The Dam That Wasn’t

Fifty years ago, activists fought off a dam in Illinois. Their story has a lot to teach us.

Bruce Hannon and other members of the Coalition to Save Allerton Park deliver a petition to Congress with 20,000 signatures. | Photo courtesy of Prairie Rivers Network

On an unusually warm January day, I drove 30 miles west from my home in Urbana, Illinois, to Allerton Park—a 1,517-acre woodland park and retreat center on the Sangamon River. I parked my car, leashed my dog, and headed down the trail. President Trump had just issued his executive order banning immigrants from seven majority Muslim countries, and my nerves were on edge. But as I strolled into the woods, the layers of tension slipped away, and my mind quieted. I crossed a meandering stream, watched a pileated woodpecker flit by, and stood on a ridge above the emerald-green river. The water trembled in the wind.

When you live in the flat, monocultured industrial landscape of east central Illinois, a patch of native river bottomland like the one preserved at Allerton Park is a rare gem. Not only does it sustain the physical and psychological health of the people who walk here, it supports the mission of the University of Illinois, which owns and manages the park. Ecologists conduct research here; departments make use of the Allerton mansion and grounds for retreats; art history students observe its collection of statuary; artists and musicians stage performances. It’s an invaluable public resource—one that would not be here today if it weren’t for a group of dedicated citizens who fought to save it 50 years ago, just as the nation’s environmental consciousness was stirring. Their fight serves as an inspiring model for activists facing the Trump administration’s relentless attacks on the environment.

The battle for Allerton Park began with a hike by another woman through the very same woods. In the summer of 1967, Patricia Hannon and her family were vacationing at a camp adjacent to Allerton. One morning, she opted to take a guided tour of the woods while her husband, Bruce, stayed in the cabin, refinishing an old violin. On the hike, Patricia learned some devastating news: the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers planned to build a dam downriver; the resulting reservoir would flood Allerton Park.

Patricia flew back to the cabin to break the news to Bruce, who was so shocked that he sat down on the violin, crushing it beyond repair. It was just as well; another more pressing project was at hand.

That evening, around a camp bonfire, Patricia explained the situation to the gathered group of fellow campers. Five years earlier, in 1962, Congress had authorized the Army Corps’ proposed expenditure of $27 million to build the Oakley Dam, which would create a reservoir eight miles long and 621 feet above sea level. The Corps argued that the project would control flooding, supplement the city of Decatur’s water supply, which had been compromised by agrichemical pollution and excessive siltation, and offer new recreational opportunities.

Then, Patricia went on, the previous year the Corps doubled the scope of its original plan: Oakley Dam would now rise to 60 feet, creating a reservoir 24 miles long and 636 feet above sea level at a new price tag of $64 million. This expanded reservoir would have the added benefit of diluting sewage from the city of Decatur (a process known as low-flow augmentation). It would also flood close to 1,000 acres of Allerton Park.

Patricia circulated a petition, which quickly filled with signatures. On their way back home to Champaign-Urbana later that week, she turned to Bruce and said, “It’s yours, now.”

From left: Bruce Hannon, Jack Paxton, and John Marlin | Photo by Robert Hirschfeld

The Hannons were a traditional family unit. They had four small children, who were largely Patricia’s responsibility; Bruce won the family’s bread as an assistant professor of engineering at the University of Illinois. He was also a half-time graduate student, working on his PhD in theoretical and applied mechanics. But he didn’t shirk from the challenge. He wrote a letter to the editor of the local newspaper, which attracted other outraged citizens, who joined forces with Bruce. They called themselves the Committee on Allerton Park (COAP), and they began to organize.

Their immediate task was a massive education effort to recruit people to their cause. Bruce traveled the state, speaking to garden clubs, environmental organizations, and other interested groups—anyone who would have him. He devised a diagram—three rings, linked to form a triangle—to help him describe the way the Corps worked with elected officials and vested interests to push through its projects, regardless of their potential ecological damage. (Bruce’s model eventually became known as the Iron Triangle, and earned him a job offer from the University of Illinois’s political science department, even though his expertise was in engineering. He declined.) In the case of Oakley Dam, the three corners of the triangle—the players who stood to gain—were the Corps’ Chicago office, which would add another federally funded project to its list of achievements while keeping its workforce busy; the Decatur Chamber of Commerce, which welcomed the projected increase in tourism and development dollars; and Representative William Springer, who was the representative for Illinois’s 22nd district. “A dam is concrete evidence that a congressman has done something for his or her district,” said John Marlin, a key COAP player who joined in 1970, when I spoke to him at his office. In other words, classic pork barrel politics.

The COAP’s plan was to pry the Oakley iron triangle apart.

First, they worked on Representative Springer. At the end of 1967, the COAP delivered to his office Patricia’s petition, heavy with 20,000 signatures. Springer, along with Illinois senators Charles Percy and Everett Dirksen—all of whom had come out in support of the dam—asked the Corps to re-evaluate.

Next, they gathered data. Rich in scientists and engineers who knew how to speak the Corps’ language, the COAP analyzed the project’s purported benefits—flood control, water supply, recreation, and low-flow augmentation—and came up with some contradictory findings, among them that the Corps had exaggerated flood damage on the Sangamon River by about 5 to 1; that Decatur’s water needs could be met by tapping an underground aquifer, which would provide cleaner water at a cheaper price; and finally, that the much-touted recreational benefits didn’t take into account the loss of the woodlands enjoyed by users of Allerton Park or the likely eventuality that swimming would be unpleasant in the new reservoir because of the inevitable build-up of siltation and agrichemical pollution as well as the stinking mudflats that would result from the yearly summer draw-downs necessary for low-flow augmentation. The Corps, they argued, had exaggerated the project’s benefits while understating its costs.

Armed with data, the COAP used it in all of its communications, which was a massive effort, particularly in those pre-internet days. One member, Ann Simonton, along with many of her friends, sent letters to 125 different organizations throughout Illinois asking that they contact their representatives and providing talking points, handwriting the contact information for each representative. Bruce recruited Jack Paxton, who had started the local Sierra Club chapter, to help lead the COAP; those chapter members also wrote letters. (Bruce heard from Senator Charles Percy that he received more mail on Allerton Park and the Oakley Dam than he did on Vietnam.) And they continued to collect signatures, reaching a total of 80,000 on a 1968 petition.

This extreme popular pressure, paired with the data that questioned the accuracy of the Corps’ numbers, began to loosen the links between each corner of the Iron Triangle.

Meanwhile, the Corps responded with 12 alternative proposals, none of which satisfied the COAP, as they would all still flood Allerton. The COAP countered with an alternative suggestion: Reduce the reservoir height to the originally proposed 621 feet, and include a greenbelt recreation area along the lower Sangamon. The Corps refused.

Around that time, John Marlin, then a senior at the University of Illinois, approached Jack Paxton and asked how he could help. Jack sent him to Bruce, who brought John “banker’s boxes full of documents” and asked him to put them into a book that would lay out the entirety of the COAP’s argument. The resulting publication, Battle for the Sangamon, included writings by eminent zoologist S. Charles Kendeigh and world-famous entomologist Robert Metcalf, among others, all presenting expert arguments for the preservation of Allerton Park. The book became a reference for dam fighters all over the country.

“Every dam,” John Marlin told me, “had a core group of opponents—farmers who were going to lose their land, canoeists who used the river, and a few people concerned about a county tax base. It became clear to me that if we were going to defeat the Oakley Dam, we had to broaden the base of opposition.” John began to communicate with these local opposition groups, including groups opposing the Merrimack Dam in Missouri, the LaFarge Dam in Wisconsin, and a group called Rivers Unlimited fighting several dams in Ohio. Together they formed the Coalition on American Rivers.

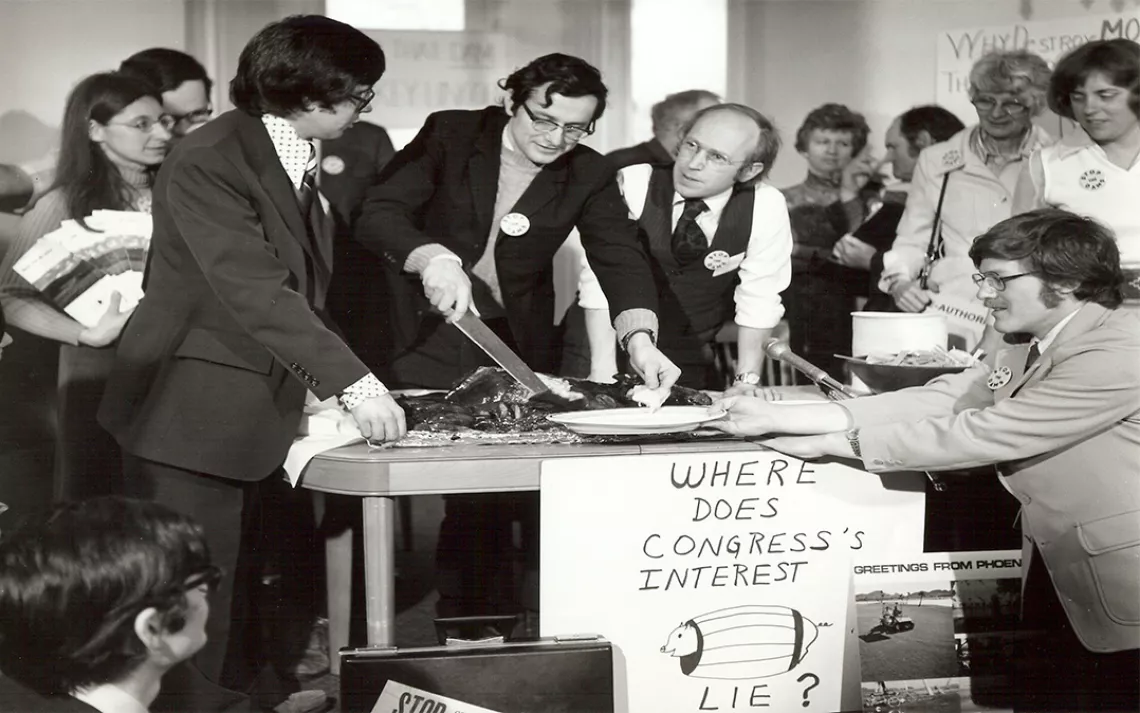

Pork in D.C., 1977: At a press event in Washington, D.C., to protest pork barrel water projects. Brent Blackwelder is cutting the piglet. On the far right is John Marlin. Connie Wick, who organized the opposition to the Wildcat Creek Dam in Indiana is second from the right, above Marlin. | Photo by John Marlin

Every year from 1976 to 1986, during the congressional appropriations hearings, the coalition would come together to testify before Congress, argue their positions to individual representatives, and then convene at the National Dam Fighters Conference—organized by Brent Blackwelder, founding chair of American Rivers and former president of Friends of the Earth—to exchange ideas and develop strategies. “It was very much like we were waging a guerilla war against an established government,” said John Marlin.

Meanwhile, the public’s environmental consciousness was beginning to rise. The country was waking up to the reality of pollution and the concomitant threats to the land and waterways so many people enjoyed. In 1969, Congress passed the National Environmental Policy Act, which required all federal agencies to evaluate the environmental impact of any proposed project. (One of the first environmental impact statements filed by the Corps was on the Oakley Dam, according to Jack Paxton. “We rather shredded it,” he said in a recent interview.) In April 1970, the first Earth Day was observed. Articles questioning the Corps appeared in popular national magazines like The Atlantic Monthly, Time, and The Christian Science Monitor. Supreme Court Justice William O. Douglas, an avid conservationist, denounced the Corps as “Public Enemy Number One” and, at the request of the COAP, led a hike at Allerton Park in May 1969. A few months later, he cited Oakley Dam as a prime example of a poorly conceived Corps project in an article for Playboy called “The Public Be Dammed.”

After years of relentless campaigning against all three corners of the triangle, the COAP began to see some encouraging results. An internal 1973 Illinois EPA report predicted the Oakley reservoir would be “shallow, silty, turbid, algae-ridden, and frequently in violation of public health standards,” a description the COAP gleefully leaked to the Chicago Sun Times. A few high-profile Corps-constructed failures, including the Carlyle Reservoir in southern Illinois, which caused significant crop damage to downstream farms, bolstered the COAP’s argument and helped the COAP recruit more farmers to their cause.

Meanwhile, the Corps augmented its numbers yet again, estimating a staggering new cost of $110 million, up from the originally proposed $21 million. In their new calculations, recreation had become the largest projected benefit at 53 percent of the total (up from 9 percent), even though the Corps had already declared that the Oakley Reservoir would not be suitable for swimming. “It’s obvious,” wrote John Marlin in a 1974 COAP press release, “that the Corps of Engineers is simply making up the benefit-cost analysis.”

The following year, the COAP convinced Senator Percy’s office to request an external review of the project. The GAO’s report was damning. It asserted that many of the benefits that the Corps claimed the project would produce—recreation, most notably—were “questionable,” and with these questionable benefits removed from the calculations, the benefit/cost ratio plummeted. It was a no-brainer; the Oakley Dam would be scrapped. The COAP had won.

Fifty years later, John Marlin’s Coalition on American Rivers has evolved into the Prairie Rivers Network, a regional organization advocating for healthy waterways, based in Champaign, Illinois. One of its recent achievements was to stop the construction of a new levee on the Mississippi River near New Madrid, Missouri, that would have destroyed an essential wetland. This year, it celebrates its 50th anniversary; one event will take place at Allerton Park.

Today, as the Trump administration works to reverse President Obama’s clean-energy legacy and threatens to do away with the Environmental Protection Agency altogether, the story of how Patricia and Bruce Hannon, Jack Paxton, John Marlin, and all the hundreds of volunteers for the COAP stopped the Oakley Dam offers hope and inspiration. It took diligent research, sustained and creative campaigning, and a strong coalition of sometimes unlikely alliances. But their persistent efforts to pry apart that iron triangle paid off. It’s a strategy we need now more than ever.

Turns out iron, under the right kind of pressure, is more malleable than it seems.

The Magazine of The Sierra Club

The Magazine of The Sierra Club