Abolish Fossil Fuels

A moral case for ending the age of coal, oil, and gas

AFTER A LIFETIME of liberal activism, Elizabeth Heyrick was feeling depressed. Heyrick in her time was one of the most influential and uncompromising opponents of slavery in the British Empire, and she knew all too well the political obstacles she and her fellow abolitionists faced. Although historians don’t know what drove her to despair in the last years of her life, it very well may have been the feeling that “the sentiment of the abolitionists” seemed “hopeless.” In a private letter to a fellow abolitionist, she wrote, “Nothing human can dispel that despairing torpor into which I have been plunging deeper and deeper for many months.”

Today we would call Heyrick an intersectional activist. A former schoolteacher and a Quaker convert, she authored pamphlets arguing for electoral reforms and the rights of the working class as well as booklets against capital punishment and animal cruelty. Her most famous tract was an essay, published in 1824, titled “Immediate, Not Gradual Abolition.” She blasted the male-dominated abolitionist establishment for its timid pursuit of a slow-motion eradication of slavery—“the spirit of accommodation and conciliation has been a spirit of delusion”—while making an impassioned case for complete emancipation. “Truth and justice make their best way in the world when they appear in bold and simple majesty; their demands are more willingly considered when they are most fearlessly claimed.”

Heyrick died in 1831 at the age of 62. Just two years later, the once remote and seemingly hopeless cause of British abolitionism succeeded. In 1833, Parliament passed the Slavery Abolition Act, which eventually emancipated more than 800,000 enslaved Black men, women, and children throughout the empire. An act of law—driven largely by grassroots action—had eradicated a great evil.

The story of social change is full of surprises. People’s movements often agitate for what can feel like forever—years into decades, decades into generations. Then victory comes swiftly. When Heyrick was born in the 1760s, much of humanity lived as prisoners, not just in the Americas but across the Ottoman Empire, throughout the baronial plantations of Russia, and in India, where debt peonage chained tens of millions. Less than a century later, slavery had been abolished in the United States, and serfdom in Russia too. Slavery would soon come to an end in Brazil. Enslaved peoples’ demand for freedom—joined with the solidarity of people of conscience—opened the door for truth and justice to make their way in the world.

Today those of us in the movement for climate justice find ourselves in a position similar to that of the abolitionists in the early 19th century. We too are engaged in a great moral struggle, with the fate of generations hanging in the balance. We too confront impossible odds, with all the power and wealth of mighty corporations piled against us. History, though, is our ally. It can help us to see our present plight more clearly and sharpen our imaginings of the future. Through the experiences of abolitionists like Heyrick, we might discover consolation and inspiration, tactical instruction even.

There is, of course, no analog to slavery, which is singular in its depravity. It would be perverse to make a direct equivalency between the cruelty of chattel slavery and filling one’s gas tank. But even though history doesn’t repeat itself verbatim, the rhythms of the past do sometimes echo.

If the abolitionists have anything to teach climate-justice advocates, it’s a lesson in the necessity of making a political demand that is clear-eyed, radical, and unapologetic. “Power concedes nothing without a demand,” abolitionist and former slave Frederick Douglass famously said in an 1857 speech. “It never did and it never will.” The abolitionists didn’t seek to merely ameliorate or restrict slavery—they sought to eliminate it. They understood the moral clarity of zero.

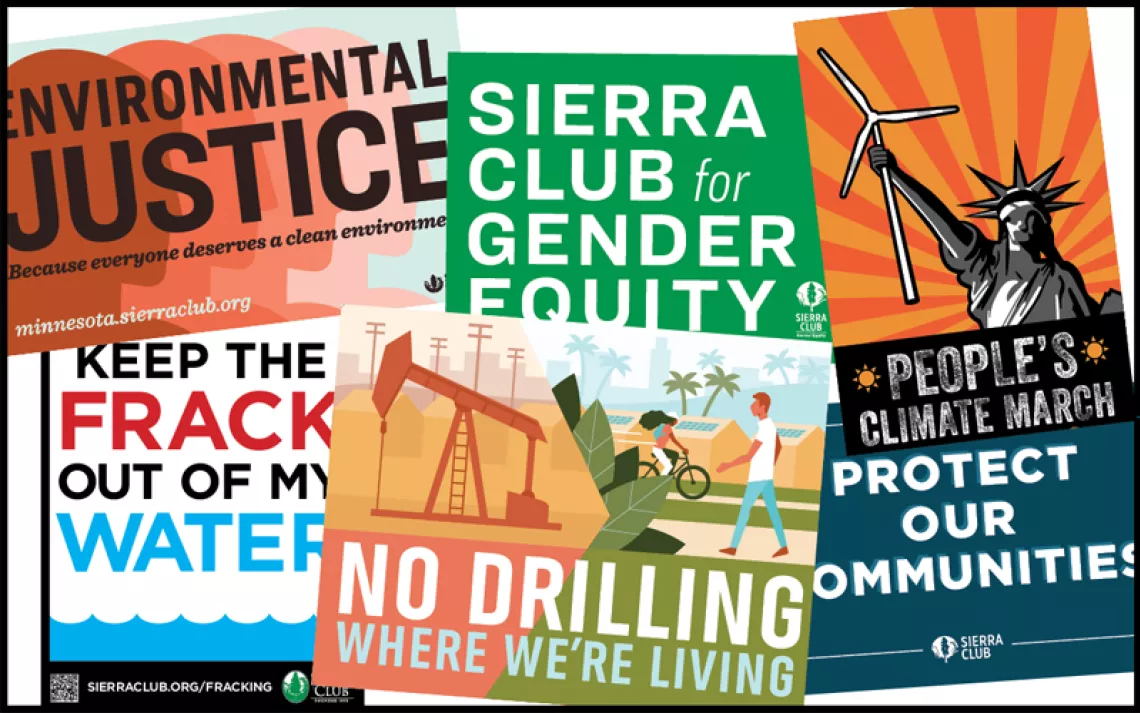

The movement for climate justice has, similarly, understood for many long and increasingly hot and storm-tossed years that civilization must halt the use of coal, oil, and gas to preserve the well-being of the planet and its communities. Millions of people around the world have marched to “end fossil fuels.” Some have thrown their bodies against the gears of the extractive machine to demand that oil and gas stay in the ground. “Stop burning things,” author-activist Bill McKibben has urged.

The arguments for eliminating our use of fossil fuels are strong and straightforward. We know that industrial society’s combustion of coal, oil, and gas is dangerously heating the planet. We know fossil fuels cause death and destruction. We know, therefore, that if we want to halt global temperature rise and the damage that comes with it, we must leave most of the known fossil fuels in the ground. We also know that we have the renewable energy technologies to replace dirty and dangerous energy. As a movement, we need to take those arguments to their logical conclusion.

Have we made it perfectly clear to the rest of the public that what we seek is the elimination of fossil fuels? Have we communicated the moral necessity of zero?

Sign up to receive Sierra News & Views

Get articles like this one sent directly to your inbox weekly.

With this action you affirm you want to receive Sierra Club communications and may vote on policy designated by the Sierra Club Board.

Our North Star must be unmistakable: the abolition of fossil fuels in our lifetime.

THE MOST OBVIOUS parallel between the abolitionist movements past and present is the most sobering: the awesome force of the powers fueling the status quo. In his essay “The New Abolitionism,” published in The Nation a decade ago, broadcast journalist Chris Hayes compared the political and economic power of 19th-century enslavers to that of the fossil fuel industry in the 21st. On the eve of the Civil War, the market value of the humans held in bondage in the United States was some $10 trillion in today’s dollars. The global oil and gas industry is worth at least twice that. If you take climate science seriously, Hayes wrote, “you must confront the fact that the climate-justice movement is demanding that an existing set of political and economic interests be forced to say goodbye to trillions of dollars of wealth.” (Though even when we eliminate fossil fuels as an energy source, some smidgen of hydrocarbon extraction may prove necessary for the manufacture of durable plastics and the fabrication of the synthetic fertilizers that currently sustain global crop yields.)

Two hundred years ago, abolitionists confronted what they called the Slave Power—the network of businessmen, newspapermen, and political men who defended the lucrative status quo, and whose influence stretched all the way to the Supreme Court. Today we confront the Carbon Barons—the individuals and corporations that use their wealth to buy airtime and purchase politicians and judges to maintain the fossil fuel era. In its time, the Slave Power dominated global trade: sugar, cotton, shipping, bodies. The Carbon Barons are even more powerful. Fossil fuels take our daily bread from field to table. They deliver our clothes—increasingly synthetic and derived from fossil fuels—from factory to outlet mall. In most places, they are still essential to keeping our homes, businesses, and houses of worship lit. Fossil fuels drive the planes, trains, and automobiles that speed us around. Fossil fuels provide nearly 90 percent of all the power Americans use. They are the weft and weave of modern society.

Our North Star must be unmistakable: the abolition of fossil fuels in our lifetime.

But just as the antislavery abolitionists did, we can widen the cracks in the status quo. The opponents of slavery knew that, in their time, nearly every free person was complicit in slavery’s violence: “It is a question in which we are all implicated,” Heyrick wrote, referring to white Britons. This also meant, though, that every ordinary person had some ability to land a blow against the enslavers by making “an irrevocable vow . . . to participate no longer in the crime.” The British abolitionists of the late 18th and early 19th centuries did this by boycotting sugar, most people’s clearest connection to an odious system. Then, as today, the cynical scoffed at such efforts. Heyrick had a response: “What can the abstinence of a few individuals, or a few families, do? It can do wonders. Great effects often result from small beginnings.”

Two centuries later, we know that every joule of fossil fuel energy avoided by conservation or replaced by wind and solar helps to unravel the power of the Carbon Barons. The bike trip to the grocery store, the rooftop solar installation, the weatherization of windows, the purchase of an electric vehicle, the one-liner written on the placard carried at the climate march—each of these actions helps, like the sugar boycott, to shift the terrain of the possible. “Your resolution will influence that of your friends and neighbors,” Heyrick argued. “Each of them will, in like manner, influence their friends and neighbors; the example will spread from house to house, from city to city.” This is confirmed by 21st-century social psychology. Rooftop solar is contagious: When one household on a block puts up an array, the neighbors are more likely to do so. Every long march is made up of countless simple steps.

Beyond the issues of political economy, past the questions of individual and collective agency, lies another similarity between the abolitionist movements of past and present: the ways in which oppression degrades the spirit of people who find themselves complicit in it. The enslaved knew this better than anyone. “Surely this traffic cannot be good, which spreads like a pestilence and taints what it touches,” wrote Olaudah Equiano, a formerly enslaved person whose autobiography became an 18th-century bestseller and who was a major voice in the British abolitionist movement. Many of us who have committed ourselves to climate justice have felt how our daily collusion in climate change can create a spiral of guilt and shame that might, in Equiano’s words, “harden [one] to every feeling.”

Our dependence on fossil fuels works like a chain link. To maintain our lifestyle of convenience, we’ve swapped human labor for the labor of machines that run on fossil fuels—what Buckminster Fuller called “energy slaves.” According to one estimate, every American has something like 600 energy servants; even the poorest among us have a retinue of fossil energy. We are yoked to fossil fuels—golden handcuffs, greased with petroleum.

To abolish fossil fuels, then, would be an act of collective liberation. And that liberation—whenever it comes—will ripple outward into the future. Perhaps the most profound similarity between these abolitionist movements is the vastness of the stakes involved. The antislavery abolitionists knew that they were demanding not simply the freedom of those enslaved in their era but also freedom for people yet unborn. Generational liberty was on the line. Our movement for climate justice is, likewise, a movement for intergenerational justice. We seek to be good future ancestors by preserving the best of today for eras still to come. Whatever we can do to preserve the climate in a semblance of stability is a gift to the future.

The abolition of fossil fuels is an act of solidarity across the fields of time.

HERE ARE THE FACTS of our present situation.

Fossil fuels kill people. The numbers vary, but public health researchers estimate that around 7 million people across the planet die prematurely every year due to the air pollution (mostly particulate matter) fossil fuels generate. By comparison, globally about 7 million people have died from Covid. Every year, fossil fuels kill on the order of a pandemic.

Climate change caused by the burning of fossil fuels then piles additional deaths onto the scale. According to a researcher at the Georgetown University School of Medicine, global warming has already killed 4 million people since the turn of the century due to floods, diarrhea, and malnutrition associated with extreme weather and failed harvests. The World Health Organization forecasts that climate change impacts will cause approximately 250,000 additional deaths annually by the 2030s.

On top of killing people by the millions, the Carbon Barons’ status quo is robbing us of trillions of dollars. In the first 20 years of this century, extreme weather events like hurricanes and floods caused about $2.8 trillion in damage. In 2022, climate-change-intensified flooding in Pakistan drove 8 million people from their homes. Earlier this year, unprecedented floods in southern Brazil displaced 600,000 people. Without the abolition of fossil fuels, the dangers will only worsen. A paper published last spring in the journal Nature estimated that by 2049, climate change effects on agriculture, labor productivity, and infrastructure will eat up as much as $38 trillion annually—that’s a fifth of the global economy incinerated to keep the fossil fuel fires burning.

In response, the Carbon Barons and their apologists attack the methodology of weather attribution. They argue that it’s impossible to link any single rainstorm to fossil fuel use. But there’s no arguing that there is a connection between fossil fuels, the greenhouse effect, and lethal heat waves. Last year, extreme heat in metro Phoenix killed at least 645 people—nine times the number of annual deaths just a decade earlier. Some 1,300 Muslim pilgrims died from heat exposure during this year’s Hajj to Mecca. Extreme heat is the perfect lie detector for climate misinformation; fossil fuels’ fingerprints are all over the autopsies.

When pressed with the evidence of climate change’s death and destruction, the Carbon Barons and their functionaries say, in effect, that the wealth and well-being created by fossil fuels are worth it. They are correct that abundant energy has created a world of wonders: light with the flick of a switch, heat or cold with the turn of a dial, all the entertainments of the internet, effortless mobility. Thanks to boundless energy, billions of people live lives of historically unimaginable privilege. But in the mid-2020s, the Carbon Barons’ cost-benefit argument crumbles for a simple reason: Fossil fuels are no longer necessary to deliver the abundant energy we’ve come to rely on.

If you want to abolish something, make it obsolete. We are at that tipping point with fossil fuels.

If you want to abolish something, make it obsolete. We are at that tipping point with fossil fuels. Countries as dissimilar as Costa Rica, Iceland, and Norway are now getting almost all their electricity from renewable sources. During some portion of nearly every day this past spring, California generated more energy from wind, solar, and geothermal sources than the state needed to meet its total electricity demand. Globally, solar energy development is increasing at an exponential rate. The growth curve is nearly vertical, like a ladder leading to that massive ball of fusion energy in the sky.

In attempting to defend the continued use of fossil fuels, the Carbon Barons confuse inputs for outputs. It’s not fossil fuels that civilization needs; it’s energy. Most people just want speedy wi-fi, comfortable homes, and fast transportation—they don’t much care where the power comes from.

With substitutes for fossil fuels at hand, the apologias for coal, oil, and gas fall apart. Fossil fuels’ demonstrated harms are inexcusable because they have become avoidable. The benefits of abundant energy can’t justify the death and destruction from fossil fuels—not when energy can be had from sources that don’t involve that same daily damage.

The end of the fossil fuel era cannot come soon enough. It’s equally true that this vast industrial transition will be—contra Heyrick’s bold radicalism—more gradual than immediate. We are too enmeshed in fossil fuels to break our reliance on them overnight. As a matter of justice to those who are still living in energy poverty—as a matter of fairness to the working families whose paychecks are hitched to fossil fuels—this will have to be a steady, deliberate elimination. In the near term, a plateau. Eventually, a deceleration. Ultimately, a complete halt.

ELIZABETH HEYRICK described slavery as “wealth obtained by rapine and violence.” The continued extraction and combustion of coal, oil, and gas is another form of calculated violence in the pursuit of wealth. It’s violence against the lungs of anyone who has to breathe in the soot from smokestacks or the smog from tailpipes. It’s violence against the atmosphere that sheaths the planet. And it’s therefore violence against every living creature that depends on that atmosphere.

Beyond the intergenerational sweep of climate advocacy, the efforts of today’s fossil fuel abolitionists are also imbued with the moral calling of interspecies solidarity.

We do this work on behalf of all the other life-forms with whom we have always shared this planet, and whose well-being is every bit as endangered by fossil fuels as ours is. We demand the abolition of fossil fuels in the memory of the 1 billion sea creatures that broiled to death during the Pacific Northwest heat dome of 2021—an event all but impossible in the absence of climate change. We call for the end of fossil fuels to protect the pika and the ptarmigan, species already at the upper ranges of their habitats, with eventually nowhere left to go. We insist on a halt to fossil fuels because these species have an intrinsic right to exist and to thrive—just like us.

Such a calling is frighteningly ambitious. Once again, the long view of history delivers a consolation. British slavery was 276 years old when it died. From the arrival of the first enslaved Africans in the American colonies to the end of the Civil War, 246 years passed. It’s now been about 260 years since the commercialization of the steam engine. By the measure of past people’s movements, we are due—if not overdue—to achieve the abolition of fossil fuels.

We cannot know, of course, when that victory will come. We do know that, like Heyrick, we may not live to witness it. It doesn’t matter. What matters is that we strive. “It is not always granted for the sower to see the harvest,” the 20th-century humanitarian Albert Schweitzer once said. “All work that is worth anything is done in faith.”

Do we have the faith to believe that when action is welded to commitment, it can move the whole world? Faith is a form of imagination, so imagine it all. How we’ll breathe more easily when fossil fuels are no more. How we’ll no longer be tethered to the profit-mad Carbon Barons, since the sun gives away its power for next to nothing. How other species will be liberated, in some measure, from human recklessness.

The North Star of fossil fuel abolition is fixed. There are no more defensible justifications for the indefinite continuation of the age of coal, oil, and gas. There are no good reasons left for delay. We are ready to cut ourselves loose from fossil fuels, and when that happens, we’ll gasp with freedom. For Earth and all its inhabitants, the end of fossil fuels will be an emancipation.

Correction: The original version of this essay inaccurately stated that Namibia gets almost all of its electricity from renewables.

The Magazine of The Sierra Club

The Magazine of The Sierra Club