Two Coal States, Two Very Different Futures

Colorado and Montana both depended on coal, but only Colorado admits that it's over

The Colstrip power plant, which Montana's state government is trying to keep open, and Main Street in Nucla, Colorado, which is moving on from its long history with coal.

AS THE SUN rose on July 23, 2021, a sudden, sharp crack echoed across the high desert on the outskirts of Nucla, Colorado. Flickers of light snaked up the support beams holding what was left of the Nucla Station power plant's Unit Four. Black clouds poured from the building's base. Within five seconds, it collapsed in a rolling roar of sound and smoke, and then the 215-foot steel stack next to it toppled into the ruins. Tri-State Generation and Transmission had finished the demolition of the first of its four wholly owned coal-fired power plants. You might say that the era of coal in the West End of Montrose County ended with a bang.

For decades, Nucla Station and the source of its coal, nearby New Horizon Mine, had formed the backbone of the West End's economy. They provided well-paying union jobs in a remote region where other options were slim and pumped property taxes into the little towns of Nucla, Naturita, Norwood, and Paradox. When the plant and mine shut down in 2019, their closures triggered an economic tumult that the communities are still reckoning with today.

About 500 miles north, the Crow (Apsáalooke) Tribe of south-central Montana grapples with a similar situation. There, too, coal has propped up the economy. But the tribe's coal mine has been in steep decline for the past nine years. Another nearby mine closed in 2021, and Montana's largest power plant, coal-burning Colstrip, retired two of its four units in 2020. On a reservation already struggling with poverty and unemployment due to the cumulative effects of colonization, coal's downward spiral threatens further suffering.

There's a key difference in the way Colorado and Montana are handling their transitions away from coal. Colorado is putting millions of dollars and a first-of-its-kind state administrative office toward helping coal communities shift to new, sustainable, diversified futures. Montana, on the other hand, is clinging to coal so tightly that any talk of transition is seen as betrayal, leaving its coal regions on their own.

As methane gas and renewable energy sources have become much cheaper, and environmental regulations have restricted carbon emissions, coal production nationwide is half what it was in 2008. Its crash has evaporated tens of thousands of coal jobs from West Virginia to Alaska. While that's undoubtedly good news for the climate, every shuttered mine and power plant means more employees who need to find another way to feed their families. It means more towns that lose the funds they relied on for schools, libraries, and fire departments.

The Colstrip power plant.

As the global energy transition takes hold, ensuring a just transition grows in importance. The International Labour Organization defines the concept as "greening the economy in a way that is as fair and inclusive as possible to everyone concerned, creating decent work opportunities and leaving no one behind." That can mean job retraining, thoughtful community development, and, ideally, money to help those affected get back on their feet.

The people of coal country—former miners and power plant workers, construction workers, mom-and-pop business owners—face profound transformations of their daily lives. How they come out may depend on what state they live in.

ONE LATE-SUMMER DAY in 2016, Roger Carver squeezed into the training room at Nucla Station with all the other employees of the power plant and New Horizon Mine. A day or two before, Tri-State had announced a company meeting. Carver knew what that meant.

Carver has lived his whole life in Nucla, and his family history in the West End and in mining stretches back to the early 1900s. His grandfather worked a string of pack mules that hauled uranium ore from the area's mines to the freight train in nearby Placerville. His stepfather worked in the local Peabody strip mine in the '70s. Carver himself had been mining coal for 24 years, and at that time in 2016 was the president of his United Mine Workers local.

At the meeting, Tri-State's top brass announced that they would be closing both the mine and power plant by 2022. "We'd seen things coming for quite a while," Carver says, "but a lot of guys didn't. They thought Trump was going to save them." Carver was 57 at the time, fighting lung problems and close to retirement, so the news didn't drastically change his plans. But by the following June, Tri-State had sped up the timeline, and the mine permanently ceased coal production. Nucla Station also ceased operation in 2019, three years ahead of schedule. "A lot of people got a real shocker," Carver says.

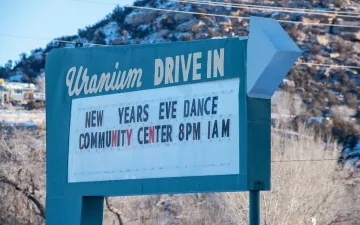

That wasn't West End's first mining boom-and-bust. The region had been a hub for mining and milling uranium and vanadium from the 1940s to 1984, famously supplying the Manhattan Project. In 1986, the whole operation was declared a Superfund site, and the EPA completely demolished and buried the town of Uravan, 18 miles northwest of Nucla, over radiation concerns. That left coal mining and the power plant as the West End's economic drivers.

Any community dependent on coal is a community at risk of collapse, as the remains of former American boomtowns rooted in logging, gold mining, and steel manufacturing can attest.

That foundation began to crumble in 2012, when a lawsuit from the environmental group WildEarth Guardians over regional haze rules successfully compelled Tri-State to retire Nucla Station, New Horizon Mine, and another coal-fired generating unit in northern Colorado. As coal power grew more and more expensive and the utility embraced a low-carbon plan (in keeping with Colorado's ambitious emission-reduction goals), Tri-State moved up its deadline.

"We could've used those two years," says Aimee Tooker, a Nucla entrepreneur who serves as president of the West End Economic Development Corporation. "We lost a lot of young families." Many of the laid-off workers took jobs at Tri-State's coal plant in Craig, Colorado, 250 miles away, only to face the same situation in 2020 when the utility announced it would close that facility too, within the decade. Others took early retirement or stayed put and found new jobs with a big pay cut. The closures meant a 67 percent loss for the West End's property taxes, which funded the area's schools, fire department, and cemetery district. "That was a pretty big blow," Tooker says.

Morale in the community plummeted. "As we transition away from fossil fuels, the side effects are crushing to communities like this," says Brock Benson, who was born in Nucla to parents who worked for the Peabody mine. "Mining built these communities. But the economic fallout of all of it going away—that's devastated them."

BILL YELLOWTAIL lives in what he calls the Apsáalooke heartland, on the shoulders of the Big Horn Mountains just this side of the Wyoming border. "Crows have always treasured that area because it's so verdant," he says. "When it's 100 degrees down here in the lower valley, up there it'll be 75. We have wild fruit, and wild game, and wonderful clear water." Yellowtail's great-grandfather claimed the land when the federal government divided up tribal lands for individual ownership. "That landscape has a great depth of meaning for me," Yellowtail says. "I have this sense that Yellowtails have been there a very long time."

Main Street in Nucla, Colorado.

To others, the Apsáalooke heartland is the Powder River Basin, a grassy, big-sky landscape stretching across southeastern Montana and northeastern Wyoming that's incredibly rich in coal deposits. More than 40 percent of the country's coal is pulled from the earth right here. The Crow Tribe's economy has been knotted to mining for decades, thanks to its 9 billion tons of coal reserves. "We are addicted to coal here," says Yellowtail, who served as a regional administrator at the EPA during the Clinton administration, "even to the extent that we don't object to tearing vast holes in Mother Earth. Our old ethic from my great-grandfather's time would have objected strenuously. Now we don't think twice about it. Our dependency runs deep."

Though both the Crow Nation and the Colorado coal communities have relied economically on the same fossil fuel for decades, their situations aren't parallel, for reasons both historical and structural. After smallpox epidemics killed 80 percent of the Apsáalooke population by the middle of the 19th century, the US government chipped away at the tribe's homeland until just a sliver remained. In 1851, the US formally recognized 38 million acres across what is now Montana and Wyoming as Crow territory; today only 2.3 million acres remain. By the 1880s, the nomadic seasonal hunters were pushed into an agricultural life on their reservation, the plains bison were being slaughtered, and white settlers were encroaching on what little was left of their land. Forced assimilation through government policy, including abusive boarding schools where children were stripped of their culture, left a legacy of trauma within a nation that today still very much values and practices its language and traditions.

The Crow Tribe's coal reserves are especially key because the Crow government, like that of most other Native nations, doesn't collect property or income taxes. It does, however, collect severance taxes and royalties from Westmoreland Resources, which has been leasing Absaloka Mine and extracting the tribe's coal since 1974. The mine lies just outside the reservation's northern boundary, on a piece of land the federal government took in 1904; legislation in the 1950s affirmed the tribe's mineral rights there. Spring Creek Mine, 130 miles south, also provides high-paying jobs to tribal members. But it's Absaloka that feeds the tribe's coffers most. Coal makes up at least 75 percent of the tribal government's budget.

"Other counties and cities rely upon a tax base to generate the revenues that support the development of their community or the delivery of public services," says Lesley Kabotie, a Crow tribal member and secretary of the board of the three-year-old nonprofit Wyola Development Fund, based in the tiny town of Wyola on the reservation's southern border (Yellowtail, her cousin, serves as chair of its board). "Tribal economies don't have the benefit of that. As a result, our economies don't have a steady flow of recurring revenue. What we have is the sale of nonrenewable resources."

"Dreams are just dreams until you wake up and put some muscle in to change your situation."

The Crows' coal resources have been buffeted by the same energy transition that's taking place in Colorado. Decker Mine, just east of the reservation boundary line, shuttered in 2021, taking more than 100 jobs with it. The owners of Spring Creek Mine filed for bankruptcy in 2019. After new owners revived a proposed expansion, a federal judge struck it down in 2021. And Absaloka Mine's output has been in free fall: In 2022, it produced 2.2 million tons, a third as much as in 2014.

The tribe's income fell in step. From 2015 to 2019, tribal coal income decreased by as much as 80 percent. Tribal government, one of the top employers on the reservation, has had to lay off workers. Funds earmarked for support projects across the Crow Nation's six districts vanished. And per capita payments to tribal members declined significantly.

"When coal started phasing out, you could see the impact right away," says Roberta Glenn, who worked in children's mental health and business education for the Crow government at the time. "You could see the need greatly increase with the funding shortage. Food was an issue. Crime went up. Unemployment rates on the reservation are extremely high." (The US Census Bureau reported a nearly 30 percent poverty rate on the Crow Reservation in 2022.) Many have had to leave to find work elsewhere.

Despite the plummeting coal production of recent years, there's not much of a plan B for the Crow Nation right now. (Crow tribal executive leadership did not respond to interview requests.) "We cannot seem to grasp the inevitability of the decline of coal," Yellowtail says. "In my estimation, it will go away. I think Crow tribal government will starve to death. And we'll be left without."

ANY COMMUNITY dependent on coal—or any single industry—is a community at risk of collapse, as the remains of former American boomtowns rooted in logging, gold mining, and steel manufacturing can attest. Experts say that the best way to transition out of a coal dependency is to diversify the economy, something made far easier with the assistance of state and federal governments.

"A lot of our leaders will say they had all their eggs in one basket," says Grace Blanchard, who manages programs for resilient economies and communities for the National Association of Counties. "We're looking to empower communities to have their eggs in multiple baskets."

How to transform a place dominated by a single employer into a thriving mix of small businesses, renewable energy projects, and other ventures that won't take the whole town down with them if they fail? Cash helps—to hire transition consultants and grant writers, to fix aging infrastructure and build new residential and commercial spaces, to develop outdoor recreation and tourism amenities. Often, that means piecing together funding from a slew of sources: federal grants, state programs, tax incentives, philanthropic donations, and community nonprofits.

A revamped miner's cabin at CampV, a glamping/arts center in a former Colorado coal town.

Such planning requires strong partners in government, says Teryn Zmuda, chief economist for the National Association of Counties. "Intergovernmental coordination is really key to any successful implementation of programs," she says. "County-to-state and county-to-federal, those are really critical partnerships. We want all our stakeholders at the table, having conversations and buying in." But that requires having willing higher-level officials to work with—like those in Colorado.

TANYA NARRAMORE also learned that she was out of a coal job at that Nucla Station meeting in 2016. A lifelong resident of the West End, she had been working at New Horizon Mine for 19 years, driving 100-ton haul trucks. She had plenty of working years ahead of her and considered transferring to the Craig coal mine. "But I just couldn't bring myself to do it," Narramore says. "I figured coal was going to be nonexistent before too long." She applied to work for the Montrose County Road and Bridge Department but was turned down because she didn't have a commercial driver's license.

Fortunately, the first influx of just-transition cash was reaching the West End from the job-promoting Markle Foundation. It paid for a workforce-development program called Skillful West End at the end of 2018, hiring local Carla Reams to help manage the transition. Reams visited the power plant and the mine, offering to help employees with job retraining, résumé writing, and job searches. Narramore was one of the many who took her up on it. With Reams's guidance, Narramore went to truck driving school, earned her Class A license, and reapplied with the county.

Narramore landed the job. She's had to get used to a significant pay cut, but she likes the new gig and the fact that it's only four miles from home. Tri-State also kicked in $500,000 for the community through the West End Pay It Forward Trust, which has funded nonprofit programs, including suicide prevention, as well as an ATV for the search and rescue team and new siding for a community building in Paradox.

Much more money soon followed. During the 2019 session, the Colorado legislature created the Office of Just Transition (OJT) within the state Department of Labor and Employment—the first of its kind in the country. (The Sierra Club's Colorado Chapter played a major role, along with unions in the BlueGreen Alliance, in passing a just-transition bill.) "This was incredibly necessary, because we know our economy is changing," says Senator Faith Winter, a Democrat who represents Denver's northwest suburbs and was one of the bill's sponsors. "There are winners and losers. And we need to ensure that we're taking care of our workers and our communities that have relied on coal." In 2022, the legislature voted to stock the OJT with $15 million from the state's general fund. That money went toward the creation of a worker assistance program and to direct grants for eight Colorado coal communities.

The West End's coal workers had already moved on by the time the OJT grants came around, but the community still has priority status. As Tooker puts it, "We've already transitioned, but we haven't recovered." (The 2022 poverty rate, according to the US Census, was 19.4 percent in Naturita and 18.1 percent in Nucla.) A task force of West End leaders decided to focus on major infrastructure projects in order to pave the way for new residents and businesses. "The septic in Nucla and Naturita is pushing 100 years old," notes Makayla Gordon, the executive director of the West End Economic Development Corporation. "Anytime we try to tap into a pipe, it bursts. You can't grow if you can't flush your toilets." The OJT awarded almost $1.75 million to Nucla, Naturita, and Norwood for wastewater system upgrades. Even communities that have not yet lost their coal are spending on economic diversification projects, like developing a boat ramp on the local river and building a new business district.

West Enders have their gripes about the Office of Just Transition—mostly, its requirements for how each round of funding can be spent. "I'd like to see this money more nimbly used," Montrose County commissioner Sue Hansen says. "The communities know what they need." But broadly speaking, people recognize their good fortune. And some expect Colorado's other coal communities will have an easier time of it when their power plants or mines finally shut down, as long as they plan ahead. "I don't think they'll have near the bumps and near the loss that we've had," Tooker says. "They've got the resources now. What they want to get done, they should be able to get done."

Makayla Gordon is working to attract new employers to the West End of Montrose County.

Gordon describes the West End's transition as being in the "marathon phase." Community members have plenty of ideas for how to move forward. Many would like to see a revival of uranium mining; others hope for a new hospital or a solar farm. "We would happily welcome a larger company to come in," Gordon says. "But being able to support three or four smaller employers makes more sense for the community than one larger employer does." There's still a lot of work to be done, and the West End plans to put its next rounds of transition dollars toward building more housing to accommodate growth, maintaining an apprenticeship program, and further developing its tourism potential.

West End's future is already coming into view. An organic grocery store started up in the area in 2019. The region's redrock canyons, high-desert landscapes, and abundant public land support a burgeoning network of mountain biking and ATV trails that attract more and more tourists, and businesses to support them are beginning to arrive. Brock Benson, whose parents worked at the Peabody mine, moved back in 2021 and opened a bike shop, Paradox Cycle, in Naturita in 2022. Even though a combination bike shop and pizza parlor opened across the street from him in 2023, Benson says business at Paradox Cycle is booming. A couple of miles past Naturita, on the site of the former mining-industry company town of Vancorum, Natalie Binder launched a glamping/arts center called CampV in 2021. She found out after she got the contract that her grandparents had lived there during uranium's heyday.

When she first invested, she says, just after the news of the coal closures, "a lot of people were like, 'This community is going away. Why would you do something like that?'" But Binder saw hope and opportunity in the outdoor recreation and new trails, and in the formation of the economic development corporation. "I said, 'I want to be a part of this.' I knew I wasn't going to be going into this alone."

Binder pieced together funding to get her business off the ground. Some of her major investors are part of a federal Opportunity Zone project, which offers tax breaks for investing in economically distressed communities. She's also won grants from the Colorado Office of Economic Development and International Trade's Colorado Creative Industries program, the nonprofit Telluride Foundation, and the West End Pay It Forward Trust. "Honestly, it would've been so challenging, if not impossible, to do a lot of the stuff we've done without some of these granting opportunities," she says.

Roger Carver, a former coal miner, says people were surprised when the local mine closed. "They thought Trump was going to save them."

CampV, with its rehabbed miners' cabins, water-tank stargazing, and dandelion-shaped art installations, has started to become an international draw. "It's interesting to be in a transitional economy," Binder says. "It's a cool opportunity for people to define what the future looks like for themselves and their children."

THE DOOR at Tipi Creek Coffee Co. stood propped open on a warm Monday afternoon last October, leading to a bustling scene on the main drag in Crow Agency—just "Crow" to locals. Several customers got the lunch special, chicken fried rice; others came for ice cream or the rainbow of Lotus energy drinks. One man set up in the front with a laptop, near a large painting of a bison by owner Tana Cummins's brother Ben Pease. "People come in the door and say, 'Jeez, I feel like I've walked out of Crow and into another world,'" Cummins says. "That's what we're trying to do. Coffee, in our culture, it gathers people."

Tipi Creek began as a mobile coffee trailer in 2021, when Cummins, a former teacher, needed a flexible job she could bring her baby daughter to. That's where it would have stayed if Charlene Johnson, director of the Crow Agency's Plenty Doors Community Development Corporation, hadn't offered her a spot in the nonprofit's business incubator. Cummins moved her coffee business to Plenty Doors' building in 2023. With reduced rent and support programs like QuickBooks training, she was able to hire two employees. She shares the building, and the incubator program, with a credit union, a construction business, and an independent news publisher. In the next year or so, Plenty Doors plans to move into a larger building and expand its incubator to six or seven Native-owned businesses.

With coal on the decline, the program is exactly what the Crow Nation needs—a leg up for small businesses to diversify the reservation economy. Still, new enterprises face significant challenges. A major one, says Plenty Doors operations manager Charitina Fritzler, is a dire lack of suitable buildings, both commercial and residential. She wonders what will happen to incubated businesses after they graduate in three years. "Where are they going to go?"

Wyola, Montana, on the southern border of the Crow Reservation, which was hit hard by the decline of the coal industry.

Just-transition funding like Colorado's would be a big help. "It's the difference between starving to death and having access to a buffet table," the Wyola Development Fund's Kabotie says. But the state of Montana continues to cling to coal. During the 2023 legislative session, the state's Republican supermajority passed laws instructing state agencies to ignore greenhouse gas emissions when drawing up environmental reviews and making it easier for coal mines to expand. Governor Greg Gianforte touts an "all of the above" energy policy. And in January 2023, Montana's largest monopoly utility, NorthWestern Energy, expanded its ownership of the Colstrip plant, pledging to keep it firing through 2030, drawing cheers from lawmakers at a reception in a Helena hotel ballroom.

Back in 2019, state senator Denise Hayman, a Democrat from Bozeman, introduced a securitization bill to help retire coal-fired power plants like NorthWestern Energy's Colstrip. But Republicans objected to the bill's just-transition funding, and it was removed. The year before that, the nonprofit Montana Environmental Information Center and the Northern Cheyenne Tribe, whose reservation neighbors the Crow's to the east, both requested coal transition funding in a utility rate case before the Public Services Commission; both were denied.

"The state of Montana is not interested in talking about the future of coal," says Anne Hedges, the environmental center's co-director. "They think that if they pass some kind of bill that would assist with the transition, they're admitting there's going to be a transition. And that is heresy in this world. What they're doing is screwing over coal communities."

"At this point, there's no help for the Crow Tribe," says state representative Sharon Stewart Peregoy, a Democrat from Crow Agency and a tribal member. "And there's no interest to help."

Tana Cummins is exploring a new direction with Tipi Creek Coffee Co., part of an incubator with other Native-owned businesses.

Without support from the state, some members of the Crow Nation are working to diversify the tribal economy on their own. There's talk of reviving the reservation's casino or developing a cannabis industry. Some want to see solar or wind projects, like the commercial solar farm the Northern Cheyenne Tribe has proposed with the help of huge incentives from the Inflation Reduction Act. Tribes typically wouldn't qualify for federal tax credits because they're sovereign nations exempt from federal income tax, but the 2022 law made the credits available as a rebate. It also bumped up rebate opportunities for clean energy projects on tribal lands and regions affected by coal closures—rebates for which the Crow and Northern Cheyenne Nations both qualify.

But for now, like in Colorado, it's largely the nonprofits that are getting projects done, led by Plenty Doors, which launched in 2018. Besides its incubator, the nonprofit also provides development help and education for entrepreneurs, offers loans, runs a day-labor program, and organizes arts markets, among many other projects.

Just down the highway, the Wyola Development Fund is establishing a racetrack at the community's rodeo grounds—a small arena and single set of bleachers on the edge of a field with views of the snow-topped Big Horns. Kabotie can already picture the scene when the relay track finally opens: horses zipping around the field, people from across this remote corner of the reservation gathered together to cheer, locals setting up food stands. The development fund brought in heavy equipment to cut the track in 2022, but a low-lying section flooded; the project is currently stalled as they figure out how to pay for a drainage system.

Kabotie is all in on other ideas to uplift the Crow economy. Her town needs a coffee shop and a gas station or an EV charging station to pull in traffic from Interstate 90. The Wyola Development Fund could rehab a run-down building, add solar panels, and turn it into townhomes. She also has her eye on an old church that could be converted into a small medical clinic. And how about a campground for travelers? She points to an open grassy area, which she imagines as a venue for powwows or dances.

But she's first pinning her hopes on the racetrack. "It's a visible, tangible thing that people can see," she says. "That's what's required to get people's image to shift. Dreams are just dreams until you wake up and put some muscle in to change your situation."

It's easy to wonder what people like Lesley Kabotie and Charlene Johnson might do with a few million extra dollars.

The Magazine of The Sierra Club

The Magazine of The Sierra Club