Wildland Firefighters on the Front Lines

Inside the lives of these people who risk their lives

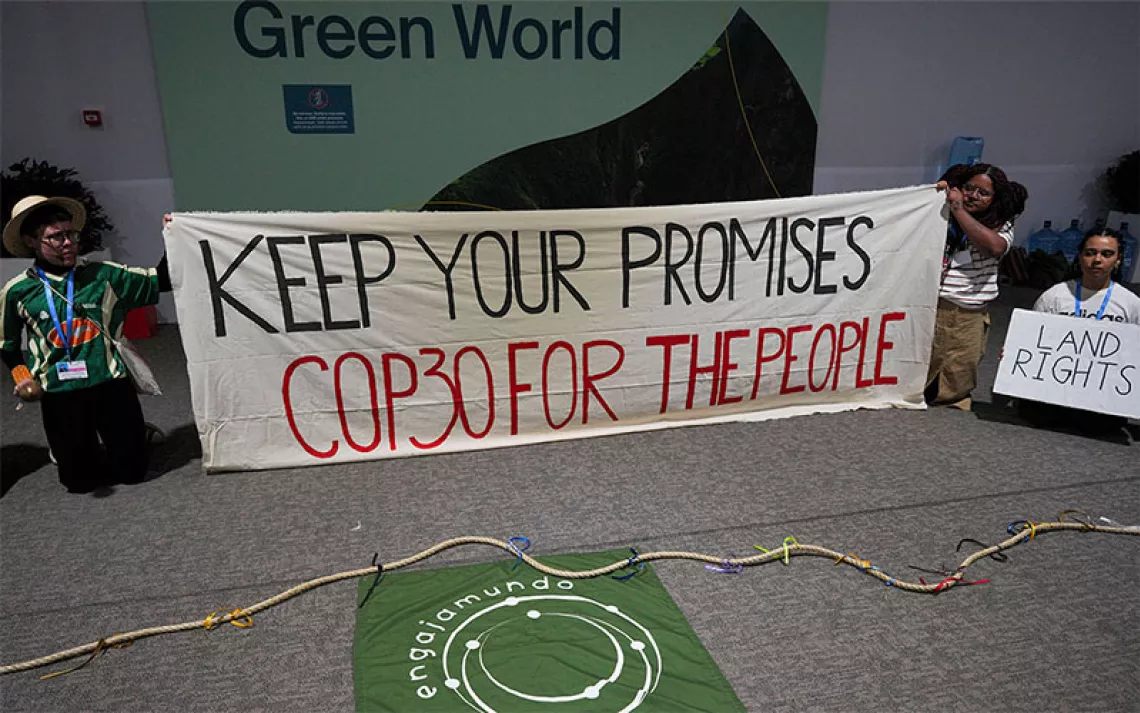

The Coffee Creek Correctional Facility fire crew cuts a line in Oregon.

MORE THAN HALF of the firefighters in the United States are volunteers, often holding down other jobs when they're not combating fires. Some do it out of a commitment to community, others because they want to gain some experience in the field before looking for a paid fire gig. As climate change continues to alter the planet, some will find themselves working on the front lines of the most intense wildfires in a generation. What unites all wildland firefighters, whether they're paid or volunteer, are the risks they take every time they suit up.

Riva Duncan

Riva Duncan spent 31 years fighting wildfires for the US Forest Service as a hotshot and eventually as a forest fire chief until she hit mandatory retirement. She felt lost without the work—until she found a new way to fight fire. Duncan is now the executive secretary of Grassroots Wildland Firefighters, a volunteer-run nonprofit that advocates for policy reforms to improve the pay, health benefits, and well-being of wildland firefighters. "I got tired of the inaction," she says.

Wildland firefighters are regularly exposed to smoke and toxins, but they aren't afforded the same health-care coverage for work-related illnesses as structural firefighters. Trauma-informed mental health care is limited. In current government parlance, they're "forestry technicians," not first responders or firefighters; reclassification would go a long way toward recognizing the danger and the sacrifices they are making, Duncan says. In June, a temporary bump in pay was announced for federal wildland firefighters (it's expected to expire in 2023). And in July, the House of Representatives passed the Wildfire Response and Drought Resiliency Act, which, among other provisions, increases the base pay for wildland firefighters to $15 an hour and provides for a seven-day mental-health leave. "It is just the first step," she cautions. "It is what we call the Band-Aid."

These firefighters are employed by private outfits as well as a mishmash of federal land-management agencies and state and municipal departments. Some of them are incarcerated and earn as little as $2 to $5 a day. Approximately 20 states—including nearly every state in the West—use inmate fire crews as a source of cheap labor for increasingly dangerous work.

Spurred by climate change and decades of inadequate forest management, wildfires are growing hotter and larger. At the same time, there are fewer people available to fight them. In May, the Forest Service, which employs the majority of the country's 20,000 or so wildland firefighters, was short by about 25 percent of its needed staff. Promised pay raises have been slow to come through, and there's only so long someone can slog through 16-hour shifts day after day for months on end. Fire seasons today are 78 days longer, on average, than they were in 1970.

Who are these individuals who put so much at risk to defend against wildfires? And what is the job costing them?

Julius Hostetler

Julius Hostetler was born into wildland firefighting: His father and mother both had lengthy firefighting careers. Hostetler is now the superintendent of the tribally managed Geronimo Interagency Hotshot Crew, one of seven hotshot teams overseen by the Bureau of Indian Affairs. The Geronimos are based on the San Carlos Apache Reservation in Arizona, and most of the crew, including Hostetler, are members of the Apache Tribe. "Where we come from, it's not a place of opportunity. There's poverty. A lot of these guys come from broken homes. . . . The education is not highly ranked in the state of Arizona," he says. "So, this is probably one of the best outlets I see, as far as opportunity for our people."

Hostetler's entire 24-year career has been with the same 20-person crew, and 2022 has been one of its busiest seasons yet. Hostetler left his fiancée and their children for more than 100 days between April and August. The guilt of being away from them, he says, "is the heaviest thing I carry."

Amanda Burciaga

The sky was an inky black as Amanda Burciaga dug lines on her first fire. She was exhausted from working overnight. And elated. This, she felt, was something she could do every day for the rest of her life.

Burciaga lived next to a fire station as a kid. In 2010, she was sentenced to 10 years in prison. During the second half of her stint, after being moved to the minimum-security Coffee Creek Correctional Facility south of Portland, Oregon, she saw women running across the yard to put on boots. She was intrigued. Coffee Creek founded the state's first women-inmate fire crew in 2015. These firefighters work alongside federal, state, and local firefighters. They fight the fire like everyone else. And like professional firefighters, they have to pass a physical fitness assessment and basic wildland fire courses and get certified in first aid and CPR. The freedom to walk through the prison gates, and the chance to be in nature and do work of value, drew Burciaga to the job. "The best thing about getting to go out was feeling like a person again," she says. Since she was released in 2020, Burciaga has been working on a seasonal engine crew with the Oregon Department of Forestry.

Luke Mayfield

In March 2019, after 18 years with the Forest Service (including a dozen as a hotshot), Luke Mayfield was done. The impacts on his health had proved to be too much. He was 39 years old. Before and after each fire season, he'd fall into a funk and self-medicate with beer and whiskey for months; he had an anxiety attack while sitting alone in his truck. He watched as his colleagues dealt with divorce, depression, and substance abuse.

In the off-season, mental-health struggles can become more pronounced as firefighters lose touch with their crewmates and shift from the energy of working on the line to home life. Today, Mayfield is working in wildfire-adjacent jobs, as the fire program manager for a company that makes wildland fire gear in Bozeman, Montana, and as the cofounder of Grassroots Wildland Firefighters, which lists mental health as one of its core missions. "I just want the folks that I consider my fire family to be taken care of and be able to successfully go through their career and step out the other side of it whole," he says.

Jesse Corwin

Jesse Corwin was introduced to firefighting when he served on an inmate crew in his early twenties in Oregon. He worked his way up to the lead foreman position and continued in the industry once he was released from prison, eventually transitioning to a private firefighting contract crew. Corwin has fought at least 50 fires across the West. "It's kept me on a really good path," he says of his career choice. "At the end of the year, I feel like I'm always this way better person."

Private firefighting affords him more stability than, say, being part of a hotshot crew, for which he'd likely have to relocate for the summer. It also earns him more money, since some private jobs pay better than federal work. Corwin's wife is also a wildland firefighter. With four kids between the ages of three and eight, they rely on her mother to watch them when both parents are called to a fire or working odd hours. In 2021, staffing shortages forced Corwin to spend 63 days on the Dixie Fire in California before returning home.

Chris O'Brien

Chris O'Brien is the fire chief of the Lefthand Fire Protection District, just outside Boulder, Colorado. He oversees a team of 44 volunteers, most of whom are qualified to be dispatched across the state or nationally as needed when wildfires ignite. (As chief, O'Brien is paid, as are two captains.) The crew also responds as other fire departments do—to structure fires, emergency medical service calls, and motor vehicle crashes.

O'Brien has worked in fire since 1989, when he was in his mid-twenties. Since then, he says, everything has changed. "Fire season is definitely longer than it used to be. And the fire behavior is definitely far more intense." He points to the October 2020 Calwood Fire as an example. The monster blaze swallowed nearly 10,000 acres in just under four hours, and over a dozen structures burned to the ground—a pace and scale of destruction that was unlike anything he had ever seen. It quickly became one of the costliest wildfires in Colorado history, causing about $37 million in damage. "We keep on eclipsing all of these fires annually," he says.

Madison Whittemore

A sewing machine may be the last thing you expect to see on a smoke-jumper base, but these elite wildland firefighters are required to learn how to sew. That's because they have to fabricate their own Kevlar jumpsuits, packs, and parachute accessories so they can withstand unusually rough terrain and hard landings. Smoke jumpers parachute into remote wildlands to provide an initial fire response and ideally prevent it from growing into an out-of-control conflagration. There are nine smoke-jumper bases across the US and around 400 smoke jumpers in the country. Only six are women.

One of them is Madison Whittemore, a former competitive dancer who was hired as a smoke jumper in 2018 in Missoula, Montana. Her dad, a career firefighter, suggested she try it. In the past five years, Whittemore has jumped 130 times, 30 of which were into fire zones.

"I always knew I loved the outdoors, but it [smoke jumping] felt like it was giving me an opportunity to push myself and see what I was capable of in ways that I just hadn't been pushed before. It just kind of gave me a purpose," she says. "Strength became the new pretty, and it was a much more gratifying thing to achieve."

The Coffee Creek Correctional Facility fire crew cuts a line in Oregon.

The Magazine of The Sierra Club

The Magazine of The Sierra Club