Grenz said. So, mid-career, she went back to school for her PhD in integrated studies in land and food systems. After she graduated, restoration ecology still seemed broken as a discipline: Projects were failing, good intentions fell short, and the endless publishing sprint of academia felt disingenuous. It sparked the idea for her Indigenous Ecology Lab.

The land stewardship Grenz seeks often seems at odds with Western ecology, a friction she’s trying to smooth. Her lab prioritizes Indigenous values—such as reciprocity and respect for nonhuman and even nonliving beings—in restoration and management decisions. But Western approaches have overlooked the ways Indigenous communities actively shaped those landscapes, she explained.

When settlers arrived on Vancouver Island in the mid-1800s, they saw boundless resources, “But what they didn't see was the purposeful shaping of food and technological systems for thousands of years to provide that so-called bounty,” she said. Trees, for example, were spaced out in a specific way to achieve different growths for creating different types of canoes. From an Indigenous worldview, people are part of the natural environment, not separate from it.

As an educator, Grenz appreciates the opportunity to teach and work alongside the next generation of land stewards both with and without Indigenous ancestries.

Chelsey Geralda Armstrong, a historical ecologist and ethnoecologist at Simon Fraser University, met Grenz at a Ts'msyen site in Kitselas First Nation near Terrace, British Columbia. She was researching ancient forest gardens, which are forested areas where people have cultivated berries and nuts for millennia. Other colleagues felt like productive partnerships, Armstrong said, “but I think her and I just fell in love.”

Their friendship grew out of a joint mission to bridge the gap between Western and Indigenous values, which they’ve explored for invasive plants. Western management typically says to eradicate what doesn’t belong, but this recipe doesn’t always work, Grenz said. At one ancestral site belonging to the Cowichan—the largest First Nation band on what is now known as Vancouver Island—a nonnative plant called Canada thistle has grown rampant. The usual course of action would be to remove all the plants, but Cowichan elders hit pause: What would happen to the eight native pollinator species they observed resting atop the beds of thistle if they were removed? Instead of ripping out the plants immediately, Grenz’s team planted other species that would attract pollinators with good food and habitat before removing the invasive ones.

Yet there’s a long way to go in achieving this renewed perspective in land management on a wider scale, Grenz and Armstrong agreed. This doesn’t mean there’s no place for ecology, Armstrong noted. Rather, scientists need to be open to thinking about their work in a new way. In the same spirit, Armstrong, who refers to herself as a settler scholar, said she values learning when to step back and create space for underrepresented communities. Efforts to incorporate traditional ecological knowledge, often abbreviated as TEK, are remiss if they don’t account for each individual community’s needs and values. And in some places, the term TEK has become more like a flavor of the month, Armstrong added, with some scholars extracting only pieces of knowledge in a copy-paste way, overlooking a community’s individualism.

Government-led restoration efforts feel “more like covering up the scar on the landscape,” Grenz said, rather than healing it. Decades of land preservation that preclude human management—such as fire suppression leading to raging, uncontrolled fires—have contributed to many of the region’s current environmental battles. “Until regulators can change their entire worldview to look at an ecosystem and say, ‘That's your kin,’ then they're never going to be able to manage it in a way that will sustain us through this kind of climate crisis,” Armstrong said.

Rewriting the rules of research hasn’t been straightforward at a higher education institution rooted in colonial history. But it’s an ongoing learning experience—for Grenz, through identity, and for settler colleagues like Armstrong, through openness to change.

“If there's anything an Indigenous worldview taught me, it's that it’s not about putting things back,” Grenz said. “It's about looking ahead. It’s about honoring the stories of the past, of the land, and the present, but creating a new story for the future.”

The Magazine of The Sierra Club

The Magazine of The Sierra Club