Meet the Mainers at the Bleeding Edge of the Home Electrification Revolution

Progressive state incentives, plus the IRA, allow Maine to install heat pumps faster than any other state

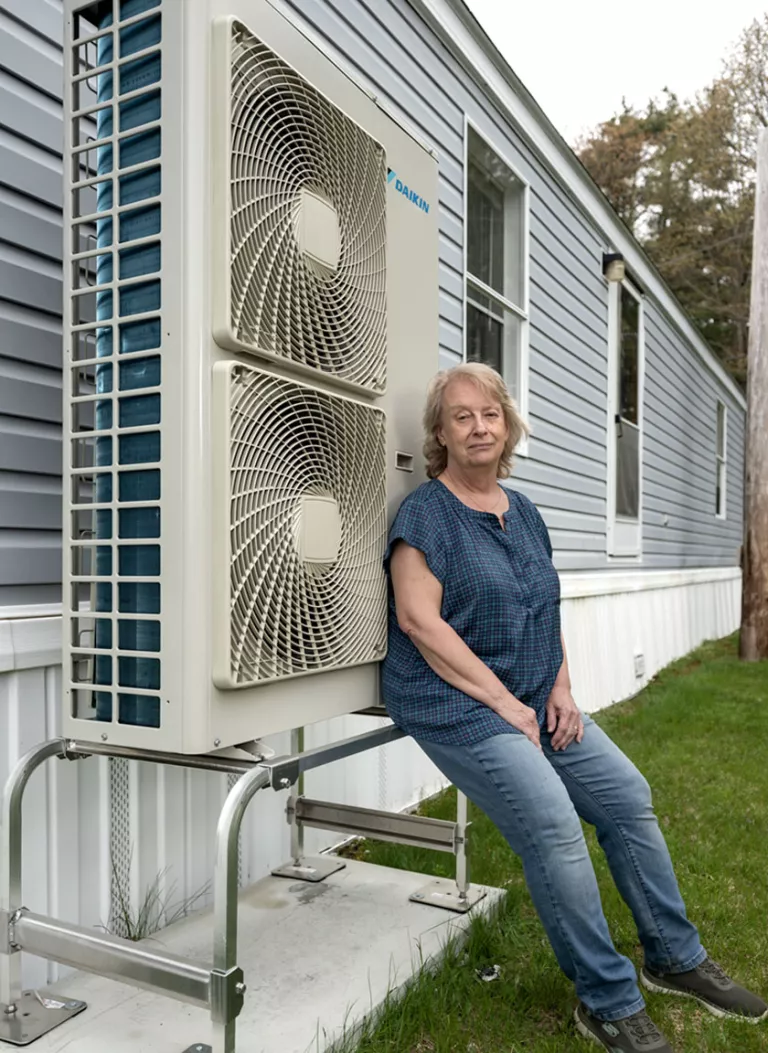

Anne Pappas installed her heat pump through Maine’s incentives for low-income homeowners. | Photo by Séan Alonzo Harris

THE FIRST INDICATION of the home electrification revolution in Maine was a yard sign with a phone number advertising “Heat Pump Cleanings!” just moments after crossing the state line. Condensers hung from many houses like rectangular barnacles. Residents in this state are installing heat pumps three times faster than the national average.

One of them, powered by community solar, is attached to Anne Pappas’s mobile home in Brunswick. It replaced a kerosene heater that had filled her lungs with pungent vaporized gas for 29 years—nauseating her, she said. Pappas’s late husband, John, who died in 2022, had wanted her to “be set up with certain things before he left,” she said. “One of those things was a heat pump.” She got one in February, after receiving a mailer informing her of attractive incentives for low-income homeowners.

In 2019, Democratic governor Janet Mills signed a bipartisan bill calling for 100,000 new heat pumps in Maine homes by 2025. The bill ramped up preexisting incentives from the quasi-governmental agency Efficiency Maine, available a decade before those from the federal Inflation Reduction Act. Mainers now get to double-dip, which doesn’t hurt heat pumps’ popularity. Pappas’s machine now moves air—cool or warm—through ducts under the house and up through vents, one of which is hidden under a chair she reupholstered with fabric from her days stitching flannel sleepwear for L.L.Bean. The old kerosene tank, capped, sits under her front steps like a vestigial organ.

Maine met its heat pump goal two years early and is now aiming for 175,000 more installations by 2027. That would bring the total up to 320,000 heat pumps in a state with only about 580,000 year-round homes. Another bill signed by Governor Mills calls for Maine’s electrical grid to run on 100 percent renewable energy by 2040. As of 2022, it was already at 64 percent.

Staying warm during Maine’s long winter has historically required fossil fuels or a big woodpile, but at least in the short summers, passive sea breezes were enough to cool coastal houses. The forests that cover 90 percent of the rest of the state offered natural temperature control inland. But now the Gulf of Maine is among the fastest-warming bodies of water on Earth, and residents like Frank Barley increasingly rely on air conditioning.

Over the din of a crew of five technicians from Northeast Heat Pumps installing a heat pump system in his house in May, Barley said he used to use window air conditioning for three days a year, but “now we’re running it for 30 days or more during the summer. We wanted to have a more efficient way to cool the house.”

The technicians working in his 1980s Cape Cod–style home made quick, clean work of drilling holes, snaking refrigerant lines through them, adding drains and electrical conduits, and connecting external condensers to indoor ductless evaporators. The new system replaced a woodstove as his primary heat source too. Barley is retiring next year, he said, and wants to do more winter and spring travel without needing to hire a house sitter to stoke the woodstove so his pipes don’t freeze.

Jake Richardson, the systems design specialist at Northeast Heat Pumps, stood in Barley’s backyard, overseeing the installation and swatting blackflies. “I’m totally the guy who grew up burning wood, driving the big truck, and everything,” he said, as his crew pulled a brand-new Fujitsu condenser out of its box. “But I drive this electric truck now. I heat my home with heat pumps. I have solar. I never thought I’d be at this point.”

Efficiency Maine has made fierce heat pump advocates out of customers and technicians by investing in educational outreach and workforce training. But despite Mainers’ rapid uptake of this new technology, there are still skeptics. When Pappas’s son-in-law found out that Efficiency Maine would require her to cap her kerosene tank and get rid of her furnace to qualify for its incentives, he asked what she would do for a backup. Pappas leaned over her oak kitchen table as she recounted her reply. “What did I have for a backup when I just had my furnace?” she said. Her mouth took the shape of a wry New England smile—a flat line, barely curved up at the edges.

There’s still a long way to go. While Maine leads the nation in heat pump installations, it’s also the nation’s top consumer of home heating oil and the second-ranking user of wood-derived fuels. Change is happening, but it’s a big boat turning slowly. Twenty years ago, more than 75 percent of homes were heated with oil, compared with 59 percent today, according to Michael Stoddard, executive director of Efficiency Maine. For now, most heat pumps run in part on electricity generated by methane gas, but they use energy more efficiently than the systems they replace.

“Switching to heat pumps, even with the grid as currently powered, is a significant improvement on carbon emissions and other pollutants, so we don’t want to make the perfect the enemy of the good,” Stoddard said. “That investment that somebody might make in 2024 or 2025 is not only going to improve the pollution footprint immediately, but it will get continuously better with every year that the grid gets cleaner.”

If you ask for directions in Maine, you’ll be told, “You can’t get there from here.” The rural state’s lack of intersecting roads makes some big trips impossible. In contrast, the state’s long journey to a fossil-fuel-free destination is in sight because of many incremental connections along the way. One family plugs more electrical systems into a partly renewable grid. They tell their neighbors to try it out. A farm down the road hears about the need for more renewables and leases its land for community solar generation. Then one day it all comes together, and you’ve arrived.

The Magazine of The Sierra Club

The Magazine of The Sierra Club